Jo Baker

By Sean Tuohy

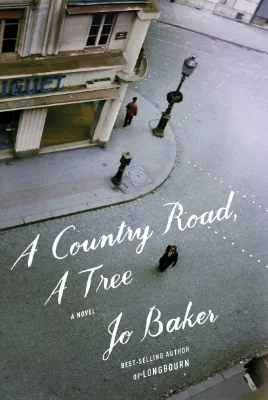

Paris, 1939. The Nazi war machine is charging into the city at the same time an unknown writer from Ireland arrives. Samuel Beckett finds himself involved with spies and a city under siege in Jo Baker's haunting new novel A County Road, A Tree.

Available for purchase today, Baker's latest book is filled with passion and crafted by a talented writer. The author was kind enough to sit down and talk about the craft of writing and how she placed herself in Paris during the beginning of World War II.

Sean Tuohy: When did you know you wanted to be a writer?

Jo Baker: I don’t think “wanted” ever really came into it. Writing was just something I did. Like snails make slime, like bees make honey. Just something instinctive and necessary. The idea of doing it professionally was only something that emerged in my mid-twenties, when I was around other people who were doing that already. But I never really “wanted to be a writer;” I just felt the need to write.

ST: What authors did you worship growing up?

JB: C.S. Lewis, Susan Cooper, Louisa May Alcott; as a teenager I loved Austen, Eliot, Steinbeck, Woolf.

ST: What is your writing process?

JB: Things hang around a long time before they become stories. One element might be acquired and wait 10 years for another element to come along and make it react and begin to fizz. I have no control over that—it’s something that happens and I just have to be open to it.

Once the thing is fizzing I just write a first draft longhand. I’ll redo bits, and then shape the whole thing as I move onto the computer, and then begin redrafting and then polishing. I only share the work at a fairly late stage, even with my first readers—early feedback can be confusing and disabling. When it’s nearly ready to be seen, I’ll read it out loud to myself, the whole thing. I try and be alert for rhythms, redundancies, that kind of thing.

ST: In your new novel, you're dealing with 1939 Paris with Germany invading and all-out war right around the corner. What kind of research did you undertake before writing the novel?

JB: I did a good deal of historical reading around the period—both of the progress of the war, and more social history. I read memoirs and fiction from the period—fiction is often brilliant for historical detail that might otherwise not be available. I also was able to use Beckett’s letters and the biographies. On a more practical level, I did a kind of “beating of the bounds” of the Parisian neighbourhoods involved in the story. You can find images online from the ‘30s and ‘40s, as well as in published histories, and it is fascinating to overlay them over the present day.

But alongside that I thought it was important to not impose a present-day understanding upon the moment. What is known on the ground at the time is not necessarily what is understood with the benefit of hindsight and a historian’s grander perspective. And I very much wanted to keep it all within the realms of the characters’ experience. I had to leave out a good deal in order to maintain that and not to overload the narrative.

ST: How did you get yourself into the mindset of 1939 Paris?

JB: I suppose that was through a process of research-plus-imagination. I spend a good deal of my time while “writing” actually sitting with my eyes closed and daydreaming myself into a world, a way of seeing someone else’s shoes. Sometimes I make faces. Sometimes I mutter. And I tend to work in a coffee shop, so that’s a bit embarrassing. So I daydream, but daydreaming is very much informed by the research.

ST: As a novelist, was it difficult to write fiction about historic events?

JB: It presents particular challenges. It’s a challenge to get things historically “correct” while also shaping an engaging and functional narrative. But the constraints can also be enabling. Those pre-existing facts set limits as to what you can and can’t do, and so you tend not to waste time; you just get on with doing what you can. When writing straight fiction you still have to make a series of decisions that set the limits of your work. When writing historical, some of these decisions have been made for you. So in a way, that helps.

ST: A Country Road, A Tree could be an espionage tale but it could also be take on the life of a young Samuel Beckett. Either way it is a gripping story. What kind of tone were you chasing when you decided to write the novel?

JB: I was hoping that the book could be read by someone who doesn’t know Beckett’s work at all, and enjoyed it as a story in its own right. And that alongside that, it could be read as a reflection too on the growth of an extraordinary writer and man, during what was a transformational period in his life.

ST: What’s next for Jo Baker?

JB: I have a couple of projects in hand; one underway, one beginning to bubble. And beyond that I have what feels like a very ambitious idea… maybe even a series… but it’s the early days.

ST: What advice would you give to first-time writers?

JB: Keep writing. Just keep writing. No one else is going to do it for you.

What matters is the work, not the getting published. Everything else follows from the work being good.

ST: What is one random fact about yourself?

JB: I can juggle.

To learn more about Jo Baker, visit her official website, like her Facebook page, or follow her on Twitter @JoBakerWriter.