By Stephanie Schaefer

Although great literature allows readers to escape, writing can also help us make sense of reality. For many, journaling is a healing process and the ability to craft your own narrative can be especially empowering. With these goals in mind, former soldier and a Foreign Service officer Ron Capps founded Veterans Writing Project (VWP), a D.C. based non-profit that helps veterans tell their stories.

The organization provides no-cost writing seminars and workshops for veterans, active and reserve service members, and military family members. They also publish a podcast and literary review that features works of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry.

Among his accomplishments, Capps has been a speaker on National Public Radio’s “All Things Considered,” PRI’s “The World,” Pacifica Radio, BBC’s “World Service” and has been a consultant to Time, Rolling Stone, and PBS “Frontline.” His writing has been featured in respected publications, including The New York Times and his memoir, Seriously Not All Right: Five Wars in Ten Years, was recently published by Schaffner Press.

Capps answered my questions about VWP, his writing process, and how the creative arts can help people recover from traumatic events.

Stephanie Schaefer: What inspired you to create Veterans Writing Project?

Ron Capps: When I left government service—I was both a soldier and a Foreign Service officer— I wanted to find a way to continue serving others, and the VWP was the vehicle I created to allow me to do so. I was coming home from a graduate school class one night and it struck me that I wanted to make sure that I was a good steward of the money I used as part of my GI Bill VA Benefits. So I developed the idea of giving away what I had learned and the VWP grew out of that.

SS: What are the goals of the organization?

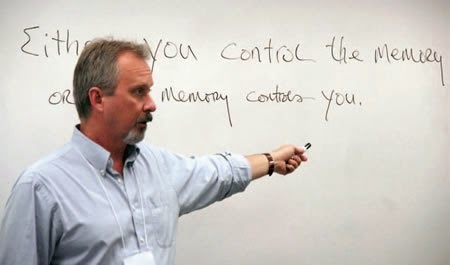

RC: We approach our work with three goals in mind. The first is literary. We believe there is a new wave of great literature coming and that much of that will be written by veterans and their families. The next is social. We have in the United States right now the smallest ever proportion of our population in service during a time of war. Less than 1% of Americans have taken part in these most recent wars. And our WWII veterans are dying off at a rate of nearly 1,000 per day. We want to put as many of these stories in front of as many readers as we can. Finally, writing is therapeutic. Returning warriors have known for centuries the healing power of narrative. We give veterans the skills they need to capture their stories and do so in an environment of mutual trust and respect.

SS: Can you tell me more about the literary journal, O-Dark-Thirty?

RC: We publish the work of veterans, service members and their adult family members across the genres of fiction, non-fiction, poetry, and plays. We have two platforms. The Report is our core publication and we try to publish something new every three days or so. It is online only.

The Review is our quarterly literary journal. It is both in print and online. We have a curatorial rather than a judgmental editorial policy. Works land where they do based on what’s going to fit well where in terms of what theme we’re chasing that quarter or what’s most recently come before on the web. We also feature art by veterans on the cover of The Review.

SS: How have veterans responded to VWP’s initiatives?

RC: I think quite well. We’ve been able to expand our reach beyond the local Washington DC area. So far we’ve been in Pennsylvania, Maryland, DC, Virginia, North Carolina, Texas, Illinois, Kentucky, Iowa, South Dakota, and Arizona. We’re able to put on seminars and workshops in the elements of craft (scene, setting dialogue, point of view, etc.) as well as genre specific workshops in fiction, non-fiction, poetry, and playwriting.

Of course, we’re also part of the National Endowment for the Arts’ programming at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. We provided the curriculum for the therapeutic writing program at Walter Reed’s National Intrepid Center of Excellence (NICoE) and teach creative writing there, too.

SS: Congratulations on publishing your memoir, Seriously Not All Right: Five Wars in Ten Years! Can you give us a brief synopsis of your work? What was your writing process like?

RC: Thank you. The book covers the period between 1996 and 2006 when I was deployed to Rwanda, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Darfur; and, as well, the period of time back in the U.S. after I was medically evacuated from Darfur following a suicide attempt and my ongoing recovery from PTSD.

The process was long. I started writing in 1999 while I was in Kosovo. As a Foreign Service officer there I was asked to write crisp, dry accounts of messy, horrible acts of cruelty—war crimes, ethnic cleansing, terrible brutality. I found out that I needed to capture more than I was doing during the day at work, so I began writing at night. Over the next 14 years, I kept writing and ended up with a memoir.

Some of the writing was done in theater—on the ground in Afghanistan, Iraq and Darfur—some was done at home afterwards. The stuff I wrote in Afghanistan was particularly messy: mostly stream of consciousness, no punctuation or line/paragraph breaks, profanity-laced. I spent a couple years in grad school at Johns Hopkins editing that as well as creating new work.

I got a few of the pieces published as stand-alone essays. One was selected for Best American Essays 2012 and one won first prize from Press 53 in their Creative Non-Fiction contest. I included those as elements of the book proposal, and in time I had a contract with Schaffner Press to produce the book. My publisher and I then spent even more time shaping the narrative and filling in gaps—think of connective tissue between major limbs—in the pieces I had already completed.

SS: Did you find that writing your memoir was therapeutic for you?

RC: I did. I used my writing as a form of therapy when medication and therapy didn’t work. I think any of the creative arts can serve as a way of helping to recover form trauma, but writing is the one that worked for me.

SS: In recent years there’s been a push for STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) education, which is essential, both in and out of the military. Do you consider writing and the ability to communicate stories with others equally as important?

RC: Yes. I’ve recently seen this acronym rendered as STEAM—science, technology, arts, engineering, and mathematics. The National Endowment for the Arts is apparently working on a number of projects with the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health to broaden the scope of teaching in the sciences and technology to include arts programming.

SS: How can other literary-enthusiasts support your cause?

RC: In plenty of ways, but I’ll list two. Send anyone you know who is interested in our work, either teaching or publishing, to us to let them see what we do and how well we do it. Second, we need sponsors to get out to do this in other places. If anyone is interested in having us come out to their school or town to teach, get in touch with us.

SS: Name one random fact about yourself.

RC: I paid my way through college as a professional musician singing in an opera company, in musical theater, and as a singer/guitarist in bars.

To learn more about Veterans Writing Project, visit its official website, like its Facebook page, or follow the group on Twitter @VeteransWriting.