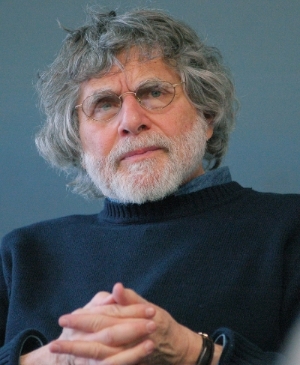

Alan Cheuse

By Daniel Ford

You may know Alan Cheuse as a commentator on National Public Radio’s “All Things Considered,” however, he’s also an author in his own right!

Throughout his career, Cheuse has published five novels, four collections of short fiction, two volumes of novellas, a memoir, and a collection of travel essays. All that and he has to find time to read all the books he reviews on the show! That’s true dedication to the craft of writing and creativity.

Cheuse’s latest work, Prayers for the Living, was published through Fig Tree Books and is “an epic family saga about the American Dream gone to pieces.” The author’s lyrical prose makes you feel like you’re at the main characters’ kitchen table, listening to this tortured family tale.

Cheuse recently answered my questions about his work with NPR, his writing process, and how he developed Prayers for the Living into a novel.

Daniel Ford: You’ve been reviewing books on “All Things Considered” since 1980. When did you first fall in love with books?

Alan Cheuse: My first encounter with a book and reading was purely visceral. My father, a native Russian speaker read to my when I was very young from a collection of Russian fairy tales, and I can still hear the shush-and-slide his Russian vowels and the clacking of the consonants, and I can still recall the scent of the book (which he had kept stored in an old trunk sent from Shanghai to his first American address somewhere in Brooklyn)—it gave off the odor of oranges under a warm sun. I never learned Russian, but became a devoted reader of sea-stories and fantastic fiction fairly early on in my primary school days. And went on became a science fiction fanatic in middle school and high school. Though I was curious about some of the books on display in the adult section of the Perth Amboy New Jersey library I frequented after school. There was a novel called Invisible Man that I picked up and read for a paragraph or so. And then I found Arthur Clarke’s work. And early in high school I found D.H. Lawrence and James Joyce in a local hole in the wall bookstore on our main street.

DF: Who were some of your early influences?

AC: The adventure novels and the science fiction opened my mind to what the imagination might create (though I couldn’t have put that into words back then). But probably James Joyce and Lawrence, and later Ernest Hemingway and Virginia Woolf.

DF: How did your training as a literary scholar help (or perhaps hinder) your first writing projects?

AC: I can only say it helped, because it made it possible for me to get a teaching post where I could devise courses filled with all the reading I needed to do in order to become the writer I am—a cycle of narratives from Gilgamesh and the Homeric epics all the way on through Chaucer and Shakespeare and Cervantes and the great English, Russian, French, and Italian novelists. And modern writers from Gertrude Stein and Sherwood Anderson and Joyce and Hemingway and Faulkner and Woolf and Cather—oh, the long, classic line.

DF: What is your writing process like? Do you listen to music? Outline?

AC: With a novel I write a draft and revise, draft and revise, and so forth over some years until an editor and my best readers (headed by my wife) say I am getting close. With a story I do the same, though the process is more luxurious, because it only takes a few weeks or a few months to complete a story. But music? No. The only writers I know who listen to music while they compose are poets. Makes me wish I were a poet!

DF: You haven’t tied yourself down to any one genre in your career, writing everything from short stories to novellas. Is that a reflection of your personality or were you just following where your stories led? And do you have a particular favorite genre?

AC: I like your image of following where the story leads. After thirty plus years of writing fiction—I started late, not publishing anything until about a month before my fortieth birthday—I think I have cultivated my instinct for knowing what material should be a story and what should become a novel. I feel lucky that I have been able to work with some modicum of success in both the short and the long forms (and the middle length of the novella as well. It’s like being able to compose etudes and sonatas and symphonies, perhaps.

DF: Where did the idea for Prayers for the Living originate?

AC: A news item in The New York Times in the early 1970s told of the suicide of a Long Island rabbi turned corporate head caught in a financial scandal. The notion of a rabbi turning into a successful businessman who became tainted in his work intrigued me.

DF: What were some of the themes you wanted to explore in Prayers for the Living and how did you go about intertwining them with the American Dream and the American Jewish experience?

AC: Some of the motifs come from tragedy—the rise and fall of a talented man with a flaw who rises high and falls far, destroying himself and his family in the process. And some come from contemporary American life, at what I see is the crossroads of American Dreaming. How can someone become both rich and blessed as a soul.

DF: What I found interesting about the structure of Prayers for the Living is that the prose reads very much like dialogue. Your characters’ speech and the prose surrounding their conversations have a lyrical quality to them, which makes the events of the novel all the more crushing at times. How did you develop that structure and did it change at all during the writing or editing process?

AC: Minnie Bloch, one of a number of characters in the first few drafts, eventually rose to become the narrator, and her voice has that distinctive mixture of the lyrical and the raw voice of experience that I first heard in the voices of my own mother and grandmother and aunts around the dinner table in New Jersey while I was growing up.

DF: You created all of these damaged characters for this novel that are reacting to their situations differently. How did you get yourself in the mindset to write each of their stories and how do you develop characters in general?

AC: You try to develop a sense of each character’s strengths and weaknesses—and a diction appropriate for each—and then bring them on stage to make music together. A novel is a drama and a concert, an opera, for which you also have to find the right musical instruments to accompany the leads, sometimes getting down to such radical necessities as inventing new instruments in order to produce certain sounds.

DF: How has your work at George Mason University and the Squaw Valley Community of Writers influenced your work?

AC: The former helps put bread on the table and the latter helps seat good people there to partake of it.

DF: We love to review novels on Writer’s Bone, so I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask you what you look for when you’re choosing books for “All Things Considered.”

AC: I want a beautifully composed work of fiction with a forcefully forward moving story inhabited by fascinating characters whose ups and downs show me things about the world and my own life I have not imagined before reading about them.

DF: What’s your advice to aspiring authors?

AC: Find a master and learn from him or her, and read deep and widely to find those in the past who can tutor you in the present.

DF: Can you name one random fact about yourself?

AC: Everything about me seems random on a bad day; nothing does on a good day. But I write every day, religious and national holidays included, except when I’m traveling. Random, random—I enjoy pushing our grandchildren on swings, very good exercise.

To learn more about Alan Cheuse, visit his official website, like his Facebook page, or follow him on Twitter @acheuse.