Megan Abbott Brings the Magic With the Release of Give Me Your Hand

Inside Emily Branham’s 12-Year Quest to Document BeBe Zahara Benet’s Rise to Drag Stardom

Books on the Subway Leaves Reading Material for Commuters in New York City

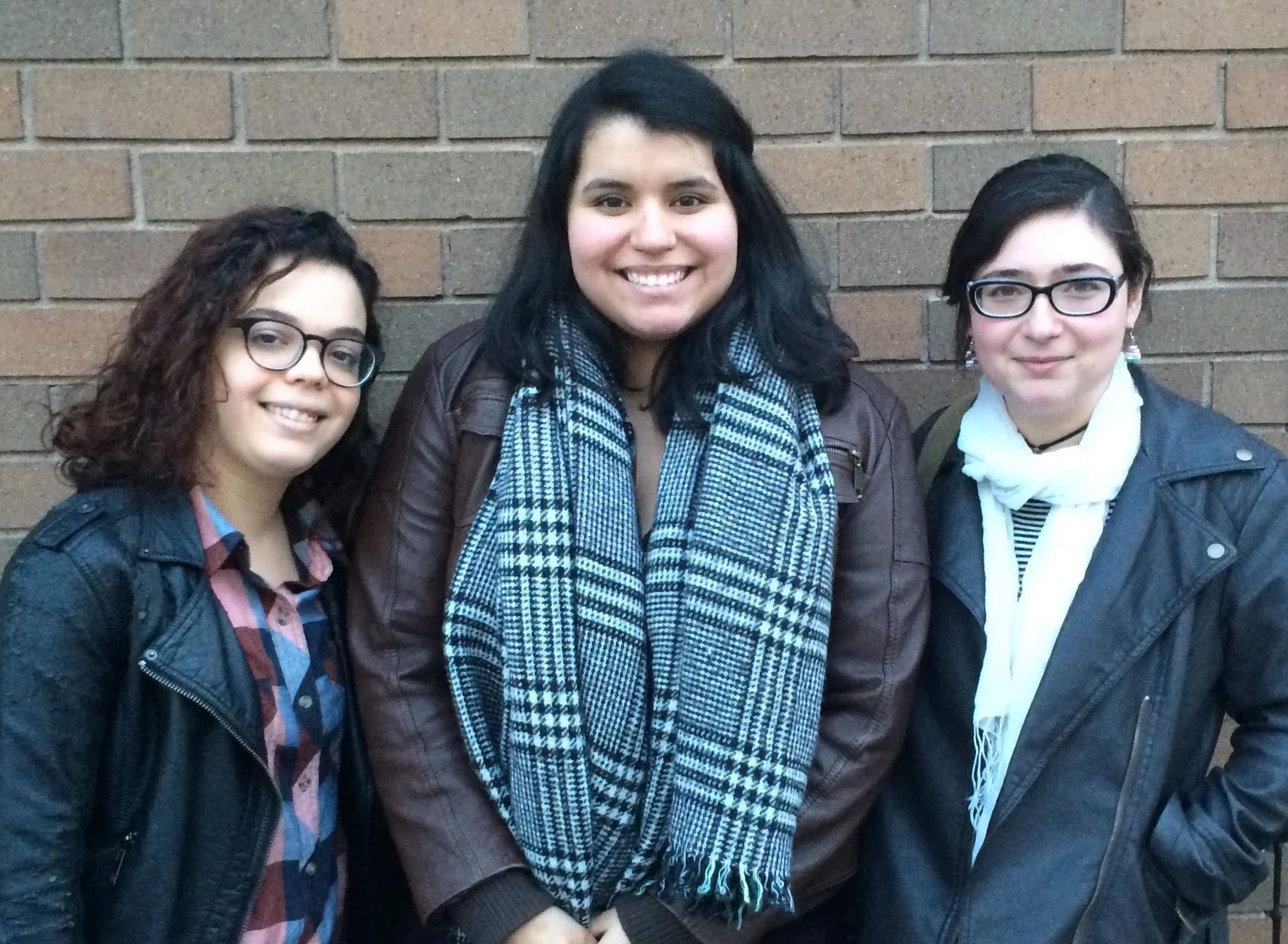

Hollie Fraser, left, and Rosy Kehdi, founders of Books on the Subway in New York City.

By Lindsey Wojcik

Rush hour had barely concluded when Rosy Kehdi swiped her Metrocard at the 23rd Street R/W subway station in New York City on a Wednesday night in early November. It was nearly 8:30 p.m., and commuters were evenly dispersed with ample breathing room from one end of the platform to the other as they waited for the train.

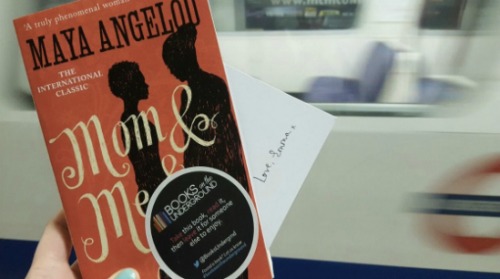

Kehdi walked through the station with purpose, her burgundy booties clicking on the tiles, to a support beam adorned with peeling blue paint, a newly-installed electronic emergency help point, and a plaque with the station’s location listed on its side. She clutched a copy of Maya Angelou’s Mom & Me & Mom in her manicured hand and lifted her smartphone in the other to capture an Instagram-worthy photo of the book with the station sign in the background. She circled the pillar a few times, snapping photos along the way in search of the perfect photo op. When she felt satisfied with the image, Kehdi walked past the station’s newsstand toward a bench at the end of the platform.

She stopped in front of an empty seat on the bench, where waiting commuters had left every other spot open between them. Balancing the book on the seat’s arm, she took several more photos on her phone as the downtown train rolled into the station. When the R train’s doors opened, Kehdi boarded, leaving the book behind on the empty bench seat.

Abandoning books on trains and platforms throughout New York City is something Kehdi has become accustomed to over the past three years. Kehdi is the founding “book fairy” of Books on the Subway (BOTS), an initiative that aims to share the joy of reading by dropping books in various New York City subway stations for people to find, read, and return back to the subway for others to enjoy.

One lucky commuter boarded the train with the copy of Mom & Me & Mom that Rosy Kehdi left at 23rd Street.

“I read a lot and I mostly read on the subway,” Kehdi says. “A lot of people read on the subway, despite what everyone says, I see a lot of people reading. [Books on the Subway] is an art project combined with a book project combined with a problem we all have, which is everyone commutes and a lot of people commute long distances. It just felt so natural for it to happen [in New York].”

Kehdi moved to New York from Lebanon in 2012. While trying to land an advertising job, she began following advertising agencies on social media. One day she came across a Facebook post from Leo Burnett, a worldwide advertising agency with offices in New York and London. The post detailed a project that one of its London employees, Hollie Fraser, had started called Books on the Underground (BOTU). “It took me 30 seconds to realize I needed to do this in New York,” Kehdi says.

She contacted Fraser, who gave her blessing and helped Kehdi design a logo and stickers to place on the book covers, which explained the concept to any confused commuters. Fraser also connected Kehdi with authors she knew would be willing to donate their books to the cause. “Hollie had been more established in London with Books on the Underground at that point,” Kehdi says. “It helped move things a lot quicker with her help. It was awesome to get her support because she is the brain behind it.”

“I definitely make sure that if I’m going somewhere I don’t normally go, I take a book with me.”

In London, Books Are All Around

Books bearing the BOTS sticker began traveling on New York City trains in 2013, a year after Fraser conceived the idea for BOTU in London, where she had lived for seven years. “I lived in East London, but started working in West London, so it was an hour’s commute to work,” Fraser says. “I started reading again and realized how much I missed reading. I kept seeing people with books and thought ‘I want to read that one.’ It felt like this community of people that would read regularly, and I thought it would be so cool if there were books you could find.”

Fraser designed the BOTU sticker and began placing books around the London tube, tweeting images of the books along with information on the locations where she left them. “I was tweeting to myself for a very long time, and then one girl found a book and she was excited, and I thought, ‘That’s it. I’ve succeeded. One person’s found a book and they love it. I’m happy,’” Fraser says.

That happiness, and the feeling of making a difference in commuters’ lives, helped propel a BOTU expansion. Fraser teamed up with authors and partnered with publishers to create campaigns that generated excitement among London’s commuters. For example, a campaign called “Love on the Underground” with Mills & Boon, a U.K.-based publisher of romance and fiction novels, gained a lot of attention. For it, Fraser temporarily changed the stickers to say “Love on the Underground,” which she placed on the publisher’s romance novels, and distributed the books during the week of Valentine’s Day. She continued doing similar campaigns, like coordinating book drops around the time when movies inspired by the prose were released in theaters.

Have you spotted a copy of A Motif Of Seasons on the London Underground today? #booksontheunderground pic.twitter.com/GIzZC9NicD

— Books Underground (@BooksUndergrnd) November 18, 2016

As the project earned media coverage and gained a following in London, it caught the attention of Cordelia Oxley. “I was brought up and around books, and read from an early age, part of that was probably because my dad has a bookshop,” Oxley says. “I always helped with displays and often with book launches too—the Harry Potter ones were probably the most exciting. When I caught a glimpse of Books on the Underground nearly four years ago, it was on Twitter, and I was so drawn to it that I contacted Hollie directly to see if I could help.”

Oxley helped Fraser grow the BOTU social media channels, in addition to helping distribute books on the tube. Fraser and Oxley worked together for a few years before Fraser and her husband moved to New York a year ago, leaving BOTU in Oxley’s hands.

“When Hollie was here, it was just the two of us who would look after the book drops, which sometimes meant dropping 100 books a day,” Oxley says. “I soon realized when Hollie left that in order to do more book drops and work with more publisher and authors, I would need some help.”

Keen on reaching every corner of London, Oxley began recruiting volunteers that she dubbed “book fairies.” In New York, Kehdi and Fraser, who have full-time advertising jobs, teamed up to drop books across the city’s boroughs. “We live in very different locations, which gets more books spread out between us,” Fraser says.

The duo pick one title per day and drop five to 20 copies during their rush hour commute, though sometimes, a longer lunch affords an opportunity to deliver that day’s book to a nearby station. They try to diversify their choice of stations, but definitely have their favorites. Fraser tends to revisit the Union Square station often, while Kehdi favors the 23rd Street R/W station. They have concentrated their efforts in Manhattan and Brooklyn, but have also made a book drop in Queens. They would also like to extend the operation to the Bronx and Staten Island in the future.

“I definitely make sure that if I’m going somewhere I don’t normally go, I take a book with me,” Fraser says. “We have occasionally done a specific location based on the book.”

The book fairies take photos of each book with hints at the location where commuters can find it in the background—usually the station’s name or a recognizable feature of the platform—and post those photos to Twitter and Instagram. New Yorkers hoping to score free reading material with a BOTS sticker on it have to be quick though. “They get picked up within five minutes at most,” Kehdi says.

Shared Book Fairies

A copy of Maya Angelou’s Mom & Me & Mom disappeared quickly when Kehdi left it at the 23rd Street station. The book, along with BOTU in London, was featured in a trending story on Facebook that day because Oxley had recruited a familiar face as a book fairy. Emma Watson chose Mom & Me & Mom as the pick of the month for her online feminist book club, Our Shared Shelf. In a partnership with BOTU, Our Shared Shelf agreed to provide copies of Angelou’s book to distribute on the London tube. Not surprisingly, Watson wanted to get in on the fun. The actress left copies of the book with personalized notes tucked inside around London, and documented her journey as a book fairy on her Instagram account.

Books on the Underground helped Emma Watson share Maya Angelou’s Mom & Me & Mom in London. (Photo courtesy of Cordelia Oxley)

The response was phenomenal. “Emma was the perfect choice [to partner with], as I had been following her book club Our Shared Shelf and seen it grow,” Oxley says. “I felt that it was a great opportunity for both BOTU and Our Shared Shelf to gain exposure but also have some fun. We took our time to plan it, and Emma was a fantastic book fairy.”

Following the success of the partnership between Our Shared Shelf and BOTU, Oxley contacted Fraser and Kehdi to extend the event to New York. “Cordelia reached out to us about Emma Watson coming to New York to drop books on the subway, and we jumped at the chance to work with her,” Fraser says. “The date happened to coincide with Election Day. It worked out perfectly because it kind of had a higher purpose to her leaving the books on the subway.”

The day after Donald Trump was elected, Watson tweeted:

Today I am going to deliver Maya Angelou books to the New York subway. Then I am going to fight even harder for all the things I believe in.

— Emma Watson (@EmmaWatson) November 9, 2016

Watson dropped 10 copies of Mom & Me & Mom around New York, while the rest of the BOTS crew delivered 30 on their own. Oxley even flew to New York to help with the distribution. “It was the first time I’d been to New York and I loved it,” Oxley says. “The subway is completely different, but quite easy to get your head around. I landed on the night of the election, and woke to the news of President-elect Trump. So it was strange to be running around frantically taking pictures of books in lots of different places, but I’m so glad it gave people a good news story.”

“It got a lot of media attention, and people were running around trying to find the books, especially the ones that Emma dropped herself, so people went wild over it,” Kehdi says. “The partnership with Emma Watson opened a lot of doors for us and exposed us to a lot of new people, so we’re hoping we can grow from there and work with more influencers.”

Emma Watson channeled her inner book fairy in New York City on Nov. 9, 2016. (Photo credit: Books on the Subway)

BOTS worked with another influencer about a week after Watson served as a book fairy in New York. On the publication day for actress Anna Kendrick’s memoir Scrappy Little Nobody, the book fairies hit the streets of New York with 100 copies, 20 of which were signed. “Anna Kendrick was in [New York] to launch her book and we knew the event had sold out, so we approached her publishers and said we thought it’d be cool if some of her fans could find the books on the subway that day,” Fraser says.

Anna Kendrick signed 20 copies of her new memoir for Books on the Subway to distribute. (Photo credit: Books on the Subway)

In London, BOTU book fairies distributed 100 unsigned copies of Scrappy Little Nobody. A packed book tour schedule did not allow Kendrick to leave the books herself, but she did tweet about it so New Yorkers and Londoners were aware that copies would be available on the trains.

“We honestly have more books in my apartment than food right now.”

Coming To A Station Near You

While celebrity fairies and authors have helped BOTS broaden its reach—its social media following has quadrupled since the beginning of November—the duo is still focused on its core values and mission. “We want to get people reading,” Kehdi says. “It’s about decreasing the barrier of getting people to read and doing something good. We never want to filter books, although we avoid religious, political or controversial ones, because we want to allow the self-published author who doesn’t have a publicist behind them to sell their books. We want to help the ones who are starting out and who just published their novel.”

“We get a lot of authors themselves saying, ‘Hey this is my first book,’” Fraser adds. “It’s very endearing and it feels so good to be able to provide that for them. No matter where the brand goes and where the market goes, we want to ensure this aspect of it is intact, and we never filter books or authors. We always want to be that grassroots project.”

Take me back to Paris! #mondayblues #booksonthesubway #paris #nyc #books pic.twitter.com/zSd6ex9KPH

— Books on the Subway (@BooksSubway) November 15, 2016

Publishers and authors interested in having a book dropped in New York can email BOTS. Fraser and Kedhi recommend including information about the book, how many books an author or publisher is interested in distributing, if they have a timeframe for the drop in mind, and any creative ideas they might have for promotional tie-ins or campaigns. Authors and publishers pay a fee to have the BOTS stickers printed, and Fraser and Kehdi cover their travel costs. “The plan isn’t to make any money from it, it’s just to basically pay for the sticker cost because stickers are surprisingly expensive,” Fraser says.

Kedhi has lost track of how many authors she’s worked with since launching BOTS, but she estimates it to be in the hundreds. Though both Kehdi and Fraser would like to have read every book they have dropped on the train, they don’t possibly have the time to do so. “I wish,” Fraser says. “I’d have to be a really quick reader.”

“We can’t possibly read them all because we do one book every day,” Kedhi adds. “We honestly have more books in my apartment than food right now.”

“I literally have a cupboard in my kitchen reserved for books,” Fraser quips.

Books may be overflowing in their apartments, but it’s clear the positive message Kedhi and Fraser champion is resonating with commuters worldwide. Similar sister projects have popped up around the globe. Books on the Metro was established in Washington, D.C. in 2014. That same year, Fraser launched Books on the L in Chicago in association with Chicago Ideas Week. The Chicago project is currently only promoted during Chicago Ideas Week, however Chicagoans have reached out, offering to run it. “It’s not a constant, year-round thing in Chicago, but it’s definitely happening,” Fraser says.

In 2016, Books on the Rail was founded in Melbourne, Australia. “So many places are receptive to this concept,” Fraser says. “We have been in talks with people in Norway, Boston, Montreal, Toronto, Delhi, and Athens about helping them set up in their cities. So watch this space.”

On a smaller scale, Kedhi says she would like to see BOTS grow its following and exposure. “I also want to see people search for the books and have it become something that all New Yorkers want to find,” she says. “We also want it to have meaning beyond just giving away books. We would like to tie it into other philanthropic causes and raise awareness on different topics where applicable.”

Fraser believes the future of BOTS is female. “I am a huge advocate of feminism, and I don’t want Books on the Subway to be all about female authors, but 85 percent of our following is women and more than 60 percent of our fairies are women,” she says. “I think we can really leverage that. I think we can make something bigger out of this and become a platform for women. I absolutely love the idea of hosting some inspirational book talks by female authors. But we’ll see. Rosy and I have lots of exciting ideas.”

Features Archive

That Night in Toronto: Saying Goodbye to The Tragically Hip’s Gordon Downie

One Place misUnderstood

The photographs accompanying this essay are from one of Appalachian photographer Roger May’s current projects,’Til I No More Can. In February 2014, May started the crowdsourced photography project, Looking At Appalachia, which works to dismantle long-held stereotypes of the region by showcasing Appalachia’s diversity through photography. For more on Roger May visit his website at www.rogermayphotography.com. To view the Looking At Appalachia project, visit www.lookingatappalachia.org.

By David Joy

When I sit down to begin a story, the canvas isn’t blank because there is already a setting. There are mountains, streams, buildings, and roads, so that when a character finally arises, that character claws himself from the ground. Because he emerges from that place, he already has a name, an accent, and mannerisms that are tied directly to the dirt from which he rose. That place for me is Jackson County, North Carolina, and it is because that’s the only place I know.

At the same time, I don’t write books about Jackson County. Nor do I write books about Appalachia. I write stories about desperation. A fellow writer and friend, Brian Panowich, says I write love stories, and while I don’t necessarily know whether that’s true, I know it’s a lot closer to the truth than to entertain the notion that my stories are snapshots of a region. I write tragedy. I write the types of stories that I like to read; stories where any hint of privilege is stripped away so that all we are left with is the bitter humanity of it, and stories about lives pinballing between extremes because there is nothing outside of sheer survival. Within those extremes, there is gut-busting laughter, heart-wrenching sadness, murderous anger, and lay-down-my life love. That, for me, is the human condition.

Yet, because of where my stories are set, I have people all the time, particularly people from outside this region, who ask how my work represents Appalachia. They ask whether the drugs and the violence that I write about are the cold reality of the place where I live, to which I always respond, “No more than right here.” I once had some ritzy media escort wheeling me around in a Mercedes through some noisy city who asked what people where I’m from thought of my work, before stuttering, “Or can they read?” If it’d been a man, I might have hit him, but she wasn’t and so I ate it. I let that feeling roil around in the pit of my stomach for a moment, then responded simply, “Yes, we can read,” then lifted my feet from her floorboard and shook my boots adding, “We even have shoes.”

If it were up to me I would never leave Jackson County from now until the day I die. That may sound like an exaggeration, but it is not. I mean it. I mean it down to my very core. I’d be happy to stay right here within these 500 square miles from this breath forward. And more than that, I can tell you where I want them to bury my body. I want them to put me in the ground above Hamburg Baptist Church on that hill that’s blanketed in phlox every spring, that hill that’s so steep the flowers blow off of graves and gather in the ditch along the road that curves around Lake Glenville, that same hill where one of my best friends is buried. Put me in the ground beside him. I’ll be fine there.

I can give you a singular image of Jackson County’s landscape. Our mountains are steep and almost every road follows water. We split the highest mountain on the Blue Ridge Parkway, Richland Balsam, which is also one of the 20 highest summits in the entire Appalachian chain, with neighboring Haywood County. We’re home to the headwaters of four rivers: the Tuckaseigee, Whitewater, Horsepasture, and the Chattooga—that being the same Chattooga that Burt Reynolds paddled in “Deliverance,” but higher, up where that river starts as a creek, not down in the hot country running the Georgia/South Carolina border. In summer, the place is eaten with green, so much of it that that one of my mentors who came to these mountains from the desert said that she felt strangled by it. In winter, the trees are stripped down to their gray bones and in that nakedness you can see the contours of the mountains, the hollers, and coves smoothed and weathered over the past 480 million years. There’s some farmland along the river bottoms, but not near as much as Haywood County to our east or Macon County to our west. The land here is too steep for the most part, a place better suited for black bear and deer, turkey, and salamanders than people.

Drawing a singular image of our people, that’s where things get difficult, or, rather, impossible. I can take you to someone whose ancestors were some of the first to settle here, people with names rooted to this place, names like Hooper, Woodring, Broom, McCall, Dillard, Rice, Messer, Mathis, Farmer, Coward, and on and on till the cows come home. I can introduce you to people who still run bear with walker hounds and Plotts, people with wild ramp patches they hold in secrecy as if those onions were as valuable as ginseng. I can take you to front porches where people still gather on Sunday afternoons to pick stringed instruments and sing old ballads and hymns they’ve memorized like recipes. At the same time, I’ve sat in a bar in town and listened to a reggae band one night and then turned around and heard world-renowned jazz guitarist Freddie Bryant grace the same tiny room the very next. Just a couple weeks back, I went and listened to a Pulitzer Prize-winner read from his work on a Thursday, then went to watch “Midget Wrestling Warriors” beat the ever-loving hell out of one another in a high school gymnasium two nights later. There are hard working people and there are deadbeats. There are god-fearing people and the godless. There are outlaws and lawmen, just as there are millionaires hitting golf balls on Tom Fazio-designed courses just over the ridgeline from people surviving off of mayonnaise sandwiches. All of this is true. All of this is within Jackson County. Come here and I will show it to you.

Spend enough time here, keep your eyes and ears open and your mouth closed, and you may come to know this place. Know this place and you will know a part of Appalachia. But you will not know Appalachia as a whole any more than I do. This is a region that stretches from the hill country of Mississippi to New York, an area covering 205,000 square miles across 420 counties in 13 states. I know people from Kentucky who will fight you for not pronouncing Appalachia the right way. “App-uh-latch-uh,” they’ll tell you. But I also know a woman born and raised in McKean County, Pennsylvania, a county just as Appalachian as Jackson, who will tell you her people say Appa-lay-sha, that her people don’t dig ramps but they do dig leeks. Jackson County, North Carolina is not the coalfields of Kentucky or West Virginia. Coal isn’t destroying our mountaintops; ours are threatened by development. What passes for mountains in the tip of Alabama would feel flat as a hoecake to someone who’d never been off the Balsams. Trying to unify this region under a singular paradigm is like trying to calculate string theory on an abacus. It’s an absurdity. I’ve lived here most of my life and I can’t.

“There are hard working people and there are deadbeats. There are god-fearing people and the godless. There are outlaws and lawmen, just as there are millionaires hitting golf balls on Tom Fazio-designed courses just over the ridgeline from people surviving off of mayonnaise sandwiches.”

As writers, we often stand painting a wall gray while people behind scream, “I love that it’s black,” or, “I hate that it’s white.” So often readers just don’t seem to get it. Recently a fan from Denmark contacted me to ask about Appalachia following an article that ran in a Danish newspaper, Berlingske, a daily with a circulation of around 100,000. The title of the May 5, 2016 article was “Helt derude, hvor de hvide, fede og fattige bor,” or what loosely translates to, “Way Out Where the White, Fat, and Poor Live.” In it, the author, Poul Hoi, used the recent Rhoden family massacre in Ohio and the novels of Daniel Woodrell and Donald Ray Pollock to argue that Appalachia is, “a heroless, malnourished, and uneducated America, where all of the goodness and normality has been sucked out to leave a tribe of murderous weirdos with rotten teeth.” The bottom line is that someone who reads Daniel Woodrell and asks about Missouri (Missouri and its Ozarks being a long way from Appalachia, though there are plenty of similarities in our people), or who reads Donald Ray Pollock and asks how that book captures the Ohioan experience, is asking the wrong questions.

These aren’t books about the South or about Appalachia. These are books about desperate people who have been backed into a corner and are left with no other option than to fight for their very survival. These are stories that, as Rick Bragg once put it, are “about living and dying and that fragile, shivering place in between.” That’s where the power of writers like Woodrell, Pollock, McCarthy, Larry Brown, William Gay, Ron Rash, and Harry Crews has always lain, and that’s not an Appalachian story or a Southern story. That’s a human story, one that could’ve just as easily been set in New York City. This is what Eudora Welty meant when she wrote, “One place understood helps us understand all places better.” Violence and drugs are certainly present in Appalachia, just as violence and drugs are present in every place I’ve ever been, but the reality is that it happens at a much less alarming rate in this region than it does in a place like Chicago where as of May 17, 2016 there had been 1,283 shooting victims since the start of the year, a year that wasn’t halfway through. These are stories about poverty and so if you want to have a conversation and you want to ask questions about what these books say about American culture, that’s one place to start.

So why are these the stories that we read time and time again out of Appalachia and the South? I think that boils down to what stories are valued by the consumer. The reason dark, violent stories are popular is the same reason newspapers as far away as Denmark are covering the recent Rhoden family massacre in rural Piketon, Ohio. As a society, we’re fascinated by violence. We eat up the sensationalism that the media feeds us day in and day out with a spoon. And this isn’t just an American phenomenon. With wide eyes and imaginations running wild, we live for these types of stories, and, for me, that says much more about human nature than it ever could about a place.

I write the types of stories I write because it’s what interests me, but even as I’m doing it I can recognize the danger. I can feel the tightrope beneath me. I told my editor recently that my biggest fear, what scares me to death, is that if readers don’t get it, if I fail, then all I’ve done is perpetuated the very stereotype people outside this region have of me. It’s one of the reasons I draw criticism from fellow Appalachian writers. But I think an artist has to work fearlessly to create anything that matters, so I put my head down and work. I write about poverty, drugs, and violence not because it's indicative of the place and region from where I come, but because those have always been the types of stories that interest me most. It’s because I think a film like Ebbe Roe Smith’s “Falling Down” or Ernest R. Dickerson and Gerard Brown’s “Juice" say a lot more about society than any romance comedy. It’s because I think writers like Larry Brown, Daniel Woodrell, and Ron Rash illuminate the deepest grooves of the human condition more than any other writers I’ve ever read.

What is at stake when a reader takes a novel, particularly a noir or a piece of literary crime fiction, as is often the case, and believes the story wholly represents a region and a people is the same perpetuation of every other stereotype. It’s listening to the rapper 50 Cent’s “Get Rich Or Die Trying” and thinking that you understand the African American experience. It’s watching a few episodes of “Will and Grace” and believing you know what it’s like to be homosexual. It’s staring blankly as a group of men fly airplanes into towers or walk into the crowded streets of Paris and open fire with automatic weapons and thinking they represent the entire Islamic faith. It’s dangerous and it’s disheartening. Misinformation and fear is what perpetuates hate.

So if you want to know what it’s like in Appalachia read broadly. Read novelists like Silas House and Lee Smith. Read Robert Gipe’s Trampoline and Crystal Wilkinson’s The Birds of Opulence. Read Jeremy Jones memoir Bearwallow: A Personal History of A Mountain Homeland. Jones, by the way, does play the banjo, but also has a full head of teeth and an absolutely wonderful smile. If you want to know about the South read writers like Jill McCorkle and George Singleton. Read All Over But The Shoutin’ by Rick Bragg. For god’s sake, read poetry! Read Wendell Berry, Maurice Manning, Jane Hicks, Darnell Arnoult, Denton Loving, Rebecca Gayle Howell, Frank X Walker, Ron Houchin, Ray McManus, and Tim Peeler. But don’t think of the people you meet in these books as Appalachian or Southern. To regionalize is so often to marginalize. Instead, see the humanity and question that rather than where they come from. Over and over, we all keep looking for differences. But now more than ever, we need to start seeing our similarities.

David Joy is the author of the Edgar Award-nominated novel Where All Light Tends To Go, as well as the novel The Weight Of This World, forthcoming from Putnam Books in early 2017. He lives in Webster, North Carolina. He’s also a newly minted member of the Writer’s Bone crew!

Features Archive

Let It Ride: A Night With The Silks

The Silks: Sam Jodrey, Tyler-James Kelly, and Jonas Parmelee

By Dave Pezza and Daniel Ford

Living in New England you grow accustomed to old things: mills from the Industrial Revolution, houses built by veterans of the Revolutionary War, cobblestone streets. While this region embraces its age, it’s not defined by it. The people and institutions in this part of the country have an enduring ability to rework and rediscover purpose from their fading history. It makes perfect sense then that a rock band named The Silks would hail from Providence, R.I., and that they’d play the rejuvenated Columbus Theatre on a stinging cold winter night.

The musky theater, built in 1926, features a simple lobby that opens to two connecting staircases. Fans of both The Silks and the evening’s headliner Patrick Sweany were led to a secondary theater set up for an intimate, urban rock show. Instead of old projectors beaming silent films to the masses, the rectangular cutouts behind the stadium seating housed spotlights that bathed the stage in red fluorescent light.

The band and the venue formed the perfect fusion of past and present. The Silks, who put out their first album in 2012, sound like the theater looks: aged, but teeming with energy. Daniel Ford and I met Jonas Parmelee—the band’s bass guitar player—and his Farrah Fawcett locks by the band’s merchandise table, which he was running on his own. He eagerly led us to the band’s front man, Tyler-James Kelly, whose hair and manic energy channeled Ted Nugent. After tracking down drummer Sam Jodrey, who looked like he crashed out of a Def Leopard music video, the band guided us through a side door that led to the Columbus’s main room.

“We have a lot of older influences, like Jerry Lee Lewis and Chuck Berry. But that’s where we started. So if you think about it, we’re only like second generation blues guys,” says Kelly, who also plays guitar.

His assessment reverberates through the band's sound, which is an energetic, honky-tonk mix of Creedence Clearwater Revival and Cream. Despite their classic rock influences, the band makes it clear the sound is all their own.

“I don’t sit down and think, ‘Oh, I’m going to write an old timey song now,’” says Kelly, who crafts the majority of the band’s music.

He settled into a seat upholstered in hard leather perched above the silent, dark theater, flanked by his band mates. The long, wooden stage, watched by a sea of empty chairs spread out under the aging balcony, was once the home of vaudeville acts that entertained scores of Rhode Islanders.

“We want to make music to make people move,” Kelly says. “We write to please. It’s your time to fucking boogie.”

Parmelee saw Kelly play a solo set at a former rock club in downtown Providence called Club 201. They started making music together, found a drummer, and recorded a proper album. The Silks drifted through a few years of on-again, off-again touring, and then their drummer quit the band.

“You know, everyone has their reasons and their priorities, no hard feelings,” Kelly says. “It’s hard living out of a van and driving all over the place.”

Kelly, a little fidgety—in truth, the rocker rarely sat still the entire evening—explained that they’re “still making music the hard way,” burdened with day jobs, long road tours in the van, and hawking their own merchandise at gigs.

The touring paid off, though, in the form of Jodrey. He joined the band almost a year ago after Parmelee and Kelly watched him play a gig in Detroit. Jodrey learned the band’s songs on the fly, sometimes in the bathroom right before a show.

“It happened so fast,” says Jodrey, “It still feels super new, but at the same time it feels like I’ve always been here.”

When asked about touring and replacing the band’s previous drummer, Jodrey put it simply, “Everyone wants to be in a band, but no one actually wants to be in a band.”

The band’s fate is far from certain, however, Jodrey seems to have invigorated The Silks. They had just wrapped principal recording on a new album, and were prepared to debut the new tracks during that night’s set.

"We were just sent the final mix of the last song,” Kelly says. “It sounds petty good."

Like a newly minted father eager to share baby pictures, Kelly dug out his smartphone to play a rough track from the record. He apologized for the crappy cell phone speakers and pushed play. The transformation of the rockers was immediate. The music—indeed, good rock ‘n’ roll worthy of moving your body to—caused the trio to pound their feet on the ground and gyrate as if the rhythm was hardwired into their nervous systems.

Kelly became somewhat cagey when asked about the band’s future, the state of rock ‘n’ roll, and how artists change once they’ve hit it big.

“Oh, we’re not trying to get bigger,” Kelly says. “I just want us to be self-sufficient and be able concentrate all our energy on making our music. Rock hasn’t gone anywhere, we’ve always been here, you know. We find stories and we go play them.”

The band claimed that they don’t write about their own problems. Everything else inspires them, including the time Kelly saw a woman in a fur coat walking in the cold and thought, “Tundra warrior princess.”

“It would probably end up sounding like a bad KISS song,” Kelly says. “But some songs are like that, and others are about that girl sitting at the end of the bar. And we all know what those songs are about.”

Later, on stage, the band appeared much more relaxed, more comfortable showing than telling, cavalier in their mission to get the crowd moving. Kelly had promised us a few mid-tempo numbers, but that the band was “just going to hit you in the face with everything else.”

The Silks in their element.

As The Silks moved through their set list with an impressive acuity, each song incorporated a slightly different element of their sound (a harmonica there, a slide guitar there), but the groove was always there, triple-dog-daring you to get out of your seat. They looked aloof and nonchalant while they performed; Parmelee bopped away on the bass like Paul McCartney during his bowl cut years, and Jodrey slammed the drums like it was the last concert he’d ever play.

The only exception occurred during one of Kelly’s solos. He was the image of musical professionalism, and his intensity simmered the energy in the small theater until the dark room started to boil over, finally exploding when Parmelee and Jodrey rejoined in boisterous continuity.

Kelly had claimed earlier that he’d “bleed for you on stage.” His words sounded overly serious and out of place during the awkward, formal chat in the darkened theater, but were eerily prescient during the show. It’s rare for a musician to turn down a free beer, or substances of any kind, but that’s exactly what Kelly did when Daniel and I offered to buy him a drink before the show.

“Nah, but thanks, man. I cut out drinking and all that stuff,” Kelly says. “Really. I’ve been focusing on the band and writing. What we’ve been talking about.”

The focus shows. The band’s new songs offer a new, but welcome, twang and folksiness to their familiar classic rock sound. New track “Let It Ride,” is as catchy as anything off their debut album “Last American Band,” but it carries an undercurrent of confidence that The Silks might have been lacking. They’ve also added an additional touring musician solely dedicated to the slide guitar. The total effect is a robust sound that knocks you off your chair.

Conversely, The Silks, deep into the set list, pulled out a slow jam called “Home” replete with harmonica, blues undertones, and a melody that warrants repeat plays. “Home” could very well be what grants The Silks the attention they deserve. It’s a track that unequivocally proves that The Silks are capable of making real, important rock music, something the airwaves consistently lack.

On Saturday, March 5, the band is returning to the Columbus Theater. New and old fans alike might just be catching the start of something rare: fresh lungs belting out an old sound. Much like the city they call home, The Silks have rekindled an old and long-mourned fire. A fire that has just begun to rage.