By Dave Pezza

Led Zeppelin reissuing its albums on vinyl may not seem like a tent pole inducing event for you, but Led Zeppelin fans across the world are currently cleaning out their underpants.

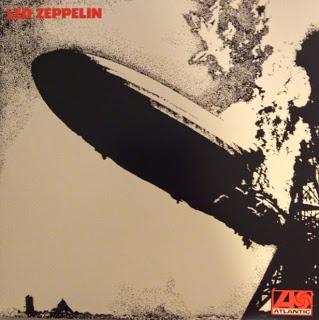

Led Zeppelin is my favorite band of all time, so posit that as you read this attempt at an impartial review. Last Tuesday, after much hype and pomp, the band reissued its first three studio albums—the newly remastered “Led Zeppelin I,” “II,” and “III”—on CD, vinyl, and digital download. The albums can also be purchased as a super deluxe, ridiculously expensive, box set with all manner of collectable gems such as a booklet, lithographs, and whatnot.

On the day of the albums’ release, I purchased “Led Zeppelin I,” the band’s freshman album from 1969, remastered on 180 gram vinyl. The album is famous for setting the band’s rock/blues foundation, the sound that immediately established them as a rock powerhouse and the faithful disciples of blues rock ‘n’ roll. It features greatest hits tracks “Good Times Bad Times,” “You Shook Me,” “Dazed and Confused,” and “How Many More Times.” I won’t waste my time reviewing the albums songs; that would be ridiculous. The remastering, however, is totally up for comment. Apparently, Zeppelin’s famed and genies guitarist, Jimmy Page, spent the last few years holed up in his mansion in England remastering the entire Led Zeppelin canon. The result is this onslaught of merchandise that is most certainly taking advantage of vinyl’s rebirth. I, however, am not complaining. I have been waiting for Zeppelin reissues since I bought my first vintage Zeppelin album.

The deluxe edition features the original remastered album on a single vinyl disc, as well as two additional discs containing an unreleased 1969 concert in Paris, France. Those of you familiar with vinyl know the always present and ignored snap, crackle, and pops. Well, Page has presented his work on some pretty heavy duty and clear vinyl. The smooth transition from outer groove to “Good Times Bad Times” is impressive. Page’s efforts become apparent in the albums’ next two songs, “Babe I’m Gonne Leave You” and “You Shook Me."

If you’re not familiar with Zeppelin, these songs immediately break the fast blues rock of the opening song, pull the barking brake on the album, and slow everything to an anguished crawl. This bluesy tandem spans a combined 13 minutes and withdraws every imaginable emotion from the human gut. On the reissue, Page meticulously sharpened every guitar note, which was expected from the band’s lead guitarist. Robert Plant, the band’s lead singer, sings a difficult range in these songs, and Page was generous with the vocals. Plant’s voice sounds little more robust than in earlier versions.

Side B opens with an arrangement by the band’s bassist and organist, John Paul Jones, titled “Your Time Is Gonna Come.” Page smooths over the song’s cacophony of electric organ into what I would consider the song’s most enjoyable incarnation. The B side’s meat, “Black Mountain Side” and “Communication Breakdown,” sound better than ever, an amalgamation of Page honing of band’s signature sounds.

“Zeppelin I" ends with “I Can’t Quite You Babe,” followed by the eight and a half minute powerhouse that is “How Many More Times.” These two songs showcase two remarkable characteristics of this reissue that make it entirely worth its nearly $50 price tag. Page has broken out John Bonham’s drum kit remarkably well. If you have even a decent sound system and listen to “How Many More Times” with your eyes closed, you can feel Bonham hit every drum in the exact position it would be if it were playing in front of you. I was floored, weak in the knees, rocked to my core. John Paul Jones’ bass track is left untouched, but this is a good thing. The best bassists play so in sync with their drummers that the bass and the drum notes slip in and out of differentiation. Page does a great job here of letting Jones’ skills speak for themselves.

Lastly, this deluxe edition contains a previously unreleased concert in Paris, France. Admittedly, you are not buying the reissues for this concert, but if you are a Zeppelin fan, it’s a nice and pleasant addition. The concert includes songs off of “Zeppelin II,” such as “Heartbreaker” and an early version of “Moby Dick.” The concert’s highlights, however, are most certainly “Dazed and Confused,” where Page breaks out the violin bow on his guitar, and a surprisingly concise and beautiful “White Summer/Black Mountain Side.”

Final verdict:

As personal tastes go, on a scale of one to five, the “Zeppelin I” reissue scores a solid 4.5. Should you spend your hard earned cash on it? Definitely. If you’re a fan, go nuts and indulge on one of the deluxe editions. But if you are not a huge fan, just pick up the original remastered album on CD or vinyl or, if you really must, digital download. You’ll be getting the best version yet of one of rock ‘n’ roll’s best albums.