Daniel Paisner

By Daniel Ford

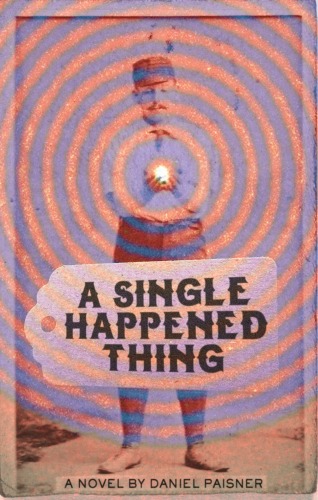

Daniel Paisner's novel A Single Happened Thing couldn't be more in my wheelhouse. The novel features a "wax-mustached nineteenth century baseball legend," a struggling creative type in the 1990s, and a Bob Dylan epigraph. Truly a trifecta sure to warm my baseball/writer heart.

The author talked to me recently about Norman Mailer’s influence on his early writing career, being a celebrity ghostwriter, and what inspired A Single Happened Thing.

Daniel Ford: Did you grow up wanting to become a writer or did the desire to write grow organically over time?

Daniel Paisner: I think what changed over time was the kind of writing I wanted to do, but those writing muscles were always there. In the beginning, I wanted to be Woodward or Bernstein. The idea of working in a newsroom, righting wrongs, chasing down stories, participating in some sort of larger conversation. It held enormous appeal. But that changed. I did start out as a reporter, but most of my early newsroom assignments were drudgery—zoning board hearings, pie-eating contests, and ribbon-cutting ceremonies. Meanwhile, I'd always written stories, and I started in on my first novel while I was still in college, so I found myself retreating into fiction more and more. Somewhere in there I found I had a knack for capturing people's voice and personalities on the page, so I started doing that too—working in collaboration with actors, athletes, politicians, and regular folks with slightly irregular lives on their memoirs and autobiographies.

DF: Who were some of your early influences?

DP: Mailer was probably the biggest influence—only not in the ways most people mean when they offer up his name in answer to such as this. I'd always admired his novels (mostly Why Are We In Vietnam? and An American Dream), but his long-form, nonfiction reporting was startling, vigorous, completely unique. And then I read The Executioner's Song, and it was so spare, so taut, and so incisive. I came away thinking I wanted to write like that. I was completely blown away. The book had the power and sweep of an epic novel, but the reader was inside the head of this flawed man, in such an intimate way. I'd never read anything like it.

DF: What’s your writing process like? Do you outline, listen to music, etc.?

DP: My process is a bit of a mish-mash. I write when I can, in what ways I can, when the book calls to me—not exactly a formula for a successful writing life. My new book was written in fits and starts over a period of several years. It started with an idea; with a character, really. And I don't think I let go of that character the entire time I was working on the piece, even if I wasn't necessarily sitting at my desk and working on the piece in a traditional sense. I was working it through in my head. Sometimes, this happened through music. There was one James McMurtry song that haunted me. There was a line in it that spoke to me of the rootlessness at the heart of the story I was trying to tell. "I'm not from here, I just live here." I played the crap out of that song. Sometimes, I found the rhythm of the piece when I was out for a long run, so I started going out for longer and longer runs. In fact, I ran a couple marathons at the front end of the book's long gestation, and those miles were like a moving writer's workshop. When I thought I had a thing or two figured out, I'd roll up my sleeves and write in bursts, sometimes through the night, until I had it down.

DF: How did you develop your voice? Are you able to slip into it during the writing process or is it something you find while you’re editing?

DP: A Single Happened Thing is a departure from my first two novels. Those books featured the same main character, so they shared a certain sensibility, a certain point of view. Here I was reaching for a different tone, so I developed the "voice" of my narrator to reflect that. I wanted the reader to feel he/she was in the hands of someone who was reasonably well read, but reasonably inexperienced and uncertain of himself as a writer. I needed his self-consciousness to come through, the feeling that he carried with him that he was being watched, judged.

The story, at bottom, is about our narrator trying to convince the people he loves of an unbelievable encounter, but when his wife dismisses the encounter as a delusion his world begins to unravel. The narrative needed to reflect that unraveling, but at the same time it needed to carry the narrator's certainty. In the book I'm working on now, there's a different voice entirely. When a reader tells me he didn't recognize me as the writer of this new book, after having read my first two novels, I take that as a great compliment. Maybe it's not meant as a compliment, but that's how I take it in. The goal for me is to find a voice that serves the story.

DF: How does one become a celebrity ghostwriter?

DP: Ah, a question for the ages. I'm asked this all the time, and every answer bumps into the Catch-22 of the trade. Nobody's about to hire you to help write his or her autobiography unless you've helped a few other folks write their autobiographies first. So how do you crack that puzzle and land your first gig? In my case, it came about with a stroke of luck and an accident of good timing. And once you do a good job with your first assignment, it can lead to another. And then another. After a while, it's like you've stepped in shit and you can't scrape it off your shoes because the work starts to follow you around. I mean this in a good way, because I've come to really enjoy the collaborative aspect of my work. I get to meet interesting people, and insert myself into their lives in such a way that I can help them write meaningfully about their own.

DF: What’s the premise of A Single Happened Thing and what inspired the novel?

DP: The book is about a Manhattan book publicist who believes he's been visited by the ghost of an old-time baseball player. It was inspired by the life (and death) of one of the forgotten greats of the game—the real old-time baseball player at the heart of the story. Fred "Sure Shot" Dunlap played in the 1880s, most notably for the 1884 St. Louis Maroons of the Union Association. For a time, Dunlap was the highest paid ballplayer in all the land, and one of the most celebrated, and yet at the time of his death he was penniless, friendless, and desperate. I stumbled across his stat lines and developed a small obsession.

Mostly I was stuck on the loneliness (the alone-ness) of Dunlap's death, and couldn't get past the disconnect between how he'd lived and how he died. (The funeral home that handled his burial had to pull strangers off the street to act as pallbearers.) And yet there wasn't a whole lot about Dunlap in the public record, other than the box scores and accounts from his time in the game, so there were a lot of holes I couldn't think how to fill.

At some point, I started to connect Dunlap's story, and the restless spirit I came to imagine had stamped his days at the end, to a more contemporary story of a middle-aged man, who perhaps hadn't accomplished everything he'd set out to accomplish in life, mired in complacency and sameness at work and grooved into routine at home.

I determined that the "contemporary" story be set in the late 1990s—a more innocent, pre-steroid era for our national pastime, and a more innocent pre-9/11 time in our shared psyche as well. I wanted my characters to dwell in a world without our most recent black clouds. I wondered how these two lost souls might connect and bounce off each other, and this became the genesis of the novel. The baseball stuff with Dunlap is historically accurate; the stuff of his life is rendered as accurately as the public record allowed; the 1998-2000 baseball stuff, also as they (mostly) happened; but everything else is the stuff of my imagination.

DF: How did you get into his mindset of both your main characters—one a struggling publicist and the other a 19th century ballplayer? How much of yourself generally ends up in your characters?

DP: I read everything I could find on Fred Dunlap. I visited the library at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. I immersed myself in newspaper clippings and box scores from the period, and read a whole bunch of novels from the turn of the last century, to get my head (and my ear!) around the language. As for the Manhattan book publicist, David Felb, who becomes unmoored on the back of his apparent delusion, well, I suppose there were some elements of my own experience laced into his back story. I think it's unavoidable for certain aspects of character to attach to the characters in your novel, certain experiences as well.

But here again, the idea is to grab at the pieces that serve the story and shed the rest. The anchor in Felb's life turns out to be his baseball-mad, tomboy-ish daughter Iona, who accepts her father's story on its face. In fact, she believes she's been visited by Dunlap as well, and as the story closes she's his tether to sanity—his only tether, really. Iona is the oldest of three Felb children. I happen to have three children as well, and what's curious is that each of them believes he/she is the inspiration for Iona, and I'm not about to disabuse any of them of that notion.

DF: What were some of the themes you wanted to explore in the novel?

DP: The book is really about legacy—what it means to matter, to leave a mark. Here you had this larger-than-life baseball player, an American icon, for a time. How is it possible for someone to live a life of such broad strokes, and to somehow leave this world without a trace? Sure, Dunlap's name lives on in the record books. He hit .412 (just about off the charts!) and scored 162 runs (also, an insane number!) during his season in the sun in 1884, but his career has lapsed into obscurity. Alongside of that, I wanted to look at my protagonist, living a life of small strokes, worried that he isn't leaving any footprints at all. How do you find a way to shine when your life has been dulled by routine or disappointment? The book is also about coming unglued in a time of uncertainty, and holding fast to the people you love, even as they seem inclined to let you go.

DF: What’s your advice to aspiring authors?

DP: Write for yourself. Hold your own attention. Keep at it, and find ways to surprise yourself as you move along. Don't worry who will publish your book, who will read your book, who will review your book. These things are out of your control. Write the book you want to read. Print it out and hold it in your hands. Marvel at what you've accomplished. Then go ahead and write another one. This right here is the most encouraging thing anyone ever said to me about my work—the essence of what it means to be called to write.

And I have it on good authority, from a wonderful creative writing teacher I had in college. His name was Alan Lebowitz, one of the world's great Melville scholars and an accomplished novelist in his own right. He was the chairman of the English Department at Tufts University. He's the one who turned me on to Norman Mailer in a full-on way. And we kept in occasional touch, for a while. I even sent him my second novel, Mourning Wood, just to hear what he had to say about it. And what he had to say was this, "Write another one." So I'm stealing from him here.

DF: Can you please name one random fact about yourself?

DP: Once, I had the thrilling opportunity to ski with Stein Erikson, the Olympic gold medalist in the giant slalom at the 1952 games in his home country of Norway. And when I say I had the opportunity to ski with him, I mean I followed him around on the mountain and worked it out so I could ride the chairlift with him a time or two. I was like a stalker, really, but I timed it just right. He was kind enough to ski with me for a couple runs, and I remember being struck by his grace, his effortless style, and the way he danced across the snow. The man was 70 years old, and he moved like no one else on the mountain (And he was fast!).

What struck me too was the way other idiots like me seemed to tail him. It's like we wanted to absorb his greatness, see it up close, and understand it in a new way. When he died this past winter in Park City, Utah at the age of 88, I was reminded of this brief encounter with this absolute legend, and it put me in mind of some of the themes of this novel. Like Fred "Sure Shot" Dunlap, Stein Erikson was a man who lit up his sport. Nobody skied like him. It was a thing of beauty, the way this man skied, and for a stretch of years no one could touch him. It's like he was invincible. And yet, unlike Dunlap, Stein Erikson lived another 60 years beyond his glory. He built a ski school, became a joyful ambassador of his sport, lent his name to one of the great ski lodges on the planet. He left a mighty set of ski tracks, to where the rest of us mere mortals could fall in behind and go through the motions and imagine what it must be like to light up the sky and move about as if we too are untouchable, invincible, even if just for a moment.

To learn more about Daniel Paisner, visit his official website or follow him on Twitter @DanielPaisner.