By Rob Masiello

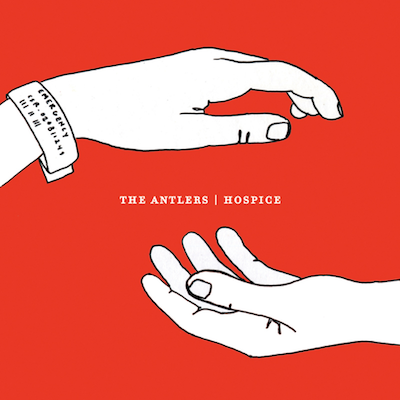

The premise is nothing short of absurd. A young hospice worker falls in love with his patient who is dying of bone cancer, and the two have a brief-but-tumultuous relationship that ends as you’d expect. This is the storyline that frames all ten tracks of The Antlers’ 2009 masterpiece “Hospice,” a concept album in the truest sense. Lead songwriter and vocalist Peter Silberman wrote the album as a metaphor for a doomed, abusive relationship, and each painstaking lyrical detail mirrors the desperation of the characters he created.

Despite the ugly images that comprise much of the storyline, the music surrounding Silberman’s poetry is staggeringly beautiful. His influences are easy to spot (Jeff Buckley, Radiohead, Neutral Milk Hotel), but the atmosphere he conjures is singular. With help from bandmates Darby Cicci and Michael Lerner, The Antlers created a world that’s both fragile and overwhelming. The suffering is palpable, but the promise of ascension never feels out of reach.

For all its meticulously narrated imagery, there are still mysteries buried within the album’s 52 minutes. The sound of a helicopter weaves in and out of certain songs, indicating imminent disaster. A track titled “Bear” seemingly describes abortion from the male’s perspective, but more likely serves as an allegory for feeling disconnected from both oneself and others (“we’re bigger strangers than we’ve ever been before / you sit in front of snowy television, suitcase on the floor”). Jarring scenes of violence intercept otherwise poetic passages, depicting characters that hurl thermometers at each other and threaten castration.

“Against all odds, the songwriting sidesteps hubris for empathy, somehow finding redemption in his flawed, selfish characters.”

More than anything else, “Hospice” is an album in the proper (and dated) sense of the term, not simply a collection of tracks. Melodies fade out, only to reappear in later moments. The lonely strum in the coda of “Atrophy” becomes a triumphant, horn-infused climax in the penultimate track “Wake,” while the lullaby-like tune of “Bear” morphs into a desolate plea in the album’s finale. That sense of continuity not only indicates thoughtful songwriting, but also reflects the album’s representation of the cycle of trauma. Silberman wrote these tracks in his very early 20s, and “Hospice” bares the kind of workmanship that only a young artist could produce, steadfast in its vision and unrelentingly insular. But against all odds, the songwriting sidesteps hubris for empathy, somehow finding redemption in his flawed, selfish characters.

With its release in 2009, “Hospice” closed out a decade of unabashedly emotional indie music. For most of the early 2000s, bands like The Arcade Fire and Death Cab for Cutie found adoration with their sentimentality and earnestness, connecting with fans across ages and genders. “Hospice” is one of the last albums of this breed, proudly wearing its bleeding heart on its sleeve. In our present era where most music—from pop, to R&B, to rock—has drifted towards coolness and kiss-offs, “Hospice” is notable for its emotional urgency. The sound isn’t warm, but it’s explosive and visceral.

At the onset of the new decade, music of this ilk fell out of critics’ favor. The success of acts like Best Coast, Real Estate, and Mac DeMarco swayed indie rock towards a slacker-rock aesthetic. Meanwhile, James Blake and The xx married the frosty minimalism of ambient music with pop songwriting, creating beautifully restrained songs that throb and swell, but never boil over. While these two strains of music could not be more different sonically, both are notable for their lack of drama. Restraint became preferred over bombast, and suddenly the music world seemed to have no room for big-hearted albums like “Hospice.”

The Antlers would never again bottle the same lightning that fueled “Hospice.” Over the course of future albums, their sound became more languid and impressionistic. Silberman found his swagger as a performer, his voice evolving from a tormented yelp into a rich croon. The turmoil that bred “Hospice” subsided, jazzy horns replaced thunderous riffs, and the band functioned more as a unit than as a vehicle for Silberman’s angst.

“Hospice” concludes with “Epilogue,” a stark and claustrophobic finale that finds our narrator haunted by guilt and resentment (“just when I think I may have fallen asleep / your face is up against mine and I’m too terrified to speak”). The horns and keyboards that decorate the rest of the album vanish, leaving a vacant hospital bed in their wake. Just as Silberman gasps his final words, the song is abruptly hijacked by a distorted electric guitar, harsh and melodically incongruent with anything that came before it. It’s a disorienting moment, akin to suddenly pulling back the shades of a dark room to let the sun pour in. Blinding white light, shattering the dank rawness of death.