Tania James (Photo courtesy of the author)

Photo credit: Melissa Stewart Photography

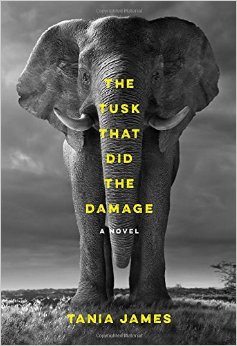

Tania James’ novel, The Tusk That Did the Damage, is both a page-turner and an emotional character study. I should say three character studies to be exact, including a broken, yet resilient, elephant named The Gravedigger.

I’ll have plenty more to say about the book in tomorrow’s book recommendation post, but in the meantime enjoy the author discuss her early influences, how she developed the idea for The Tusk That Did the Damage, and her thoughts on elephant poaching.

Daniel Ford: When did you decide you wanted to be a writer and how did you develop your voice?

Tania James: It never occurred to me that one could define herself professionally as a writer, until I met two working writers when I was sixteen. They were the poets Frank X Walker and Kelly Norman Ellis; I took their creative writing class through a summer arts camp. It also helped that they were African-American. Somehow the fact that they were minorities, like myself, gave my own point of view a sense of validity. I didn’t develop my voice back then, so much as discover that I had a yearning to develop that voice.

DF: Who were some of your early influences?

TJ: My parents and two sisters have marked my writing in ways so profound I can hardly articulate the impact, even to myself. But if we’re talking literary influences, I think of Jane Eyre as a book that opened my eyes in a certain way. That was the first book that made me wonder about the author behind it, her point of view, her intentions. I remember reading Beloved in high school and then systematically reading every Toni Morrison book I could find in the library. I’d never done that before—really delved into an author’s entire shelf. I don’t know how Morrison has influenced my own writing, but I can remember burning up with this desire to move someone else, a reader, as deeply as she moved me.

DF: What is your writing process like? Do you listen to music? Outline?

TJ: With this book, I did listen to music occasionally, just to cue me up for a certain voice I was trying to get inside. The novel moves between three different voices, so a song could help get me a particular mood. And I did draw up some outlines and timelines for the end of the book; the three threads follow different chronologies, but then interconnect around a climactic moment at the end. But I don’t sit down and outline the whole book before writing it. It’s more helpful to me to outline as I go along, so I can keep straight what I’m doing, or have just done.

DF: Where did the idea for The Tusk That Did All the Damage originate?

TJ: In 2011, my husband and I moved to Delhi for seven months. I was there on a Fulbright fellowship, and he was opening the India offices of his international NGO, Namati. He was focusing on enforcement of environmental law, and so his reading tended toward the subjects of conservation and wildlife. He kept quoting to me from a book called Rewilding the World by Caroline Fraser, in which she describes how a number of young male elephants had raped and killed rhinoceroses on South African game reserves. People in that area had never seen anything like it before. Fraser’s book led me to Dr. Gay Bradshaw’s Elephants on the Edge, in which Bradshaw suggests that this unusual aggression could be linked to post-traumatic stress in those elephants, who had themselves been victims of extreme stress when they watched, as calves, their entire herd being gunned down. As with humans, these traumas ripple outward and into adulthood.

There is something very recognizable about that wounded form of madness; you could call it human but it’s not exclusive to humans. It suggests a complicated mind at work, which is what got me interested in the subject of elephant behavior and psychology.

DF: You employ an innovative multi-narrative structure that includes an elephant (one of the most endearing characters I’ve come across this year)! What made you settle on that structure?

TJ: Thank you! I guess my interest in elephants began with those two books I mentioned, and spread to the question of human-elephant conflict. To me, the story of the elephant in India is inextricably twined with the humans who live around and amongst them, as captors and keepers, as farmers and forest guards. It’s a fascinatingly knotty subject, and to me, the most interesting way to depict that knottiness is to include two human perspectives.

DF: Despite having to service three characters, you provide a wealth of information and backstory to each one while telling an ultimately tragic story. How did you go about developing these characters, and did they change at all during the writing process?

TJ: I don’t really know my characters when they first appear in a story. They’re sketchy, even to me. It’s with every draft that I’m adding layers of detail and experience, digging away and trying to figure out who they are. It’s all kind of mysterious to me, especially when they say or do something surprising. But it’s the surprising elements that draw me in further.

DF: How has the global issue of elephant poaching changed over time, and when did you first become passionate about it?

TJ: Like many people, I’ve been troubled by the upswing in poaching, but it was through the writing of this book that I was confronted with some very stark realities. I was shocked to learn, for example, that the Unites States is currently the second biggest market for ivory imports, second only to China There was a worldwide ban on ivory passed in 1989, but it contained a great many loopholes). The recent increase in demand has fueled the ivory trade in parts of Africa, like Zimbabwe and Tanzania, where local management has a tough time keeping up with well-funded, well-armed terrorist groups. On the demand side, the United States has responded by tightening up the ivory ban; China has passed a one-year ban on ivory imports.

In India, these days, poaching elephants is less of an issue, because the tuskers (who are all male among Asian elephants) have been greatly reduced. But this reduction means a skewed male to female ratio, which means breeding rates are low. So, it’s a grim picture throughout the world. The more you learn, the harder it is to remain neutral.

DF: The reviews for The Tusk That Did All the Damage are overwhelmingly positive, including a glowing review in The New York Times Book Review. What has that experience been like and how do you manage writing and promoting your work?

TJ: That’s a good question—how to simultaneously write and promote—and one that I’d like someone to answer for me! I think it’s just harder this time around because I have a one-year old at home, so I’m trying to figure out the book/baby balance. Of course there is no balance, but I’m just trying to enjoy the moment and not get too antsy to start something new until genuine inspiration strikes. I’m keeping my ear to the ground though.

DF: You now have two novels and a short-story collection under your belt, so what’s next?

TJ: I don’t know, which is kind of an exciting and nerve-wracking answer.

DF: What advice do you have for up-and-coming writers?

TJ: I have a handful of reader friends whose advice I rely on heavily, even when it’s tough love time. I think it’s important to find those writerly mates who have your back, as you have theirs.

DF: What is one random fact about yourself?

TJ: When I was seven, I played Mary in our church nativity scene but my little sister crawled into the manger, thereby busting through the fourth wall and ruining my stage debut.

To learn more about Tania James, visit her official website, like her Facebook page, or follow her on Twitter @taniajam.