Dark and Brutal: The Inner Code of Nick Kolakowski’s Boise Longpig Hunting Club

Write the World You Want: America for Beginners Author Leah Franqui

Dissecting A Decade-Long Writing Process With The Incendiaries Author R.O. Kwon

Author Rosalie Knecht Reimagines the Spy Game With Who Is Vera Kelly?

Match Made in Manhattan: 9 Questions With Playing With Matches Author Hannah Orenstein

10 Questions With The Book of M Author Peng Shepherd

Silver Girl Author Leslie Pietrzyk on Sparking Literary Bonfires

Writing the Story With Zebulon Harris: Teen Medium Author A.M. Wheeler

By Sean Tuohy

Combining teenage angst with the ability to talk to a dead author, A.M. Wheeler’s Zebulon Harris: Teen Medium is a wildly entertaining novel.

The hardworking author and screenwriter swung by Writer’s Bone to talk about her writing process, who she based her teenage medium off of, and what’s next for her.

Sean Tuohy: When did you know you wanted to be a storyteller?

A.M. Wheeler: I started telling stories to my family around the dinner table when I was about 3 years old. I just have always been fascinated with stories and making up characters or scenarios that would make people laugh. So, I’d say around middle school, I kind of knew I wanted to work as a writer and possibly even direct film one day.

ST: What is your writing process? Do outline?

AW: My writing process is interesting. I don’t write everyday. I actually like to take some months off and experience different events, people, cultures, and then after think about my next story. I find allowing my thoughts to manifest for a while, makes my stories feel unforced and it’s my way of avoiding writer’s block.

I always outline! Before I begin writing a story, I always know the ending of the story before I even know how it begins! I find this technique best for me because if I know where a character ends up, I can then feel like a detective as I write backwards and leave little foreshadowing moments on how the characters ended up where they did.

ST: Where did the idea for Zebulon Harris: Teen Medium come from?

AW: Growing up I’ve always been interested in the supernatural world and the ultimate question of what happens after one dies. I knew I wanted to have a teen protagonist because high school was such a pivotal moment in my life. High school can be such a rough transition and once I knew I wanted to combine the world of high school with a supernatural twist, Zebulon Harris: Teen Medium, was born! I always find coming of age stories to be timeless and the ultimate of message really is universal to everyone.

ST: Zebulon “Zeb” Harris is a great main character. Unlike most characters he rejects his special abilities and sees them as a burden. Where did he come from?

AW: I think most teens in high school reject their situation or identity at one point or another. You know, if you’re tall you wish you were short; if you have curly hair, you wish it were straight. The concept of wanting what you can’t have is a struggle I really related to in high school. So, once I knew I wanted to write about the supernatural world and was trying to create this relatable protagonist, Zeb, I realized making him reject who he is would be what can connect teens to this book. You don’t have to have powers to understand Zeb’s struggle. I think readers can appreciate the concept of trying to discover yourself and accept yourself for who you are.

ST: Is there any of you in Zeb?

AW: I think Zeb is a lot cooler than myself! However, definitely his closeness to his family is something I think is similar to own life. I also think his sometimes sarcastic nature was exactly how I was in high school. He tended to not really care about school that much, and for a while I was the same way! It wasn’t until my junior year of high school that I started taking school more seriously. Otherwise, Zeb is actually more like my best friend from high school. A lot of Zeb’s mannerisms mimic his, and I think that’s why Zeb feels authentic. He’s actually partially based on a real person.

ST: What's next for you?

AW: I currently teach screenwriting and creative writing courses at a university. I have taken some time off from writing. However, I do have a few ideas for some scripts in the future, and I definitely think I’ll get back into the film festival scene starting after the 2018 New Year. I’m hoping to eventually get involved in some film shorts and possibly even end up behind the camera.

ST: What advice do you have for aspiring authors?

AW: The best advice I can give other writers is to stop overthinking before you write. Just write the story. It’s okay if the plot has inconsistencies, or the story doesn’t make total sense when you reread it. Editing will always be there, and rewriting. But, you can’t do anything if you stop yourself from getting anything on the page. Lastly, don’t take criticism personally. You may hear “no” way more times than you hear “yes," but don’t stop writing. Your writing can make a difference.

ST: Can you please tell us one random fact about yourself?

AW: One random fact about me would be that when I get to a part of a story where the character is going through an extreme emotion of anger, or being in love, or sad, I listen to music that correlates that emotional state. Music helps relax my mind and makes me feel what the character may be going through. So, usually I’ll have my headphones on and I just allow the music to make me feel certain emotions before I begin writing. I find this is the closest way to be as authentic in the moment as possible, especially when writing a piece from a first person narrative.

To learn more about A.M. Wheeler, follow her on Twitter @amwheeler90.

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

Live Deeply: 9 Questions With Snow Author Mike Bond

By Sean Tuohy

Three hunters stumble onto a crashed plane filled with cocaine in the Montana wilderness.

That’s the premise of acclaimed author Mike Bond’s latest thriller, Snow.

Bond recently took a few minutes out of his day to sit and chat with me about the new book and his advice for aspiring writers.

Sean Tuohy: When did you know you wanted to be a storyteller?

Mike Bond: By the time I was 10 I was writing poems and thinking of stories. To the young the world is magical and full of stories. All you have to do is write them down.

ST: What authors did you worship growing up?

MB: I never worshipped anyone, but I read everything, especially Hemingway, Edna Ferber, Jane Austen, the Brontës, Walter Scott, Jack London, Willa Cather, Poe, Camus, Sartre, St. Exupéry, Tolstoy, and many others.

ST: What is your writing process like? Do you outline or just vomit a first draft?

MB: I tend to write each book differently. Most I just pick up at the first sentence and write a lot of it without an outline. Or I outline only the next several chapters as I go along.

ST: What inspired Snow?

MB: I was bowhunting with a friend on a two-week horse trip back into the Montana wilderness. The constant snow and frigid conditions, plus several unpleasant encounters with grizzly bears, started the process.

ST: Snow follows four characters, but the breakout is a former NFL player named Zack. Where did this character come from?

MB: I played a lot of football, tried to make it into the NFL, but like so many football players I got so repeatedly injured that there was no way. I love playing football but have no use for watching it on the idiot box. (That’s the difference between living and being entertained.) I know a lot about the game and have a lot of friends who’ve played it, and I wanted to show it as it really is. Zack is the average football star today—multiple lifelong injuries, traumatic brain damage, constant pain, atavistic impulses, and lots of painkillers and other drugs.

ST: Snow is an edge-of-your-seat thriller but it has a fantastic human element to it as well. When writing, do you focus more on the character or the plot?

MB: I just tell the story as it is told to me. Often I can’t tell it right and have to keep rewriting it till the drama I’m seeing in my head is correctly depicted on the page.

ST: What’s next for Mike Bond?

MB: I’m finishing a 1,000-page epic on the 1960s, due out next year. And finishing the third in my Pono Hawkins series, also due out next year. This one is set in Tahiti and Paris.

ST: What advice do you give to young writers?

MB:

- Live deeply or you won’t have much to write about.

- Writing is developed from experience—from many places, lifestyles, experiences, relationships, dangers, fears and great joys. Write about that.

- Don’t write about what you don’t know about or haven’t lived through.

- Avoid creative writing classes, writing clubs, and any other collective self-reassuring groupthink.

- Don’t ever tell people what you’re writing about till it’s done, or you can kill the deep subconscious affinity between yourself and it.

- Expect to write a million words before you begin to get the hang of it.

- It’s very difficult these days to get published. But writing daily is a very good way to “Know Thyself” as they used to say at Delphi.

- Don’t expect too much of yourself. If the writing is fun, keep going. If it’s not, stop. If it’s boring to you it will be boring to the reader too.

ST: Can you please tell us one random fact about yourself?

MB: I love wild animals, wilderness, women, booze, fast cars, mountain climbing, and risk.

To learn more about Mike Bond, visit his official website, like his Facebook page, or follow him on Twitter @MikeBondBooks.

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

Dedication and Discipline: Sing, Unburied, Sing Author Jesmyn Ward On Writing

Jesmyn Ward (Photo credit: Beowulf Sheeha)

By Adam Vitcavage

Jesmyn Ward is the only author I think about on a weekly basis. Her stellar Salvage the Bones is the only novel I recommend to nearly everyone looking for a new book. If I don’t murmur the words, “Jesmyn Ward’s Salvage the Bones,” in any given week, then I at least think about how much her bleak and beautiful novel punched me in the stomach while simultaneously uplifting my spirits. Now, there’s a new novel from her I can suggest: Sing, Unburied, Sing.

I recently interviewed Ward, and I felt aspiring writers and readers of Writer’s Bone might find her comments about her writing process both encouraging and educational.

Adam Vitcavage: What excites you in the undergraduate writers you teach at Tulane University?

Jesmyn Ward: The writers who take my courses write across multiple genres. Some are writing YA, fantasy, or surreal literary novels. It just depends on the student. I love it all. What really attracts me to my students work and what makes me appreciate them is the passion that they have. I think that comes out in the work even if the work is not that polished or developed as it could be. That’s what I’m there for. I’m there to help them develop and polish it. Their passion for writing, telling stories, and creating worlds is what attracts me to their work.

AV: Once you get going with a draft for a novel, do you have a set writing process?

JW: I am a very linear writer. I work from the beginning to the end. I start at the first chapter and end at the last chapter. I don’t revise as I’m going because I feel if I stop to revise the things that I’ve written that I will get bogged down and will never complete the book. So I don’t revise and I just write straight through. I try to write for at least two hours a day for five days a week. Sometimes that is easier. I have two children, so when I have child support for them or when they’re in school is when it’s easier for me to do that. Sometimes I have to patch those hours together. I’ll wake up early and work for an hour then work for an hour later in the day when I have time.

I feel like the more disciplined I am about writing for two hours a day five days a week then the easier it is for me to access my creativity. I think it takes less time to sink into the world and to do the writing I need to do when it’s something I do five days a week. That’s how you write a book: it’s something you work at every day pretty regularly for at least a year if not a year and a half or two years. And that’s considered fast. I know some people take a decade on a book. I understand why.

It’s all about hours of dedication and discipline.

AV: Once you get the draft done, what does your revision process look like? What do you look for?

JW: The way that I revise is a little weird. I finish the first draft and then I let it sit for a month. I’ll work on other small things during that time and then I go back. I’ll read through the rough draft. Just read and take notes about things that need to be revised, changes that need to be made, things that can be cut or moved around, or whatever. I make a list and go through that list. I’ll concentrate on one thing on the list while reading through the draft. I devote an entire revision to just one aspect or one correction.

If I need to develop a character, then I’ll go through and develop a character throughout a revision. I’ll cross it off the list and go back again to concentrate on another aspect. My list can have 12 or 13 items on it. That list is just things I’ve noticed. If I went into a revision with the aim of correcting all thirteen of those things I feel I would miss something. It’s easier for me to focus on one thing through a revision. I revise twelve or thirteen times before I feel confident enough to show my work to a group of first readers.

First readers are just people that I’ve gone to school with, other writers I met at Stanford or Michigan. I’ll email them a draft and ask for their help. After a couple of months, they’ll give me suggestions and I’ll go back in and revise based on their feedback. That might take six or eight revisions. Once I’ve done that I feel confident enough that I won’t embarrass myself and I’ll send it to my editor.

And then [laughs] we revise for months. I mean, it is definitely a process. I’m the kind of writer who feels nothing is ever perfect when it’s fresh. The first rough draft is never perfect. I actually enjoy revision because writing that first rough draft is difficult. It’s different work because you’re creating this world and characters from nothing. It takes a different literary muscle than going back in and revising.

Revising is more enjoyable and more fun for me. I already have something, so at least I have the security of knowing I have something to work with on the page. Then it’s all about shaping. I enjoy knowing the security of just having to focus on making something better.

To learn more about Jesmyn Ward, follow her on Twitter @jesmimi. Read more of Adam Vitcavage’s work on his official website, or follow him on Twitter @vitcavage. Also check out Adam's full interview with Jesmyn Ward on The Millions.

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

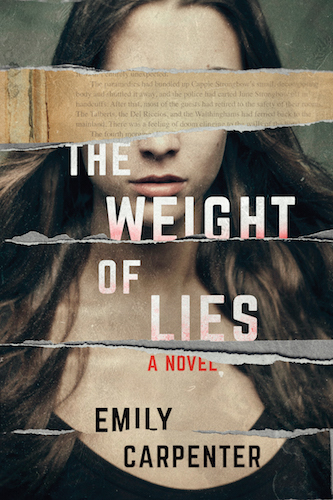

Worth the Weight: 11 Questions With Author Emily Carpenter

Emily Carpenter

By Lindsey Wojcik

The heat is on. By now, most of the country has experienced the familiar stickiness that comes with the summer season. The humidity has undoubtedly driven many to the beach or pool to cool off, and here at Writer’s Bone, no beach bag is complete without a sizzling new novel.

Emily Carpenter’s The Weight of Lies has all the makings of a classic beach companion. Vulture highlighted it as “an early entry in the beach-thriller sweepstakes.”

In her new book, Carpenter transports readers from New York City to a small, humid island off the coast of Georgia where Megan Ashley, the daughter of an acclaimed novelist, travels to discover more about her mother’s famous book, Kitten, for a tell-all memoir she has agreed to write. Kitten tells the tale of an island murder that fans believe may have been loosely based on a real crime. As the truth about where Megan’s mother, Frances Ashley, found the story for her infamous novel unravels, Megan must decide what is real and what is fiction.

Carpenter recently spent some time answering questions about transitioning from a career in television to writing novels, what inspired The Weight of Lies, and why it’s important for writers to appreciate their “customers.”

Lindsey Wojcik: You've been writing since a young age. What are your earliest memories with writing? What enticed you about storytelling?

Emily Carpenter: I’ve told this story a few times—the one about how I plagiarized The Pokey Little Puppy when I was 5. It’s my secret shame. I basically copied it word for word and illustrated it with crayons. I am not sure I actually finished it, so maybe I’m off the hook? After that, there were a couple of false starts on a novel about a girl with a horse when I was around 14. I’m not sure I had a handle on a coherent story, but I was definitely enamored by the idea of a girl (me) owning a horse. I absolutely lived for reading. I was an introvert, bookworm, a dreamer, and really imaginative. And while I didn’t really have a reference point for becoming an author, I was drawn to the whole world of storytelling.

LW: Who were your early influences and who continues to influence you?

EC: I read all of the Nancy Drew books, The Bobbsey Twins, The Hardy Boys multiple times over. Beverly Cleary and Laura Ingalls Wilder were early favorites. I loved those biography books with the orange covers, and there was another series where I remember reading about Madame Curie and Helen Keller. I read a lot of suspense books now because that’s the genre I write, but I enjoy all kinds of fiction. I’ve gone through periods when I read YA and literary classics, romance and horror. I’m really inspired by television writers right now. Noah Hawley, who writes “Fargo,” is immensely brilliant and funny. I also admire Ray McKinnon, a fellow Georgian, who wrote “Rectify.” Both those guys really inspire me.

LW: Tell us a little bit about your experience at CBS television’s Daytime Drama division. What did you do in that department? How did it influence your writing?

EC: I was the assistant to the director of daytime drama, so I basically answered phones, did paperwork, that kind of thing. I also read all the scripts for upcoming shows and wrote summaries for the newspapers to publish. I got to take contest winners on tours of the productions and assist with a couple of promo tapings of commercials for the shows. Once I took a bunch of contest winners and some of the actors to lunch because my boss couldn’t do it. I had the company credit card and had to pay for the whole thing, and it made me really nervous. I was, like 24, or something, and I’d never seen a check for a meal that big. In terms of influencing my writing, I think I really soaked up the concept of how to write tension and cliffhangers. “Guiding Light” and “As the World Turns” had some really talented writers on staff who were great at writing really funny, snappy banter, and I picked up on that—the rhythm of dialogue is so important and they were such masters at it.

I remember something my boss told me once when the writers had brought in a secondary character who was a part of this new storyline. So one Friday at the end of the show, they ended the final scene with a close up on his face. She got so mad about it and said, “You don’t end a really important scene—especially a Friday cliffhanger scene—on a day player!” She understood that, bottom line, the audience cared most about the core characters of the show. They loved them, not this random guy they’d brought in to be a temporary part of this new storyline. She knew that the show needed to leave the audience anticipating, thinking about those core characters all weekend long until Monday rolled around—not this day player. That really stuck with me, how important it was to understand who your audience was and what they wanted and giving it to them.

LW: You assisted on the production of “As the World Turns” and “Guiding Light.” Both of those soaps were on daily in my household growing up—three generations of women in my family, including myself, watched both shows, which are no longer on the air, and soap operas in general have been on the decline. What do you think influenced the change in daytime television?

EC: First of all, let me say, thank you for watching. I have a deep admiration and enduring fondness for those two shows. I watched them long after I left New York and moved back down South, and when they were cancelled, I cried. It really was such an end to an era. Although I’m sure there is an answer for why daytime TV changed, I’m not sure I know. I think, in the end, it’s probably to do with money, like everything else. And new technology and our capability to access streaming shows and binge watch really high quality programming. There’s no more appointment TV. We really have gotten out of the habit of showing up at a certain time to watch a show. I suppose the decline started with cable and cheap reality programming and TiVo. But I’m not sure what the deathblow was. And look, we still have four soaps running. I turned on “Days of Our Lives” the other day, and Patch and Kayla have not aged a whit since I watched them in the late ’80s.

LW: Tell us a little bit about your experience with screenwriting. What influenced your decision to change career paths from film production and screenwriting to writing novels?

EC: I was pretty naïve, hoping to break into the screenwriting business with zero entertainment connections or really any knowledge of the business at all. I think I had a good sense of story and structure in a general sense—I had some raw materials—but in terms of writing a kickass commercial feature, I wasn’t there. I didn’t know how to do it. And I think I was really sort of just learning the technique of writing as well. Learning how to write good sentences and evoking emotion with my words. I hadn’t majored in creative writing in school or even taken a single writing course in my life, I was just winging it. So really, it was audacious of me (or plain, old ignorant) to think I was going to write a spec screenplay that would sell to Hollywood.

But I just loved movies so much and writing and kept plugging away at it. I worked really hard and placed in a few contests, but ultimately couldn’t get an agent interested. After working on two indie productions with friends, I finally decided it was not going to happen. I took a break for a few years and hung out with my kids, enjoyed being a mom. Then one day, it suddenly occurred to me that there was this whole world of storytelling that I had overlooked. I started mulling over the idea of writing a book and researching the business side of publishing. It turned out to be much more accessible world. And I’ll say that my screenwriting experience, self-taught though it was, has formed the basis of my novel writing. I use a lot of the outlining and scene structuring tools that screenwriters use in my books.

LW: How did the Atlanta Writers Club guide you as a writer?

EC: They provided amazing access to a whole community of local writers, some of whom have become critique partners and dear friends. I found a critique group through them, which was where I read something I’d written out loud for the first time. And I attended several conferences the club sponsored and pitched my books to agents. I actually met my agent at one of the conferences.

LW: What inspired The Weight of Lies?

EC: I love classic horror books and films—Stephen King is just the master, of course. Carrie is one of my all-time favorites. One time I read that he had based aspects of Carrie on this girl he knew in school who was awkward and bullied by the other kids. That fascinated me, and I wondered if she ever found out what he did, what she would think of it. I mean, can you imagine? I get asked that question a lot, as an author, is my book based on real events or real characters? My books aren’t, but it intrigued me to imagine a writer who had the audacity to base her novel on a real murder and maybe even a real murderer, and so now there’s this eternal question out there among her fans about whether it was real.

LW: When you were writing The Weight of Lies, was there something in particular you were trying to connect with or find?

EC: Well, at the heart of the book, it’s really a story of this young woman who doesn’t feel like her mother has ever loved her or really even wanted her. And she’s so angry because she’s desperate to be affirmed and loved. She’s also a bit lost because she doesn’t have a whole lot going on career-wise, she hasn’t really been successful in the romantic department, and she’s getting older. She’s got a lot of resentment toward her mother to work through, but she’s really blinded by her pain. And her mother really is a monumentally self-centered diva, so there’s plenty of blame on both sides. That whole situation felt really compelling to me, that search to try to understand your mother as more than just the figure you rebelled against or had conflict with. Where you reach a crossroads at which point you have to decide whether you’re going to give your mother the benefit of the doubt and forgive her, or feed your childhood bitterness and hurt and go for the scorched earth option. Needless to say, Meg opts for earth scorching.

LW: How was the process of writing The Weight of Lies different from writing your debut Burying the Honeysuckle Girls?

EC: With Honeysuckle Girls, I had a lot of time. A lot of freedom. I was 100 percent on my own timetable. Then, once I signed with my agent and went on submission, it became a process of listening to my agent’s opinions and the opinions of the marketplace and deciding what to pay attention to and what to bypass. The great thing was that I had a lot of time to tinker with the book, which is a luxury. It wasn’t that much different writing The Weight of Lies because I didn’t sell the book until I had completed it. My next books, though, were sold on pitch, so that’s been an entirely new process, to deliver something you’ve already been paid for.

LW: What’s next for you?

EC: I’m writing my next book, which is about a young woman with a secret she’s kept since her childhood, who agrees to accompany her husband to an exclusive couples therapy retreat up in the mountains of north Georgia so he can get help for the nightmares that have been plaguing him. And then things start to go sideways, and she realizes that nothing at this isolated place is as it seems.

LW: What’s best advice you’ve ever received and what’s your advice for up-and-coming writers?

EC: My agent told me once, “Remember, this is your career…” I can’t even recall what we were talking about exactly—it might’ve been a deadline, or what I was going to write next—but the point was, she wanted me to clear away all the noise from other people’s expectations and do what was best for me. To follow my heart. It was just what I needed to hear at the moment, especially because I have the tendency to go overboard to make other people happy and overlook what’s in my own heart. It really settled me down and gave me the confidence to go forward.

I think one of the things I’d like to remind up-and-coming writers is that they are getting into a business and many of the decisions that editors and publishers make have to do with money. So when new writers encounter perplexing situations, I think they need to understand that financial bottom line motivates many of them. It’s sometimes a bitter pill to swallow, but it’s reality. And as writers, we have to be able to nurture our art in that atmosphere of commercialism.

The other day I heard Harrison Ford say in an interview that he doesn’t like to call people who see his movies “fans,” but “customers.” It was a really pragmatic, non-romantic way for an actor or artist to view what they do, but it did sort of speak to me because I tend to lean toward being really practical. I do see the artistic side of writing, and I can get really swept up in the magic of creating characters and a story. On the flip side, I also do really appreciate my “customers,” and I consider it an honor to have the opportunity to entertain them. And I think what the customers wants and expects should matter to writers. It’s not the end-all, be-all, but it is something to keep in mind.

To learn more about Emily Carpenter, visit her official website, like her Facebook page, or follow her on Twitter @EmilyDCarpenter.

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

Giving Back to the Universe: 8 Questions With Fantasy Author Mackenzie Flohr

Exploring the Human Animal With Crime Fiction Novelist Nick Kolakowski

Nick Kolakowski

By Sean Tuohy

Author Nick Kolakowski loves crime fiction. From his work with ThugLit, Crime Syndicate Magazine, and his upcoming novel A Brutal Bunch of Heartbroken Saps (out May 12), it’s easy to tell that the author truly values the hardboiled crime-fiction genre and knows how to write it well.

Kolakowski sat down with me recently to talk about his love for the genre, the seed that created the storyline for his new novel, and “gonzo noir.”

Sean Tuohy: What authors did you worship growing up?

Nick Kolakowski: I always had an affinity for old-school noir authors, particularly Raymond Chandler and Jim Thompson. What I think a lot of crime-fiction aficionados tend to forget is that a lot of the pulp of bygone eras really wasn’t very good: it was all blowsy dames and big guns and writing so rough it made Mickey Spillane look like Shakespeare. But writers like Chandler and Thompson emerged from that overheated milieu like diamonds; even at their worst, they offered some hard truth and clean writing.

ST: What attracts you to crime fiction, both as a reader and a writer?

NK: I feel that crime fiction is a real exploration of the human animal. You want to explore relationships, pick up whatever literary tome is topping the best-seller lists at the moment. You want a peek at the beast that lives in us, crack open a crime novel. As a reader, it’s exciting to get in touch with that beast through the relatively safe confines of paper and ink. As a writer, it’s good to let that beast run for a bit; I always sleep better after I’ve churned out a lot of good pages.

ST: What is the status of indie crime fiction now?

NK: I’d like to think that indie crime fiction is having a bit of a moment. A lot of indie presses are doing great work, and highlighting authors who might not have gotten a platform otherwise. Crime fiction remains one of the more popular genres overall, and I’m hopeful that what these indie authors are producing will help fuel its direction for the next several years.

Not a whole lot of authors are getting rich off any of this, but writing isn’t exactly a lucrative profession. There’s a reason why all the novelists I know, even the best-selling ones, keep their day jobs. We’re all in it for the love.

ST: What is your writing process? Do you outline or vomit a first draft?

NK: I keep notebooks. Over the years, those notebooks accumulate fragments: sometimes a line of two I’ve overheard on the subway, but sometimes several pages of story. Usually my novels and short stories start with a kernel of an idea, and I start writing as fast as I can; and as I start building up a serious word count, I begin throwing in those notebook fragments that seem to work best with the scene at the moment. It’s a haphazard way of producing a first draft, and it usually means I’m stuck in rewrite hell for a little while afterward as I try to smooth everything out, but it does result in finished manuscripts.

I simply can’t do outlines. I’ve tried. But outlining has always felt very paint-by-numbers to me; once I have the outline in hand, I’m less enthused about actually writing. But I know a lot of other writers who can’t work without everything outlined in detail beforehand.

ST: Where did the idea for A Brutal Bunch of Heartbroken Saps come from?

NK: A long time ago, I was in rural Oklahoma for a magazine story I was writing. It was early February, and the land was gray and stark. Near the Arkansas border, I saw a Biblical pillar of black smoke rising in the distance; as I drove closer, I saw a huge fire burning through a distant forest. This would be a really crappy place for my car to die, I thought. It would suck to be trapped here.

So that real-life scene rattled around in my head for years. Eventually I began depositing other figures in that landscape—Bill, the elegant hustler, based off a couple of actual people I know; an Elvis-loving assassin; crooked cops—to see how they interacted with each other. The result was funny and bleak enough, I thought, to commit to full-time writing.

ST: You referred to A Brutal Bunch of Heartbroken Saps as “gonzo noir.” Can you dive into that term?

NK: I love crime fiction, but a lot of it is too serious. That seems like an odd thing to say about a genre concerned with heavy topics like murder and misery, but more than a few novels tend to veer into excessive navel-gazing about the human condition. As if injecting an excessive amount of ponderousness will make the authors feel better about devoting so many pages to chases and gunfire.

But real-life mayhem and misery, as awful as it can be, also comes with a certain degree of hilarity. You can’t believe this dude with a knife in his eye is still prattling on about football! A reality television star might dictate whether we end up in a thermonuclear war! And so on. With gonzo noir, I’m trying to blend as much black humor as appropriate into the plot; otherwise it all becomes too leaden.

ST: Your main character, street-smart hustler Bill, is on the run from an assassin and finds himself in the deadly hands of some crazed town folks. Why do writers, especially in the crime fiction genre, like to torture their characters so much?

NK: Raymond Chandler once said something like: “If your plot is flagging, have a man come in with a gun.” I think a lot of current crime-fiction writers have a variation on that: “If your plot is flagging, have something horrible happen to your main character. Extra credit if it’s potentially disfiguring.” It’s an effective way to move the story forward, if done right, and how your protagonist reacts to adversity can reveal a lot about their character through action.

Done the wrong way, though, it becomes boring really quickly. Take the last few seasons of the TV show “24.” Keifer Sutherland played a great hardboiled character, but subjecting him to the upteenth gunshot wound, torture session, or literally heart-stopping accident got repetitive. When writing, it always pays to recognize the cliché, and figure out how to subvert it as effectively as possible—the audience will appreciate it.

In A Brutal Bunch of Heartbroken Saps, Bill has done a lifetime of bad stuff. He’s ripped people off, stolen a lot of money, and left more than a few broken hearts. I felt he really needed to really pay for his sins if I wanted his eventual redemption to have any weight. Plus I wanted to see how much comedy I could milk out of a severed finger (readers will see what I mean).

ST: What’s next for you?

NK: I’ve been working on a longer novel (tentatively) titled Boise Longpig Hunting Club. It’s about a bounty hunter in Idaho who finds himself pursued by some very rich people who hunt people for sport. I’ve wanted to do a variation on “The Most Dangerous Game” for years, and the ideas finally came together in the right way. It’s an expansion of my short story, “A Nice Pair of Guns,” which appeared in ThugLit (a great, award-winning magazine; gone too soon.)

ST: What advice do you give to young writers?

NK: A long time ago, the film director Terrence Malick came to my college campus. He was supposed to introduce a screening of his film “The Thin Red Line,” but he never set foot in the theater—unsurprising in retrospect, given his penchant for staying out of sight. However, he did make an appearance at a smaller gathering for students and faculty beforehand.

All of us film and writing geeks, we freaked out. Finally one of us cobbled together enough courage to actually walk up to him and ask for some advice on writing. He said—and you bet I still have this in a notebook—“You just have to write. Don’t look back, just get it all out at once.”

I think that’s the best advice I’ve ever heard. It’s easy to stay away from the writing desk by telling yourself that you’re not quite ready yet, that you’re not in the mood, that somehow the story isn’t quite fully baked in your mind. If you think like that, though, nothing is ever going to have to come out. Even if you have to physically lock yourself in a room, you need to sit down, place your hands on the keyboard, and force it out. The words will fight back, but you’re stronger.

ST: Can you please tell us one random fact about yourself?

NK: I like cats and whiskey.

To learn more about Nick Kolakowski, visit his official website or follow him on Twitter @nkolakowski.

The Writer's Bone Interviews Archive

YA Author Tammar Stein Searches for a Hero in The Six-Day Hero

Tammer Stein

By Lindsey Wojcik

Nearly 50 years ago, Israel and the neighboring Arab states fought in what is now known as the Six-Day War. Just in time for the 50th anniversary in June, young adult author Tammar Stein's The Six-Day Hero will officially be released (it is currently available on Amazon).

While The Six-Day Hero is not directly about the conflict, it does aim to transport readers to the sounds, sights, and events of West Jerusalem during that time. The story follows 12-year-old Motti, a boy who dreams of being a hero, and thinks the only way to become one is by being a soldier like his older brother (who serves in the Israeli army).

Stein, the daughter of Israeli Defense Force soldiers, recently talked to me about her writing process, what inspired The Six-Day Hero, and her advice for other authors.

Lindsey Wojcik: What made you want to pursue writing, specifically young adult fiction?

Tammar Stein: I love books, the physical feel of them, the look of them, the way that they’re gateways to making connections and getting lost in adventures. Even as a young child, I remember my mother scolding me to go outside and get some fresh air because I had been inside reading for hours. It felt inevitable for me to try and create that same kind of magic for someone else.

I never set out to write for young adults, but when my agent read my manuscript for Light Years, she felt it could be a great young adult title. The character was 20 years old; it never crossed my mind that that could be a YA title. But the themes were classic YA: figuring out who you are, who you want to be. We got great response from the YA editors and I never looked back.

LW: What is your writing process like? How has it evolved over time?

TS: My writing process used to be: sit, write, delete, and repeat 50 times. This is not the most efficient way to write a novel. Light Years, my first book, took me five years to write. It turns out that just because I knew a great book when I read it, didn’t mean I could just write a great book myself. My second novel, High Dive, was also kind of a pain to write. I wrote the whole draft of it, almost 300 pages, before realizing it just didn’t have that magic spark. And I started back on page one.

By my third novel, Kindred, I wised up. I outlined. Now I do that for all my books. Not necessarily a detailed breakdown of each chapter, but a strong, two-page outline so I don’t get lost getting from the beginning to the end. It’s harder than it sounds, but it’s helped me so much.

LW: What kind of research went into outlining and writing The Six-Day Hero?

TS: The first thing I did was read. Other than the fact that it lasted six days, I really didn’t know much about the war. So I read dozens of books on the subject. I read newspaper articles from the time period. I watched documentaries. I'm also the daughter of Israeli Defense Force soldiers, and once I had a good sense of the events, I started interviewing Israelis who had experienced the war. Some as soldiers, some as children. I ended up speaking with half a dozen Israelis, including my parents, whom I pestered on a weekly basis for more details.

LW: What made the Six-Day War an intriguing and important topic for you to write a fictional story about?

TS: In 1967, Israel teetered between existence and annihilation. By winning the Six-Day War, it averted annihilation…and began the modern dilemma of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. This summer (June 5-11) marks the war’s 50th anniversary.

The West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and the Jewish Settlements are constantly in the news. If you’ve ever asked yourself, “How in the world did we get into this hot mess?,” the answer is, the Six-Day War. That’s the war that started all this. This is a 50-year-old hot mess. In this book, I look at the history of the war through the eyes of the people living through it. And it's the first English book for younger readers set during the Six-Day War, giving context and perspective to the complexity the world is still trying to solve. I do believe this is a situation that will be resolved one day. We will move on. We will find a way for all these millions of people to live in peace with one another. But to do that, we have to understand how it got started.

You cannot shape the future without knowing the past. But because there are so many hard feelings, because people are tired of constantly hearing about the same conflict, there’s this tendency to just want to move on, to ignore it. Especially when it comes to kids. So there’s no one writing about it, no one publishing about it. And kids are just left in this vacuum. They hear the news, but they don’t have any basis for truly understanding it. I wanted to change that.

To be clear though, the book is not about the war. The book is about Motti, a 12-year-old boy, who wants to feel heroic. But when you read the book, you learn about the history of the war through his eyes. The violent details of war didn’t strike me as the best way to tell a kids’ story. Rather, I wrote a book about the struggles of a 12-year-old, struggles shaped by the same forces that shaped the war. I hope the book will transport young readers to the sounds, sights, and events of West Jerusalem 50 years ago.

LW: What inspired you to write it from a 12 year-old’s point of view?

TS: Motti just came to me. It’s one of the moments that felt almost mystical. I just had this scene pop into my mind: a restless, bored kid forced to sit through an assembly, desperate to get away. Motti is a scrappy boy, always looking for mischief and fun. He struggles to shine in the big shadow cast by his successful older brother, Gideon. Straight-arrow/Gideon is now a soldier in the Israeli army, and Motti is equally proud and jealous. Over the course of the next month, everything Motti knows about Israel, his brother, and himself will be put to the test. He will realize that war is not a game, and he will face harsh challenges to be the hero he always dreamed of.

LW: The Six-Day Hero will be officially released in time for the 50th anniversary of the war. How does the book honor its history?

TS: When you hear that something happened 50 years ago, there’s this reflexive feeling that it’s ancient history. That it barely matters. But I spoke with people who lived it, fought through it, and are still haunted by what happened. The whole world is still being shaped by what happened. It’s far from ancient history, and I wanted to make sure that there was something there for kids to connect to.

LW: What's next for you?

TS: The Six-Day War was just one in a chain of wars for Israel. The history of an Israeli family can really be told by tracing the family’s lives through the wars they fought. Six years later was the Yom Kippur War, and my next book is about Beni, Motti’s younger brother, with the Yom Kippur War as the setting.

LW: What's your advice for aspiring authors?

TS: My best piece of advice is to try to balance a sense of urgency with lots of patience. Both are absolutely necessary to write a book. If you don’t feel urgency, you’ll never write. It’s always much nicer to plan to do it later, in the evening, tomorrow morning, over the weekend. If you don’t feel urgency, you’ll always put it off. But you have to be patient with yourself and your work as well. Your first draft will be terrible. Your sense of urgency will shout at you to share it with your family and friends, to start sending it out to agents, to publish it as an e-book. Don’t do that. You need to go back and revise. Then you let it sit for a month (or three) and come back to it with fresh eyes. And just as you get comfortable with your patience and want to keep tinkering with your manuscript forevermore, your sense of urgency needs to rise up again and urge you to send it out and share it with the world.

To learn more about Tammar Stein, visit her official website, like her Facebook page, or follow her on Twitter @TammarStein.

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

Author Boris Fishman On Immigration and Identity in Fiction

Boris Fishman (Photo credit: Stephanie Kaltmas)

By Adam Vitcavage

Boris Fishman’s latest novel, Don’t Let My Baby Do Rodeo, is about a young Jewish-American couple that immigrates to the United States from Eastern Europe. (You can read my full review in March’s “Books That Should Be On Your Radar.”)

While traveling abroad to participate in panels for the London Jewish Book Fair, Fishman was kind enough to answer some questions via email about his perspective on immigration, global affairs, and his new writing project about food.

Adam Vitcavage: You immigrated to America at a young age. You’ve also been in American longer than I have—I was born a year after you came to the country as a boy. Now, I’d say you’re probably more “American” than I am because, technically, you lived here longer than I. Whatever that means. What has it been like being an immigrant in America in 2017?

Boris Fishman: I’m more curious about your question than my answer. In what way do you feel less American than you imagine I do? My own condition on this is all over the place. Despite having very strong sympathies with their side, I don’t feel like one of the immigrants who are centrally affected by what’s going on in this country right now. But I couldn’t feel less “American” than you imagine me to. (Equally curious why you do.) Perhaps because I was born in another country—and continued to live in it, so to speak, emotionally and psychologically as I grew up in my family home here in the States; the immigration shouldn’t be dated to 9 years old but my post-college twenties, if that—I have very different values when it comes to certain things. More Russian values, more European values. The two areas in which I am proudest to be an American—now under attack—are its rule of law and civil liberties. There are many other issues where that’s less the case. But that doesn’t make me feel like an immigrant. It makes me feel like a foreigner.

AV: In a recent interview you said, “The problem with Russia reporting—just like, say, Iran reporting—is that the political tension makes non-political stories rare.” I’ve noticed a trend since the election that a lot of topics have become politicized in America. Do you feel American rhetoric is shifting in tat direction? Or are we just in a wave of tension right now?

BF: In the Soviet Union, we used to have three television channels. At American airports—I’m writing this at JFK—it feels like there’s only one: CNN. I travel a lot, and there’s no airport gate that isn’t besieged by poor Wolf Blitzer droning on about the same things over and over. (I have to imagine that the airport people are trying to split the difference between Fox and MSNBC.) Meanwhile, serious newspaper journalism—an indispensable safeguard, a civic necessity—is dying. And social media makes it too easy to gaze at no navel other than one’s own, and heap scorn on the other side that one would never dare heap were one doing it to someone’s face. So I’d say not so much that we’re becoming more politicized, but that the loudest among us seem to be eagerly, rapidly becoming stupider and lazier. Less interested in nuance. Less tolerant of dissenting opinion. Less thoughtful before we speak. More gratuitously provocative. More indulgent of our baser instincts. The dominion of social media is one of the reasons it’s so hard for me to feel at home here right now. This country is full of thoughtful, moderate people. But they’re not the ones shouting at us everyday. I’m not on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram. I don’t have a television. But I still can’t escape it.

AV: You recently traveled to Estonia and Latvia to discuss creative life in America. What can you share about the arts and literature in Eastern European countries like those?

BF: There are lots of fascinating things going on there. Estonia, a country the size of your fingertip, is so much more technologically advanced than America is, it’s embarrassing. Riga, in Latvia, is an enchanted place—the best of Europe at a third of the price. Latvia is in a real nationalist mood, which leads them to cut off their noses to spite their faces politically, but on the other hand, it’s so nice to see a capital city untouched by the globalized sameness you see in so many places around the world, from Brooklyn to Moscow and even Tallinn, whose proximity to Finland is curse and blessing both. Latvian food, Latvian fashion designers, Latvian jewelry designers—you get a very strong sense of place. But there’s no way to be in either country without feeling the political shadow cast by Russia next door, and Trump’s abdication of NATO guarantees to the Baltic states. It takes real effort to see past, indeed, the swarming political questions.

AV: This novel explores themes of immigration, acculturation, assimilation, and more. Your first novel touched on similar themes What entices you to explore these topics?

BF: They’ve affected every moment of my life.

AV: When you’re crafting a story to tell, do you write for a particular audience? For Americans? For Jewish immigrants?

BF: I want to write the smartest possible book for the broadest possible audience. What this means is that in my books there are no sinners or saints; no easy feelings; no straightforward answers. Because those things exist in real life very rarely. But that ambiguity, ambivalence, and complexity can never be an excuse for vagueness, diaristic philosophizing, or gratuitous difficulty in the writing. I am fanatical about giving my reader as many tools as I can to help him or her make sense of the human mess I’m describing. So to the extent I imagine an audience, I imagine smart people reading carefully, and I thank them by making it as easy on them as I can. But I’m incapable of doing that by simplifying the story, by making the ideas simpler, the language homelier. And that isn’t for everyone. Someone told me recently, “I was really affected by your book, but I really couldn’t do anything else while I read it.” As far as compliments go, it was a begrudging one. For my part, I don’t want to write a book that would be simplistic enough to make full sense of while watching television or doing the laundry. That book would be a lie, as I see it. But some people read to escape into a better, or easier, world. And that’s okay. We all worship different things.

AV: Writers often embed truths about themselves in their own writing. Did you do that with your last novel? Did you discover anything surprising about yourself?

BF: Yes. I thought I was writing a novel about the many women of my mother’s generation who have given their lives to taking care of the men around them, and then I realized that in writing about an adopted child I was writing about myself. Immigration renders you so foreign to your elders that you might as well be adopted.

AV: Your first novel came out in 2014. This came out in 2016. Can we expect the next book like clockwork for early 2018? If so, can you share a little bit about the project?

BF: I’m in the last third of the first draft, so very possibly! It’s a food memoir. The first part is the story of our Soviet lives, and immigration, told through food—Soviet food was way better than its reputation suggests because it was, by necessity, local, seasonal, and organic, at a cost of next to nothing. Refrigeration technology came late; supply chains were inefficient; agriculture didn’t make industrial use of pesticides in the same way; and so on.

The second part is the story of a woman who came into my family’s life after my grandmother passed away in 2004—a home aide from Ukraine who took care of my grandfather. She was a phenomenal cook, and her tables, not to put too fine a point on it, ended up bringing me back to a family and culture I was trying very hard to abandon. I followed her to Ukraine, and learned to cook from her, and then ran with it on my own: I worked in a restaurant on the Lower East Side for five months.

So Part 3 is all the ways my own time in the kitchen has saved me. I had a very difficult personal experience several years ago; cooking brought me out of it. It was also how I met the woman with whom I now live. And it was our proving ground. We spent the first week of our courtship using some very inadequate tools to cook for 40 screaming Lakota Sioux kids on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota, part of a traveling summer camp for which she was a counselor and I, somehow, a chef.

To learn more about Boris Fishman, visit his official website.

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archives

A Conversation With Girl Through Glass Author Sari Wilson

Sari Wilson

By Adam Vitcavage

Editor’s note: this interview originally appeared on www.vitcavage.com, shortly before Girl Through Glass was originally released in January 2016. You can now purchase the novel in paperback.

Sari Wilson’s debut novel was about a decade in the making. Wilson’s head was filled with images from her childhood as a ballerina: her hair up in a tight bun, blistered feet, and countless leotards. She knew she wanted to write about the world she spent so much time in, but, more importantly, wanted to write about the emotional truth of her time training in ballet and her childhood.

The story grew and grew and became the fanciful novel Girl Through Glass. In the debut, a young rising star in the 1970s ballet world meets a shadowy middle-aged man named Maurice who becomes fascinated with her. In the present, a dance professor deals with her past as a dancer, and must confront what happened to her all of those years ago.

I spoke over the phone with Wilson for what was, according to the author herself, her first interview as an author.

Adam Vitcavage: I know this book came about after you had thought of a short story about ballet. Can you talk about the genesis of how this book came to be?

Sari Wilson: It was a long process. I would say 10 years or more, depending on how you count. I got the image of these girls—which actually became one of the first images in the novel—these young girls putting on their leotards and tights like they’re putting on armor, getting ready for battle. That image came back to me very strongly. It was from my childhood, but I hadn’t thought of it in many years.

It was emotionally powerful to me, but I didn’t know what to do with it. I tried to make it into a short story. It never worked. It just kept getting bigger and bigger. It was so different than anything I had been writing at the time.

I had my own experiences as a young girl in the ballet world that wasn’t so different than a lot of girls’ experiences. I felt that I touched on something that was related to the time period too. New York City, the late 1970s, the early 1980s, all of those Russians. Even though I never studied with the Russians, they were everywhere.

I became very fascinated with all of this, in a writerly way. I went back to the material in that capacity. I interviewed people whom I danced with. I read a ton. That’s when these characters started emerging. They took me over. The girl Mira came first. Her story is not mine, but it’s informed by my experience—people I knew, places I danced. I came to really love her and feel for her. I feared for her, but I had to follow her story until the end. I actually wrote the whole Mira storyline first. The character of Kate came later. I added Kate because I felt it needed an adult frame. She’s a very complex character. I learned—as I wrote—that they were the same person.

AV: So, you didn’t intend for them to be the same person. How and when did you decide that they needed to be the same?

SW: I already had the structure of the book. My job became figuring out who this Kate character was and what her story was. Especially how it related to Mira’s story.

AV: As I was reading the book, it became fascinating to me about how this lovely girl became this fraught middle aged woman.

SW: Yes, it became an exploration into the past. Can we ever escape from our past? How does it transform us?

AV: Speaking of the past. You say that you “stole liberally” from your childhood. How many experiences of yours found their way into Mira’s life?

SW: A lot of the setting was taken from my childhood. For example, the New York City blackout in 1977. I remember that very distinctly. A lot of the description of the ballet studios I danced in. I loved these spaces–they were windows into other worlds. A lot of the girls were based on girls I knew and danced with.

Many of the images and the feelings are drawn from my childhood. Mira’s emotional truth is my emotional truth. Her emotional experiences in the dance world were mine. At the same time, pretty much everything that happens to her is fictional.

AV: How did a character like Maurice come into Mira’s life?

SW: He is completely a fictional character. There was no Maurice in my life.

AV: But are there these types of men who are interested in these young girls? Or was that completely fictional?

SW: Historically, there have been men like this in the ballet world. There are passionate fans known as balletomanes. Ballet lore is filled with balletomanes—and examples of the extremity of their passion for this ballerina or that ballerina. If you look at the [Edgar] Degas ballet paintings, there’s often a shadowy figure. A man, shadowy and hiding behind the curtains.

Maurice is also drawn from some storybook characters. I wanted the book to have some element of a fairytale-feeling in terms of tone. Maurice came out of that. The ballet world is filled with this idea of the mysterious lurking man, and also these passionate, often obsessive balletomanes. To me, Maurice came as part of that world: the story of ballet.

In my life: there were not these men. But, I will say that to be a dancer means to always be watched. There were always people coming into the classrooms and we never knew why. They’d be standing and watching us with clipboards and then whispering and leaving. As I was remembering this world and my childhood experiences, I also remembered girls were chosen for roles in this way. Things happened because you were seen. You didn’t have a voice as a young dancer; only your body. Your body was everything.

AV: It’s just crazy to hear about these types of people. There were moments in the book that were left up to the reader’s imagination. Why was it important to leave out some details?

SW: I would say there were probably 1,000 pages that aren’t in the book—edited out over the years.

AV: That’s fascinating. I wanted more, but I’m not sure I know what I wanted of. I mean this as a compliment. I just needed more of these characters.

SW: I write from images. I write setting and characters, and the plot comes with me later. I have to throw out a lot of what I generate. One of my professors in graduate school was Tobias Wolff. Working with him taught me something about the art of leaving things out. How when you leave something out, you can create more tension and more mystery.

AV: I definitely felt that tension.

SW: I worked a lot in the later stages on the structure. How to create dramatic tension by withholding information. That was always a question I asked myself. Maybe I left out too much in the end. I don’t know. I’m going to need my readers to tell me.

AV: I appreciated the tension. I wanted these characters in my life. I need to read more about ballet because of this book.

SW: That’s awesome. I could not be more thrilled to have someone who basically didn’t know anything about ballet being captured by the mystery of it—as I was as a child. It’s a strange world, it’s a dangerous world, it’s a magical world, and largely it’s a province of girls. I’m thrilled a man would find it compelling.

AV: I read your opinion piece for The New York Times about how it is a dangerous world.

SW: I actually think it’s a good moment for ballet right now. In terms of mainstream culture at least. Misty Copeland is someone everyone is so excited about. She’s a revolutionary dancer who is really shaking things up. Then there’s also a [television show on Starz] called " Flesh and Bone" that covers a lot of the same themes as my novel.

But as much as this book is about ballet, I wanted to write a book about the human condition. Not just a ballet book. I wanted to find what was compelling and tragic and deeply human in all of these characters—and set it in the world of ballet.

AV: You did a good job with these characters. I know nothing about ballet, but I completely understood that attention that Mira wanted. Other than that human connection and the building of tension, what other things do you try to implement stylistically into your writing?

SW: I think my style comes from a lot of years of very hard work. I write a lot, but I haven’t published that much. That’s because I have to be really honest with myself. Am I putting on paper what is absolutely true? Is it the emotional truth? If it’s not then I have to keep going. I do a lot of freewriting, and then I edit most of it out. What remains is the writing that has the most energy and speaks to me the most.

It’s images and character’s voices that come to me first. I do a lot of writing to find who these people are and to figure out where they’re coming from. Then my job becomes the story. Putting everything together is actually the last piece for me. It’s a layered process.

AV: So what’s a normal writing day for you?

SW: Usually, I start where I left off. I leave a note for myself about what questions I have. I usually start out doing free writing to get underneath my conscious mind. When I start to surprise myself is when I think something is moving and interesting. If I’m just trying to generate material, my goal will be a certain number of pages in a day or a session. If I’m in the editing process, I’ll give myself a similar goal of pages to edit.

AV: Are you already onto processing the next project? Hopefully, it’s not another 10-year process for you.

SW: I hope it’s not another 10 years (laughs). I started another one. I started it last spring, and I’m very excited for it. I’m trying to do more advanced planning for this one so it doesn’t take as long. Doing more outlining ahead of time, though I’m sure it will be another layered process.

AV: Can you talk about anything of the book? The characters or emotions you’ve come up with.

SW: I really can’t. It’s too early. I just have some characters and some situations. But it’s too early.

AV: I totally get it. Is that all you’re working on, or do you have any short stories or essays?

SW: I am working on some essays related to the book and ballet. As far as short stories: not at the moment. I’m really compelled by the novel form. I think it has a lot of energy right now.

AV: What about comics at all? I know your husband is a cartoonist.

SW: My husband is a cartoonist, his name is Josh Neufeld, and we are publishing an anthology of linked short stories and comics this spring. It’s called Flashed: Sudden Stories in Comics and Prose. It’s all flash fiction. Some of it is prose and some of it is comics. They’re all in dialogue with each other. There are some great comics and great fiction writers involved. We loved putting them together.

To learn more about Sari Wilson, visit her official website, like her Facebook page, or follow her on Twitter @sariwilson.

Read or listen to more of Adam Vitcavage's interviews by visiting his official website or subscribing to his podcast "Internal Review."

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

Student of Crime Fiction: Author Joe Lansdale Returns to Talk Hap and Leonard

Joe Lansdale

By Sean Tuohy

Author Joe Lansdale’s characters Hap and Leonard have been thrilling readers for years with their mix of sly East Texas humor and violence.

Lansdale swung by to talk about the latest entry in the series, Rusty Puppy, which follows the pair as they investigate a racially motivated murder that could tear their town apart.

Sean Tuohy: In Rusty Puppy we find Hap and Leonard investigating a racially motivated murder? Where did this plot line come from?

Joe Lansdale: Racially motivated murders are nothing new, but there has certainly been a lot of it in the news lately, so it seemed like the right background for a story with concerns about police corruption. I think it was an idea in the back of my mind for a long time, but there just wasn't any plot to stick it to. I don't plot. I get up and write, but my subconscious surely does, and I would guess it was one of the man stories it was working on, and when I sat down to write, that was the door that opened.

ST: Rusty Puppy is a stand-alone that is great for new fans of the series. As the creator, what would you like new readers to take away from this novel?

JL: It's part of the Hap and Leonard series, but like all of the books, it stands alone. You need not have one to read the other. You can start anywhere. Sure, there is information from previous novels, but it's nothing that would cause you to be lost.

ST: This is the latest entry in a much loved and long-running book series. As a writer, how do you keep yourself interested in the characters after all these years?

JL: I don't write about them all the time. I have bursts where I do a couple Hap and Leonard novels, and as of late stories and novellas about them, and then I move on to other things. I love coming back to them. For me, I stop their aging process when I'm not writing about them. I've had eight years between their adventures, and I've had four years. And so on. I write them when I feel driven to do so. I was happy with the television series, so that may have inspired me more. But it's the books that matter.

ST: You’ve been writing Hap and Leonard stores for a while. Do you learn something new about the characters with each passing story? If so, what did you learn about them in Rusty Puppy?

JL: I do learn something new. I think in some ways they are becoming closer than ever, and both of them are developing new relationships in their lives, and they are dealing with growing older. I visualize them both about 50 or so. Again, I stop their aging when I don't write about them.

ST: Rusty Puppy—like the other Hap and Leonard novels—features a great mix of snappy dialogue, violence, and sly humor. Is this unique form of storytelling from East Texas?

JL: It is part of the tradition of crime fiction, snappy dialogue, and it goes with a lot of East Texas culture as well. I'm a student of both.

ST: Where can readers pick up Rusty Puppy and where can they see you to get a signed copy?

JL: I will be doing a lot of signings in late February and early March, those will be posted on my website, my fan page, and Twitter, as well as other places.

To learn more about Joe R. Lansdale, read our first interview with the author. If you need even more Lansdale, listen to Sean’s podcast interview with the talented Kasey Lansdale.

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

Early Morning Paperback Writer: 12 Questions With Author Nicholas Mainieri

Nick Mainieri

By Daniel Ford

I plan on gushing about Nicholas Mainieri’s debut novel The Infinite in greater detail in December’s “Books That Should Be On Your Radar,” but I’ll say this: It's one of the best debut novels I’ve ever read. Everyone should buy the book and read it while scarfing beignets and downing coffee.

Mainieri talked to me recently about his early love of storytelling, how his writing process has evolved, his decision to get an MFA, and what inspired The Infinite.

Daniel Ford: Tell us about your origin story. How did you become a storyteller?

Nicholas Mainieri: I always liked to write stories. I liked that more than speaking them. We had an old typewriter in the house when I was a child, and I found myself retelling stories I’d seen in movies, that sort of thing. Then, when we were given free time to draw or read or whatever in grade school, I’d spend it writing in the back of my notebook. I remember mentally planning stories during recess, knowing I’d have a half hour at the end of the day to write them down. It was just a fun thing, I thought. I imagine a lot of writers had those impulses, growing up. I didn’t discover that storytelling was something one could take “seriously” until I was in college. I’d heard somewhere that to be a writer you just had to get up and do it every day, so that’s what I started doing.

DF: Who were some of your early influences?

NM: For a good few years of adolescence, I read Stephen King almost exclusively. Character, conflict, structure—King’s work was instructive before I realized it. Cormac McCarthy, Leslie Marmon Silko, Ralph Ellison, Antoine de Saint-Exupery, Sandra Cisneros, Junot Díaz, Raymond Carver, Breece D’J Pancake, Stuart Dybek—these were some of the writers I discovered right around the crucial time when I was turning to storytelling as a way of life. Once I had some idea of what I was looking for, my reading tastes tended to especially gravitate toward writers I thought of as interesting stylists.

DF: When you actually sit down to write, what’s your process like? Do you outline, listen to music, devour beignets?

NM: I had some beignets just the other night! Highly recommend Morning Call in City Park when you come to town. Sadly, beignets would likely be an unsustainable part of my process (though I’m willing to give it a shot). I’m an early morning writer. When it is still dark outside, when I am still a little fuzzyheaded from sleep. The voices of doubt are quietest then. When things are going well, I’m up and writing every day. I don’t outline because I like the process of discovery, but I usually keep an open notebook beside the keyboard and fill it with barely legible notes and reminders as I go. When it comes to rewriting, I can do that any time of the day. But for creation, early mornings are best.

DF: There’s an ongoing debate about whether it’s worth it or not to pursue an MFA. You earned yours from the University of New Orleans, so I’m interested to know how you made your decision.

NM: At UNO, I was welcomed into a place that wasn’t pettily competitive or designed to turn me into someone’s cookie-cutter idea of a writer or anything like that; I found a community of hard-working artists that cared about one another and one another’s work. Even while applying to MFA programs, I was pretty uneducated in terms of what they actually are. But UNO turned out to be exactly what I needed, and I imagine that my development as a writer was expedited by such an intensive, artistically focused environment with a built-in audience. I think it would’ve taken me much, much longer to learn certain things about the relationship between the written word and the reader had I not been through an MFA program. And all this before mentioning the many peers and faculty members who became great friends and mentors. As far as the whole MFA debate goes, I don’t know. It’s nice, certainly, if a grad program will provide funding or a tuition break, as that amplifies the worth of the MFA as I see it: an amount of time that one isn’t likely to find otherwise.

DF: What’s the premise of The Infinite and what inspired the tale?

NM: Jonah and Luz, two young people whose histories are informed by loss, meet and fall in love in New Orleans. Luz, who is from Mexico, came to the city with her laborer father in the post-Katrina construction boom; Jonah is born and raised. Both of their lives have been largely shaped by loss, and they find both refuge and hope in each other. When Luz becomes pregnant, however, her father sends her back to Mexico and her grandmother. When Jonah doesn’t hear from her, he sets off on a road trip to visit. Unbeknownst to him, Luz’s homecoming has derailed amid drug war-related violence, and she is fighting to survive.

I had observed a teacher-friend’s classroom in a local high school that had been marked for closure by the city. The school was a pretty chaotic place, the drug trade and attendant violence spilling into the hallways dramatically and often horrifically. In those hallways, though, I met a bunch of funny, smart, and resilient kids who were simply caught amid some tough circumstances. The characters started chattering in my head soon after that.

DF: How long did it take you to write the novel and what was your publishing journey like?

NM: I wrote the first words in the fall of 2010 (the novel is set, mostly, in the spring of 2010). All told, I think the first draft and a bunch of rewrites took me about five years, including finding a home for it. I’m very lucky to have an agent and editor both who understood the novel from the beginning, who saw it as I saw it. It all took as long as it needed to take, the book somehow winding up in the hands of its perfect caretakers. And seeing the final thing in print is a real joy, but it’s also an extraordinary relief—to know that all that time spent writing, and thus separated from my wife and friends and family, amounted to something.

DF: You tackle some pretty big issues for a debut—both post-Katrina New Orleans and the Mexican drug war. How much research did you do before writing the book, and how did you decide on the themes you wanted to explore?

NM: The key experiences that informed the writing can’t be considered research because I had them before the idea for the novel ever occurred to me (a couple summers spent studying in Mexico, moving to New Orleans, visiting the local high school, etc.). But, they created for me a number of memories, impressionistic and backlit with emotional pulse, that lingered and resulted in questions. I wondered about what I’d seen or heard from people. Somewhere in there the novel was born, and so I talked to people and, chiefly, read many things—about the drug wars, about American appetites, about the immigrant experience in New Orleans after the flood.

DF: I love your main characters’ dynamic, which is established right from the get-go. How did you go about developing Jonah and Luz, and how much of yourself ended up in them?

NM: Thanks! In writing young characters I thought an awful lot about how we discover things like love and violence and loss in the world—discoveries we often make when we are young. So, in the abstract, that feels derived from my experience, what I know of these things. In the details, however, neither character has a life that resembles my own. I’m a believer in putting characters on the page and letting them act and interact. I try to bring as much imagination, intelligence, and respect as I can to them, and go from there. The opening pages were written later on in the process (maybe even after a draft had been completed), after I’d discovered the kinds of things that were important to both Jonah and Luz.

DF: The Infinite has generated praise from authors (including Writer’s Bone favorites M.O. Walsh and Philipp Meyer!) and plenty of media outlets. What has that experience been like, and does it give you more confidence as a writer going forward?

NM: It’s exciting! But it is also a scary thing when the first people who are reading your book are authors you love! I was fortunate enough to receive kind blurbs from a handful of them—and that remains one of the more meaningful parts of the whole process. I’m still searching for adequate ways to say thank you. Confidence…maybe I feel more confident, I don’t know. Blurbs or reviews or whatever, they at least give me a bit more to combat those negative voices that arise inside my own head while writing.

DF: Speaking of going forward, what’s next for you?

NM: Well, two things. I’m working on a new novel and happy to be doing so. Transitioning out of the headspace required by The Infinite was difficult in some respects, but finding a new story to tell is exciting. I’d say more about the project but it is still early yet and I’m superstitious about that sort of thing!

Secondly, my wife and I have been working on another fun project that is based on her experience tending bar in a few iconic barrooms and my experience drinking in them. We’re hoping to be able to do something with that book soon.

DF: What’s your advice to aspiring authors?

NM: Get up every day and do the thing. Don’t rush. Every word you write is necessary, regardless of which ones end up in print.

DF: Can you please name one random fact about yourself?

NM: Crystal Hot Sauce is my favorite hot sauce.

To learn more about Nick Mainieri, visit his official website, like his Facebook page, or follow him on Twitter @NickMainieri.

The Writer’s Bone Interview Archives

A Conversation With Christodora Author Tim Murphy

Tim Murphy (Photo credit: Chris Gabello)

By Daniel Ford

As I wrote in November’s “Books That Should Be On Your Radar,” I was completely enthralled by Tim Murphy’s novel Christodora.

Murphy graciously answered some of my questions recently about his addiction to reading and writing, nonlinear storytelling, and what inspired Christodora.

Daniel Ford: Did you find writing or did writing find you?