Dissecting A Decade-Long Writing Process With The Incendiaries Author R.O. Kwon

Giving Back to the Universe: 8 Questions With Fantasy Author Mackenzie Flohr

Exploring the Human Animal With Crime Fiction Novelist Nick Kolakowski

Nick Kolakowski

By Sean Tuohy

Author Nick Kolakowski loves crime fiction. From his work with ThugLit, Crime Syndicate Magazine, and his upcoming novel A Brutal Bunch of Heartbroken Saps (out May 12), it’s easy to tell that the author truly values the hardboiled crime-fiction genre and knows how to write it well.

Kolakowski sat down with me recently to talk about his love for the genre, the seed that created the storyline for his new novel, and “gonzo noir.”

Sean Tuohy: What authors did you worship growing up?

Nick Kolakowski: I always had an affinity for old-school noir authors, particularly Raymond Chandler and Jim Thompson. What I think a lot of crime-fiction aficionados tend to forget is that a lot of the pulp of bygone eras really wasn’t very good: it was all blowsy dames and big guns and writing so rough it made Mickey Spillane look like Shakespeare. But writers like Chandler and Thompson emerged from that overheated milieu like diamonds; even at their worst, they offered some hard truth and clean writing.

ST: What attracts you to crime fiction, both as a reader and a writer?

NK: I feel that crime fiction is a real exploration of the human animal. You want to explore relationships, pick up whatever literary tome is topping the best-seller lists at the moment. You want a peek at the beast that lives in us, crack open a crime novel. As a reader, it’s exciting to get in touch with that beast through the relatively safe confines of paper and ink. As a writer, it’s good to let that beast run for a bit; I always sleep better after I’ve churned out a lot of good pages.

ST: What is the status of indie crime fiction now?

NK: I’d like to think that indie crime fiction is having a bit of a moment. A lot of indie presses are doing great work, and highlighting authors who might not have gotten a platform otherwise. Crime fiction remains one of the more popular genres overall, and I’m hopeful that what these indie authors are producing will help fuel its direction for the next several years.

Not a whole lot of authors are getting rich off any of this, but writing isn’t exactly a lucrative profession. There’s a reason why all the novelists I know, even the best-selling ones, keep their day jobs. We’re all in it for the love.

ST: What is your writing process? Do you outline or vomit a first draft?

NK: I keep notebooks. Over the years, those notebooks accumulate fragments: sometimes a line of two I’ve overheard on the subway, but sometimes several pages of story. Usually my novels and short stories start with a kernel of an idea, and I start writing as fast as I can; and as I start building up a serious word count, I begin throwing in those notebook fragments that seem to work best with the scene at the moment. It’s a haphazard way of producing a first draft, and it usually means I’m stuck in rewrite hell for a little while afterward as I try to smooth everything out, but it does result in finished manuscripts.

I simply can’t do outlines. I’ve tried. But outlining has always felt very paint-by-numbers to me; once I have the outline in hand, I’m less enthused about actually writing. But I know a lot of other writers who can’t work without everything outlined in detail beforehand.

ST: Where did the idea for A Brutal Bunch of Heartbroken Saps come from?

NK: A long time ago, I was in rural Oklahoma for a magazine story I was writing. It was early February, and the land was gray and stark. Near the Arkansas border, I saw a Biblical pillar of black smoke rising in the distance; as I drove closer, I saw a huge fire burning through a distant forest. This would be a really crappy place for my car to die, I thought. It would suck to be trapped here.

So that real-life scene rattled around in my head for years. Eventually I began depositing other figures in that landscape—Bill, the elegant hustler, based off a couple of actual people I know; an Elvis-loving assassin; crooked cops—to see how they interacted with each other. The result was funny and bleak enough, I thought, to commit to full-time writing.

ST: You referred to A Brutal Bunch of Heartbroken Saps as “gonzo noir.” Can you dive into that term?

NK: I love crime fiction, but a lot of it is too serious. That seems like an odd thing to say about a genre concerned with heavy topics like murder and misery, but more than a few novels tend to veer into excessive navel-gazing about the human condition. As if injecting an excessive amount of ponderousness will make the authors feel better about devoting so many pages to chases and gunfire.

But real-life mayhem and misery, as awful as it can be, also comes with a certain degree of hilarity. You can’t believe this dude with a knife in his eye is still prattling on about football! A reality television star might dictate whether we end up in a thermonuclear war! And so on. With gonzo noir, I’m trying to blend as much black humor as appropriate into the plot; otherwise it all becomes too leaden.

ST: Your main character, street-smart hustler Bill, is on the run from an assassin and finds himself in the deadly hands of some crazed town folks. Why do writers, especially in the crime fiction genre, like to torture their characters so much?

NK: Raymond Chandler once said something like: “If your plot is flagging, have a man come in with a gun.” I think a lot of current crime-fiction writers have a variation on that: “If your plot is flagging, have something horrible happen to your main character. Extra credit if it’s potentially disfiguring.” It’s an effective way to move the story forward, if done right, and how your protagonist reacts to adversity can reveal a lot about their character through action.

Done the wrong way, though, it becomes boring really quickly. Take the last few seasons of the TV show “24.” Keifer Sutherland played a great hardboiled character, but subjecting him to the upteenth gunshot wound, torture session, or literally heart-stopping accident got repetitive. When writing, it always pays to recognize the cliché, and figure out how to subvert it as effectively as possible—the audience will appreciate it.

In A Brutal Bunch of Heartbroken Saps, Bill has done a lifetime of bad stuff. He’s ripped people off, stolen a lot of money, and left more than a few broken hearts. I felt he really needed to really pay for his sins if I wanted his eventual redemption to have any weight. Plus I wanted to see how much comedy I could milk out of a severed finger (readers will see what I mean).

ST: What’s next for you?

NK: I’ve been working on a longer novel (tentatively) titled Boise Longpig Hunting Club. It’s about a bounty hunter in Idaho who finds himself pursued by some very rich people who hunt people for sport. I’ve wanted to do a variation on “The Most Dangerous Game” for years, and the ideas finally came together in the right way. It’s an expansion of my short story, “A Nice Pair of Guns,” which appeared in ThugLit (a great, award-winning magazine; gone too soon.)

ST: What advice do you give to young writers?

NK: A long time ago, the film director Terrence Malick came to my college campus. He was supposed to introduce a screening of his film “The Thin Red Line,” but he never set foot in the theater—unsurprising in retrospect, given his penchant for staying out of sight. However, he did make an appearance at a smaller gathering for students and faculty beforehand.

All of us film and writing geeks, we freaked out. Finally one of us cobbled together enough courage to actually walk up to him and ask for some advice on writing. He said—and you bet I still have this in a notebook—“You just have to write. Don’t look back, just get it all out at once.”

I think that’s the best advice I’ve ever heard. It’s easy to stay away from the writing desk by telling yourself that you’re not quite ready yet, that you’re not in the mood, that somehow the story isn’t quite fully baked in your mind. If you think like that, though, nothing is ever going to have to come out. Even if you have to physically lock yourself in a room, you need to sit down, place your hands on the keyboard, and force it out. The words will fight back, but you’re stronger.

ST: Can you please tell us one random fact about yourself?

NK: I like cats and whiskey.

To learn more about Nick Kolakowski, visit his official website or follow him on Twitter @nkolakowski.

The Writer's Bone Interviews Archive

Student of Crime Fiction: Author Joe Lansdale Returns to Talk Hap and Leonard

Joe Lansdale

By Sean Tuohy

Author Joe Lansdale’s characters Hap and Leonard have been thrilling readers for years with their mix of sly East Texas humor and violence.

Lansdale swung by to talk about the latest entry in the series, Rusty Puppy, which follows the pair as they investigate a racially motivated murder that could tear their town apart.

Sean Tuohy: In Rusty Puppy we find Hap and Leonard investigating a racially motivated murder? Where did this plot line come from?

Joe Lansdale: Racially motivated murders are nothing new, but there has certainly been a lot of it in the news lately, so it seemed like the right background for a story with concerns about police corruption. I think it was an idea in the back of my mind for a long time, but there just wasn't any plot to stick it to. I don't plot. I get up and write, but my subconscious surely does, and I would guess it was one of the man stories it was working on, and when I sat down to write, that was the door that opened.

ST: Rusty Puppy is a stand-alone that is great for new fans of the series. As the creator, what would you like new readers to take away from this novel?

JL: It's part of the Hap and Leonard series, but like all of the books, it stands alone. You need not have one to read the other. You can start anywhere. Sure, there is information from previous novels, but it's nothing that would cause you to be lost.

ST: This is the latest entry in a much loved and long-running book series. As a writer, how do you keep yourself interested in the characters after all these years?

JL: I don't write about them all the time. I have bursts where I do a couple Hap and Leonard novels, and as of late stories and novellas about them, and then I move on to other things. I love coming back to them. For me, I stop their aging process when I'm not writing about them. I've had eight years between their adventures, and I've had four years. And so on. I write them when I feel driven to do so. I was happy with the television series, so that may have inspired me more. But it's the books that matter.

ST: You’ve been writing Hap and Leonard stores for a while. Do you learn something new about the characters with each passing story? If so, what did you learn about them in Rusty Puppy?

JL: I do learn something new. I think in some ways they are becoming closer than ever, and both of them are developing new relationships in their lives, and they are dealing with growing older. I visualize them both about 50 or so. Again, I stop their aging when I don't write about them.

ST: Rusty Puppy—like the other Hap and Leonard novels—features a great mix of snappy dialogue, violence, and sly humor. Is this unique form of storytelling from East Texas?

JL: It is part of the tradition of crime fiction, snappy dialogue, and it goes with a lot of East Texas culture as well. I'm a student of both.

ST: Where can readers pick up Rusty Puppy and where can they see you to get a signed copy?

JL: I will be doing a lot of signings in late February and early March, those will be posted on my website, my fan page, and Twitter, as well as other places.

To learn more about Joe R. Lansdale, read our first interview with the author. If you need even more Lansdale, listen to Sean’s podcast interview with the talented Kasey Lansdale.

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

‘Writing Is Re-Writing:’ 11 Questions With Author Anne-Marie Casey

Anne-Marie Casey (Photo credit: Brigid Harney)

By Daniel Ford

Liddy James, the “modern-day superwoman” featured in author Anne-Marie Casey’s recently published novel The Real Liddy James, has more job titles than most caped crusaders: top New York City divorce attorney, best-selling author, and mother.

Casey, who is also a screenwriter and playwright, dramatically explores what happens when James’s world beings to unravel. Author Elin Hilderbrand calls The Real Liddy James a “whip-smart and crackling with energy,” and author Marian Keyes says the tale is, “witty, clever, elegantly-written, fascinating, and wise.”

Casey talked to me recently about being a vociferous reader, what inspired The Real Life Liddy James, and, of course, beef stew!

Daniel Ford: My fiancée and I recently traveled to Ireland and fell in love with the country. Before anything else, I need to know where to go to find the best beef stew the next time I’m there!

Anne-Marie Casey: I think it’s hard to find a good beef stew in a restaurant anywhere (I recommend my own really) but people tell me the best is to be found in The Quays Irish Restaurant in Temple Bar, Dublin.

DF: Did you find writing or did writing find you?

AMC: I was always a vociferous reader and studied English at University, so I suspect a career involving literature was somehow inevitable. But in my twenties I was very focused on being a television and film producer and running my own production company, so becoming a writer evolved when my life priorities changed and, bluntly, I got married and had kids. So the answer to your question is that it was a combination of both.

DF: Who were some of your early influences?

AMC: From a young age I adored the Brontës, then at University I became obsessed with George Eliot and Virginia Woolf. In terms of contemporary writers who have influenced me as a novelist, of course, Norah Ephron, Melissa Bank, Rachel Cusk, and, my current top favorite, Elizabeth Strout.

DF: Since you’re also a screenwriter and playwright, I’m curious to know if your writing style differs widely when you’re writing fiction.

AMC: Because I started my career as a script editor, then producer, then screenwriter I am a natural plotter and find structuring a story comes relatively easily to me. I also tend to rely heavily on dialogue. When I decided to write fiction, my challenge was to loosen up a bit and allow space for character description and interior monologue.

DF: What is the premise of The Real Liddy James and what inspired the tale?

AMC: Liddy James is one of New York City’s top divorce lawyers, a successful author and a single mother of two, who seems to juggle her complicated life with ease. But it turns out that she doesn’t! The inspiration for the book was the Anne-Marie Slaughter article from 2012, “Why Women Can’t Have It All,” and that became its main theme.

DF: How much of yourself—and the people you have daily interactions with—did you put into your main characters? How do you develop your characters in general?

AMC: Inevitably, I draw on my own experiences and those of my friends when I am writing. It happens that my first two novels have been contemporary and feature characters more or less around my age (at least when I started writing them!) But I know from writing plays and screenplays that emotional experience is valid whatever the setting. When I am developing a character I always consider the person’s flaws, as I think that is the best way to make them interesting.

DF: When you finished your first draft, did you know you had something good, or did you have to go through multiple rounds of edits to realize you had something you felt comfortable taking to readers?

AMC: I knew there was a compelling character in the first draft, but it took a few drafts to ensure that I was telling a story rather than dramatizing the issue of work/life balance for women.

DF: The Real Liddy James has garnered praise from critics, your fellow authors, and readers. Do those reactions give you more confidence as a writer?

AMC: Yes. Every time one person likes your work you know some other people will too. I want readers and I want them to enjoy what I’m doing. However, I think it’s important that all writers step back and view their careers over the long haul. In a lifetime of writing there will be some projects that are better received than others, some even may be disastrous, the point is to keep going.

DF: What’s next for you?

AMC: I am currently writing a screenplay based on a novel The Master by Jolien Janzing about Charlotte Brontë’s time in Brussels and her secret love for her professor, which inspired Villette and Jane Eyre.

DF: What’s your advice for aspiring authors and screenwriters?

AMC: If you are determined to write something keep going, however dreadful you think your first draft is, as writing is re-writing. And always stop writing when you are in the flow so you have something to pick up on the next day.

DF: Can you please name one random fact about yourself?

AMC: I love cooking and if I weren’t a writer I’d work in a restaurant kitchen.

To learn more about Anne-Marie Casey, visit his official website or like her Facebook page.

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

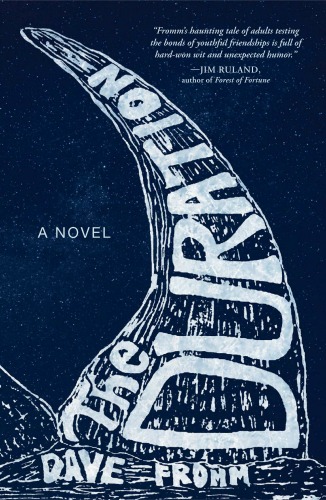

Ghosts of the Past: 11 Questions With The Duration Author Dave Fromm

David Fromm

By Daniel Ford

There’s a paragraph early in author Dave Fromm’s novel The Duration, that made me think he was Writer’s Bone’s kind of author:

The coffeehouse, an anti-Starbucks catering to the same South End crowd willing to spend $5 on a latte, was the sort of place I liked to mock while still frequenting. Their pumpkin muffins were obscene—each one a boulder of orange dough, big as your head, that left oil stains soaking through the to-go bag; sometimes they dropped a few green pumpkinseeds on the top to pretend it was a salad—and I’d sworn on several occasions, usually just after finishing one, to never eat another. Course, I was about to bust into one right then.

Mmm…pumpkin muffin…

The author also endured himself to us saying we had a “very cool website.” Fromm talked to me recently, in an attempt to “lower the cool quotient a little bit,” about finding his voice, his publishing journey, and what inspired The Duration.

Daniel Ford: Did you grow up wanting to become a writer or did the desire to write grow organically over time?

Dave Fromm: Both, I guess, though maybe not in the way you meant.

On the one hand, I was a reader when I was young and grew up wanting to be better at some of the things that “writers” seemed to do—to be imaginative, to create worlds, to express myself clearly, to be empathetic and clear-eyed and rational. I also had a childhood stutter, which, while mild, I was self-conscious about. It pushed me toward writerly observation, rather than engagement, in a lot of social situations. I don’t know if that actually made me want to write, but it seems like a nice vulnerable detail to mention.

On the other hand, I also wanted to be perceived as a writer by my adolescent peers, and especially by my female peers, because I thought it had some cachet value. Writers were obviously brooding and romantic. They had depth. I lacked a lot of things in adolescence, and depth was a big one.

Eventually, these dual tracks—the desire to develop some of the attributes that go into good writing and the desire to be perceived as a writer—came together and I figured I should start trying to write some things.

DF: Who were some of your early influences?

Fromm: Loudon Swain, Lloyd Dobler, Robin Hood, D’Artagnon, Michael Jordan, my parents. Not in that order.

Re: writing, my middle-school English teacher Elfrieda Pierce, my high school Humanities teacher Jim Hurley. I read a ton of fantasy as a kid: The Lord of the Rings, the Shannara knock-offs, Wrinkle in Time, Piers Anthony, Anne McCaffrey, etc. In high school, I liked Ragtime a lot, or at least I remember thinking I liking it. I won an award that came with a biography of William Faulkner but I still haven’t read it. A college friend gave me Fever Pitch, by Nick Hornby, and around the same time I was reading David Foster Wallace’s essays from A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again and Michael Chabon’s debut novel The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, and I guess those three, each in different ways, sort of opened up the world of contemporary literature for me, writing that could be funny and honest and smart and gorgeous and take these complicated ideas and present them clearly. Written by people who were still alive, and were indeed not far from my own age. Also Padgett Powell’s Edisto stories.

DF: What is your writing process like? Do you listen to music? Outline?

Fromm: My writing process is disgraceful. I’m not very disciplined. I have two kids in elementary school, and since they’re there right now I will take the opportunity to blame them.

I do listen to music. For what it’s worth I listened to a lot of Bob Schneider and The Avett Brothers while writing The Duration. I don’t outline very well. It almost works in reverse—I’ll write a chunk and then try to diagram what I already have, and it’s usually a totally screwy diagram, it’ll look like a M.C. Escher diagram, with stairs going nowhere and a flock of birds, and then I’ll try to use that to make sense of what I’m trying to say.

When I can get sort of inspired by something, sometimes momentum will take over and I’ll have a really good run of weeks or months of writing at set times, or in pockets of time late at night or what have you, and I’ll be able to generate a bunch of stuff. That’s what happened when I wrote The Duration. I started it and stuck with it through the first 10,000 or 15,000 words, and then it started to roll and it was all I could think about. I’d even have dreams about it. When it was “finished,” I wrote a collection of nonfiction and a YA novel and then a movie treatment and I was like I am the baddest badass on the planet. I am a machine! And then I got off track and I haven’t really written anything good since early 2015, other than a couple of dope tweets and status updates. Part of it was the publishing process, doing edits to The Duration, building social media stuff, time spent working on something from the past to make it better rather than generating new stuff, even if that new stuff would invariably be crummy. And part of it was laziness.

But recently I got a story idea, and I am going to nurture that idea like a baby bird.

DF: How did you develop your voice? Are you able to slip into it during the writing process or is it something you find while you’re editing?

Fromm: I developed my voice by listening to myself talk and then asking myself, “What would this guy sound like if he was smarter and/or funnier?” I’m only half-kidding. In The Duration, the narrator sounds like a version of me, but a younger, wilder and more heartfelt version. He’s sort of angry and sort of fearful and covers it up with blustery adolescent humor. In this case that voice came pretty easily while writing and part of the struggle in the editing process was not to lose that voice while patching various holes in plot and motivation and stuff. I don’t know what will happen in the next novel, if there is a next novel. There’s an older novel, still in a file, with a main character who also has a voice like mine. It’s starting to feel creepy.

DF: What inspired The Duration?

Fromm: The Duration was partially inspired by a true story from my Western Massachusetts hometown about a touring circus elephant that died in the woods in 1851. The elephant, whose name was Columbus, was so big that the circus folks left him where he fell, and the woods quickly swallowed up the body. He’s never been found, although some folks are pretty sure they know where he is. The idea of this exotic secret buried in a small New England village, and of local kids looking for it, is sort of the first-level plot device in the novel.

The second-level plot device (what does that even mean? I don’t know) is about how certain formative childhood relationships—with close friends, with events, and even with an environment—stay with us our whole lives. How we never really lose them. I started writing The Duration shortly after my wife and I moved back to Western Massachusetts after seven years in California and I started reconnecting—painfully, joyfully, unsettlingly—with the touchstones of my youth.

DF: How much of yourself—and the people you have daily interactions with—ends up in your main characters? How do you develop your characters in general?

Fromm: I don’t know. A lot, probably. I mean, you work with what you have, what you can feel, right? You steal little pieces here and there. A guy has a great nickname, a woman has a funny habit that suggests something about her inner life. I’m lucky enough to be surrounded by people who are smarter and funnier and more interesting than I am, so I borrow a lot. It’s tricky, though, because whenever you use a real-life detail in fiction, the person whose real-life detail it is is implicated, even if the character goes in an entirely different direction.

But, I mean, isn’t every character a version of the author? Even the bit players?

As far as development goes, I guess I try to figure out who I need, what function each character plays, and then try and imagine them as real people. I read something that the writer Steve Almond said once about loving your characters, and I guess that’s not, like, mind-blowingly original advice, but it’s always helped me when I’m working out a scene, to try to empathize with each character and their inner motivations for doing something, so that they become more than just devices. On that front, a helpful exercise has been writing nonfiction pieces and then sending them to the people mentioned in them for editorial feedback. I had a few essays about high school girlfriends and the process of sending the essays to them for review was really helpful in terms of seeing multiple perspectives. Also, terrifying.

DF: How long did it take you to write The Duration and what was your publishing journey like?

Fromm: I feel like I’m still writing it, or I would if I could. I’m glad it’s out of my hands.

The initial drafting process was relatively quick, maybe six months? After that, I sought feedback from a few writing friends, which necessarily takes a while because you can’t just drop a first draft in someone’s lap and be like get back to me in a week? They have their own lives and their own work and all that. But they gave me some really helpful feedback, then my agent did, and then we submitted to publishers. That process also takes a while, and the whole time you’re thinking “no news is good news, right?” But not always. Maybe a year went by? I didn’t have much success with the larger publishers and after a while I just started asking my more successful writer friends what their publishing experiences had been like. One of them, Jim Ruland, had recently published a wonderful debut novel called Forest of Fortune with a smaller publisher called Tyrus Books. He recommended them highly, but they were closed for submissions. So Jim actually emailed the publisher to see if they’d be interested in taking a look at my story. Obviously I’m naming all my future children after him.

Once I hooked up with Tyrus, the publishing journey was smooth sailing. They’ve been great—organized, encouraging, responsive, personal, and really sharp. I feel like I’ve lucked out at every turn.

DF: Most of the authors we talk to prefer to leave the discussion of themes to their readers, but were there any specific themes you wanted to explore while writing the novel?

Fromm: Well shit, now I feel like I should leave the discussion of themes to my readers too. But there’s probably only going to be, like, 10 of them, and I feel like I’ve already asked too much of them anyway.

I wanted to explore the sort of continuity that develops for people at a time and a place. In my case, the continuity is with the area I grew up in and the people I grew up with. It’s more than friendship, it’s a sort of kinship and sense of belonging, for better or worse. My characters, like the town they return to, carry and are nourished by the ghosts of the past and have to figure out how that translates into their ability to go forward, to go on.

DF: Now that you have your first novel under your belt, what’s next for you?

Fromm: I’m shopping something right now that’s a real departure from The Duration, so it doesn’t exactly feel like a “next” thing, but fingers crossed. It’s YA-ish, I guess. A story about an orphan girl who discovers that her grandfather was the last in a long line of pirates and sets out to return his ill-gotten loot. I wrote it for my daughter, who’s only five now but will someday be forced to read it. I’m also starting to work on this new idea, which, at least today, has something to do with a middle-aged guy who starts to fear the approach of some metaphysical enemy, so he takes up CrossFit. It’s fiction.

But first I’m driving out to Monson to pick up some beer.

DF: What’s your advice to aspiring authors?

Fromm: Oh, man. So leery of offering advice because, like, what do I know? Focus on being a writer and don’t worry about being an author? That’ll come, or it won’t. You probably won’t make much money, so if you need that maybe go a different way professionally? But don’t give up? Is that too cliché? Keep working, keep being a decent and generous human being. Engage with the world? Do dumb shit. Read whatever you like to read? Question your motivations? Believe in karma? Make good friends?

DF: Can you please tell us one random fact about yourself?

Fromm: I hate eggs.

To learn more about David Fromm, visit his official website or follow him on Twitter @dfro.

The Writer's Bone Interviews Archive

Author Charles Ardai On Adapting Shane Black’s ‘The Nice Guys’

A Woman of Words: 10 Questions With Author Lynn Rosen

Lynn Rosen

By Daniel Ford

Lynn Rosen’s debut novel A Man of Genius has all the hallmarks of a hit: an unreliable, playboy narrator, well-written suspense, and, of course, a murderous plot.

Rosen revealed to me that she considers herself more of a storyteller than a writer, and from what I’ve read so far of A Man of Genius, she’s far too modest in her self-assessment. There’s an old school charm and elegance to her prose—perhaps owing to her “long years of a rich life”—that speaks to a confidence authors more than half her age have trouble conjuring.

The octogenarian author talked to me recently about her writing rituals, tips for becoming a storyteller, and what inspired A Man of Genius.

Daniel Ford: Did you grow up wanting to become a writer or did the desire to write grow organically over time?

Lynn Rosen: I didn’t grow up wanting to become anything—except to simply grow up. In my youth, which was many years ago, little was expected of females outside of marriage and motherhood. My desire to write grew from loneliness and finding that those who populated the stories in my mind were great listeners and, best of all, served me better than the dolls I played with, for the characters in my mind were much fuller and more malleable.

DF: Who were some of your early influences?

LR: My earliest influence was Inez Haynes Gillmore Irwin, a feminist and political activist who, in the early to mid-20th century, wrote a series titled “Maida’s Little Shop.” Maida has been paralyzed, but with great effort has recovered the use of her legs. Acknowledging her efforts, her loving wealthy father gives her all her heart desires, including a little toy and trinket shop. At the time I met Maida, I was unable to walk as a result of paralytic polio. Maida drew me to a very early realization of the power of literature: the worlds it draws you into, its ability to disclose life’s possibilities, and the mirror it holds up to your own life.

After Irwin, Daphne duMaurier, Charlotte Bronte, Jane Austen, and Laurence Sterne grabbed my attention. DuMaurier and Bronte for their application of the Gothic with its use of the sublime, Austen for her enviable ability to frame a social scene, and Sterne for his awesome control of plot and time lines.

DF: What’s your writing process like? Do you outline, listen to music, etc.?

LR: I do listen to music as I write—in fact one particular piece of music, a disc titled “The Memorable & Mellow Bobby Hackett.” I play, replay, and replay it, over and over again. I’m a very slow writer.

DF: How did you develop your voice? Are you able to slip into it during the writing process or is it something you find while you’re editing?

LR: My voice was established early in the process of writing A Man of Genius. It emerged from my need to develop the work from the outside in—from its binding theme to plot, and character development, which, I hoped, would sustain the theme and contribute to a sense of an organic whole.

DF: What’s the premise of A Man of Genius and what inspired the novel?

LR: The premise of the novel is a series of overarching questions that focus on our relationships with our personal human idols. Who do we elect to revere? What is our criteria for selection? How much of our idols’ foibles are we willing to forgive? All of this inquiry was initiated and sustained by a very old memory of an unexpected meeting I had with Olgivanna Wright at Taliesin, when I was a young undergraduate. For many years I wondered why that particular memory stayed with me. In time, I began to realize the binding force that sustained it was the question of personal idolatry, and what that idolatry says about the idolater. Years passed, during which the memory took on new forms and new perceptions—as memories do. Finally, it emerged in its new form as A Man of Genius.

DF: How much of yourself ended up in your characters? How do you develop your characters in general?

LR: Little of myself ends up in my characters. I develop and move my characters always in support of the over-arching theme that drives the novel.

DF: The unreliable narrator has become a literary trend the last couple of years. What made you decide on that convention, and how did you make your story unique?

LR: I believe all narrators are unreliable; few openly admit their biases, though they usually emerge in time. I believe that the unresolved ending of A Man of Genius demands an unreliable narrator aware of his limitations. If the narrator were presented as reliable, the alternate possibilities that run through the story line would not be sustainable.

DF: What were some of the themes you wanted to explore in the novel?

LR: Idolatry and forgiveness are the major themes. What I wanted most was to bring the readers to a point where exploring the book’s themes resulted in an exploration of the reader’s own systems of moral obligation.

DF: How’s it feel to publish your first novel at age 84, and what was your publishing journey like?

LR: I never thought of myself as a writer—in fact, to this day I haven’t reached that stage of self-identification. I think of myself as storyteller. I love a good story and enjoy sharing one with others. I began writing in my pre-teens during World War II. With my father away in the service, I had a great deal to say and nobody would listen, so I wrote letters to the editor of The New York Times and some were printed, and people began to listen and write back through the paper. Then there were articles about books I read, and some of those also were printed—a short story was published and I wrote several drafts of novels that now sit snugly in files in my office. Perhaps they’ll now see the light of day because I’m beginning to think I just might be a writer. I believe that, whatever one accomplishes in life has little to do with age, and everything to do with attitude. If anything, long years of a rich life, as mine was and is, expands a writer’s possibilities. In the end it all resides in the mind and spirit.

DF: What’s your advice to aspiring authors?

LR: Don’t decide to become a writer and then go poking about looking for a story. Discover a story that you find compelling and become a writer.

DF: Can you please tell us one random fact about yourself?

LR: In my mind I’m 33 years of age. I’ve been frozen there for a very long time. Don’t ask me why. Personally it wasn’t a particularly outstanding year.

To learn more about Lynn Rosen, visit her official website, like her Facebook page, or follow her on Twitter @authorlynnrosen.

The Writer's Bone Interviews Archive

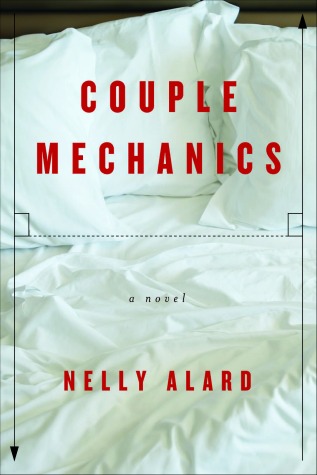

Love & Other Themes: A Conversation With Couple Mechanics Author Nelly Alard

Nelly Alard (Photo courtesy of Stephane de Bourgies)

By Stephanie Schaefer

If you’re seeking entertainment in the form of a passionate love triangle, skip next season of “The Bachelorette” in favor of author Nelly Alard’s Couple Mechanics.

Library Journal called Alard’s U.S. debut “an intimate, claustrophobic, and compulsive read,” and Kirkus Reviews said it packed “a surprising, emotional wallop.”

Last month, Daniel Ford and I attended a talk with Alard at the charming Porter Square Books in Cambridge, Ma., where she spoke about differing views on love and marriage, Simone de Beauvoir’s influence, and how she crafted her novel’s provocative opening scene.

Find out more about how she develops characters and what inspired Couple Mechanics by reading my interview with the author below.

Stephanie Schaefer: When did you decide you wanted to become a writer?

Nelly Alard: I actually never decided that, it sort of happened. I wanted to be an actress. I started by helping a friend director to write a screenplay based on a story he had in mind. It seems I was not bad at it and the movie got produced and then other people hired me to write for them and I did it, mostly for the money. I was having a hard time making ends meet as an actress and people offered me good money to write screenplays. My first novel Le Crieur de Nuit, was my first attempt to write something “personal” and it was picked up right away by Gallimard, which is the most prestigious publisher in France. And then I realized that not only was I more successful at it, but I actually enjoyed writing much more than acting, at the end of the day. And that’s how I became a writer. I have been incredibly lucky!

SS: Who were some of your early influences?

NA: As a child I would know by heart entire scenes of Racine and Corneille, and I loved reading the great classics pretty early on. So I would say Balzac and Tolstoï. Later, I developed a passion for Proust. I discovered American writers much later.

SS: What’s your writing process like? Does your fiction writing process differ from your screenwriting process?

NA: The main difference is that a novel is really the creation of one single person—the author—from the very beginning (the original idea) to the end, and that singularity is what you’re looking for. To find your unique “voice” is probably what matters most in writing a novel. A screenplay is only a basis for a collective work. Even if you write it entirely alone (which never happened to me), it never stands by itself and will be altered by the director, the producer, or the actors on the set. Also, when you write a screenplay you have to keep in mind the cost of every single scene you write! The word that comes to my mind when I think of novel writing as opposed to screenwriting is freedom!

SS: What inspired Couple Mechanics?

NA: It’s a mixture of different love affairs I’ve either experienced, or seen around me. I wanted to revisit The Woman Destroyed by Simone de Beauvoir, which was written in 1968 and tells pretty much the same story than Couple Mechanics does, and see how this story would unfold some 50 years later, after the feminist revolution has changed the relationships between men and women so much.

SS: How much of yourself ended up in your characters? How do you develop your characters in general?

NA: Oh, there’s a bit of me in every character. In Juliette, of course, but also in Victoire, and even in Olivier. The chapters written from his point of view were actually the ones I enjoyed writing the most (those chapters were cut out of the English version). It’s fun to become a man for a few pages! All my characters are monsters, and a combination of two or three people I know. They have the feet of somebody, the face of somebody else. And then you grab things here and there, people you know, things you heard. And the character begins to have a life of its own. Most of the time you don’t even know where it comes from!

The process is really very close to improvisation when you’re an actor. You start by imagining yourself being that person, in such a situation, what would you think, how would you react, and then things start to escape you and you find yourself saying or doing things you wouldn’t have thought about. Only, as an actress you’re not often given the chance to play the part of a man, while as a writer, you get to play all the characters in your head!

SS: This is your first novel translated into English. Did that affect your writing or editing process?

NA: Well, I didn’t know when I was writing it in French that it would get translated so obviously the original version was not affected by it. Now my U.S. publisher Judith Gurewich thought the novel was a bit too long, and she asked me to cut out three chapters, which were, in the French version, the ones told from the point of view of the husband. I trusted her and I accepted. And then I worked closely with Adriana Hunter on the translation to make sure the irony, the kind of sardonic, matter-of-fact, no-bullshit tone of Juliette’s voice came across. Irony is the hardest thing to translate.

SS: What themes were you looking to explore in Couple Mechanics?

NA: I have been trying to explore all forms of violence between men and women, some of them carefully hidden under the words “love” or “passion.” It goes from physical violence to emotional blackmail, but it also raises the issue of imposed paternities, which is to me a gigantic abuse of power on the part of the women. Another theme of the novel is the opposition between two ideas of feminism: the one defended by Simone de Beauvoir nearly 50 years ago and another, newer one, denounced by Elisabeth Badinter in an essay that deeply influenced me called, “Dead End Feminism.” And finally, of course, there is the old conflict between family and passion, the question of knowing if a long-lasting love can exist.

SS: Do you think the novel would have been different if it were set in the U.S. instead of France? Do you believe the countries have different views on love?

NA: I really don‘t think so. I know American people have this fantasy about France and the French that everybody there is having affairs and that it’s okay and that nobody cares, but this is absolutely not true! Being betrayed by someone you love is a devastating experience for everybody, French women included—otherwise I wouldn’t have been able to write 300 pages about it!

SS: Your novel has garnered rave reviews from the likes of The Economist, Kirkus Reviews, and Library Journal. What’s that experience been like and what’s next for you?

NA: It’s just wonderful. I love the United States and I have spent a lot of time there over the years, I have friends there and that makes me incredibly happy that they’re finally able to read my books!

What’s next? I am working on my next novel, obviously. And I also have several screenwriting projects, among which is the adaptation of Couple Mechanics as a French television series. And, why not, a feature film in English if I can get a U.S. producer interested!

SS: What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

NA: Read a lot. Read, read, read. And then try to write something you would enjoy reading.

To learn more about Nelly Alard, visit her Other Press author page.

The Writer's Bone Interviews Archive

Romancing the Light: 12 Questions With Author Andrea Dunlop

Andrea Dunlop

By Lindsey Wojcik

“I can’t believe you’re leaving Manhattan.”

The opening line to Andrea Dunlop’s debut novel Losing the Light immediately pulled me in. The thought of leaving New York City is something I grapple with daily, yet the line also had me yearning to discover an exotic place far from Manhattan.

As 30-year-old Brooke Thompson prepares to leave Manhattan to move upstate with her fiancé, she runs into a man she once obsessed over, French photographer Alex de Persaud, at a party. Though Alex does not seem to remember the time they spent together in France while Brooke was an exchange student, Brooke accepts an invitation to meet him for a date the following week.

The meeting sends Brooke into a tailspin, and she’s flooded with memories she hoped to forget about her year in France—including an affair with a professor, her close friendship with fellow American exchange student Sophie, and the impact that Alex had on her a decade prior. Dunlop also takes readers on a journey to the picturesque city of Nantes, and she sprinkles the French language into dialogue throughout. (I had the opportunity to read the book in its natural habitat on a recent trip to Paris and hoped it would improve my French. Il a aidé un peu.)

Dunlop, a Seattle-based writer and the social media and marketing director of Girl Friday Productions, recently took some time to answer questions about her first novel, her cure for wanderlust, and what notable figures would be invited to her dream dinner party.

Lindsey Wojcik: Did you grow up wanting to become a writer, or was that something that grew organically over time?

Andrea Dunlop: I always wanted to be a writer. My mom loves to tell people about finding little scraps of paper with dialogue written on them all over the room when I was a kid. It’s always been wrapped up in my identity.

LW: Who were your early influences?

AD: I was lucky in that my parents read to us a lot when we were kids. Some of the first books I remember being captivated by were those in C.S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia. The idea of having a portal to an alternate world really captured me: probably because I always felt a bit like that with my own imagination. I discovered Sandra Cisneros in high school, and her work is so beautiful and vivid, I’ll never forget reading The House on Mango Street for the first time. In college, I studied with the novelist Pat Geary, who became my mentor and friend. Her work is stunning and impossible to put into a genre: magical realism would be the closest. Not every great writer is a great teacher, but she definitely has that distinction.

LW: What's your writing process like? Do you outline, just dive in, listen to music, etc.?

AD: I write in the morning when I first wake up—after coffee, of course. I usually have a general idea of where the story is going, but I’m often surprised by what comes up as I’m working. That’s the most gratifying part of the process for me: that I learn more and more about my characters as I write them.

LW: What inspired you to write Losing the Light?

AD: I started writing an early draft 13 years ago when I was still in college. I had just returned from a semester in France, and it was an utterly transformative experience—not in the way it is for my characters, I would hasten to add. To be truly out of your element in that way, to see with your own eyes how differently people in other countries live, that was something that stuck with me in a big way. What’s interesting is that when I started the book, I was the age of my characters in the flashbacks, and when I finished it I was roughly the age Brooke is when she’s looking back, so I felt all the nostalgia that she’s feeling about those memories.

LW: How much of yourself—and the people you have daily interactions with—did you put into your main characters in the novel? How do you develop your characters in general?

AD: My characters often have an initial real-life inspiration, but the fun part is that they grow to very much have a life of their own on the page. I usually draw inspiration from people I have brief interactions with, rather than those I know well. It’s fraught to write about someone you know well, obviously, and also, if you’re too close to someone, your imagination has no space to fill in all the gaps. A huge theme of Losing the Light is the way in which you become infatuated with people when you’re young, and therefore completely misunderstand their true nature and intentions. I often feel that first flush of infatuation with characters, and then grow to know them on a deeper level as I go.

LW: What were some of the themes you wanted to tackle in the novel?

AD: One of the major themes is the sense of possibility that you feel when you’re on the cusp of adulthood. It’s really a coming of age novel in that way: that opening of the mind and heart when you leave your home for the very first time, especially traveling abroad, that was something that was really life-changing for me. The female friendship angle is also very strong, the way in which when you’re that age, friendships feel like the most important thing, and yet they’re often complicated and even destructive. Those friendships are almost romantic in their intensity—even if they never become sexual—you feel like you can’t live without the person and you just want to be with them all the time. And everyone is still figuring out who they are, so the breakups are often even more dramatic than whatever romantic splits you have. It’s so different than when you’re in your thirties and your best friends are people you’ve known for a decade through marriages, kids, what have you.

LW: The book’s opening line “I can’t believe you’re leaving Manhattan” really struck a chord with me as a New Yorker, and it's something all New Yorkers can relate to—the unbearable idea of leaving the city. You left New York for other adventures. What was the hardest part about leaving? What do you miss the most?

AD: To be honest, it wasn’t so hard when I left because I was really ready for a change. But if you’d asked me two years earlier if I’d ever leave, I would have said “Leave New York? Blasphemy!” New York is a pretty magical place, and for me it was the perfect place to spend my twenties. There is the sense in New York that anything can happen at any time, that there are life-changing opportunities around every corner. It’s thrilling and exhausting in equal measure. I worked for Doubleday when I was in New York, which taught me so much that has put me in good stead as a publishing professional and an author. I wouldn’t trade those years for anything, but nor would I ever be tempted to move back. Certainly it was glamorous and exciting and that sense of possibility was wonderful. Everyone you met was doing something fascinating; I feel like I met plenty of difficult people, but never boring ones. I miss that. And also—no disrespect to Seattle, which has many fine restaurants—but I miss the food! And the pizza? Get out of here.

LW: What's your cure for wanderlust?

AD: Well, travel if possible. Even going somewhere not terribly far-flung for a quick weekend can give you a new perspective and remind you how vast and wonderful the world is. But if not, books! I think that traveling via book is something all readers can relate to. The variety of perspectives available to you in books is mind-blowing. One of my favorite book-travels in the past few years was reading the stunning Ghana Must Go by Taiye Selasi. It was so vivid and transporting; I don’t know that I will ever get the chance to visit Lagos or Accra, but with this book, I was given a meaningful glimpse at what life in those places is like. I really hope that American publishing will move in the direction of incorporating more diverse voices in the coming years, including translations, otherwise it’s such a missed opportunity for us all to see outside our own experiences (and for underrepresented voices, see to see their own experiences reflected). Buzzfeed is doing some truly impressive work in this area, including their fellowship program. More of that please.

LW: How has your role as the social media and marketing director for Girl Friday Productions helped your writing career?

AD: My work with GFP has given me an incredible skill set for marketing my own work. The job of being an author, and a businessperson with a product to sell, is quite different from the job of being a writer—an artist who needs to create. I think my career in publishing has given me a unique appreciation for the way in which those two roles must co-exist and also remain separate. My work has given me a lot of skills in terms of promoting my work, but perhaps even more helpfully, it’s given me the ability to take a step back and not take things super personally. Once the book was finished, I put my marketing hat on. Many writers are way out of their comfort zone having to promote their own work, but the way I see it, this is my job. I worked really hard to get a book published, and I want it to reach as many readers as possible; I don’t think that’s anything to feel embarrassed by! Many other people also worked very hard on my book—my agent, editor, publicists, etc.—and so anything I can do to promote the book is for them too.

LW: Now that you have your first novel under your belt, what’s next for you?

AD: Working on another book, of course. My new novel is about a woman who discovers that she has wealthy cousins she never knew about when she meets them at her mother’s funeral. She joins them in New York two years later and much drama ensues. It’s about how you think you know your family members, but actually your very closeness to them can obscure some truly disturbing things about their nature. I’m also very excited to be writing about New York!

LW: What’s your advice for up-and-coming writers of all kinds?

AD: Figure out what your goals are, and then work towards them accordingly. Maybe you just want to write for yourself and a small audience, that’s absolutely valid. There are plenty of university presses and small presses that do amazing work for a small handful of titles each year. Maybe you want to be a best-selling author someday, that’s awesome, but recognize how much work that will take, far above and beyond writing a great book, which is always step one. I also feel that it’s really important to support the community on which we all depend: i.e. other writers, booksellers, etc. Always be reading new books by your fellow authors, talk about them on social media, review them on places like Goodreads and Amazon, and come see them when they visit your town. If you want support from the community, it starts with you.

LW: Can you please share a random fact about yourself?

AD: I’m obsessed with exercise guru Shaun T. I do one of his Insanity workouts almost every morning. The workouts are great, and he just seems like such a lovely positive person. I think he is a good force in the world. Do you ever do that game where you imagine your fantasy dinner party? Mine is Shaun T, Cheryl Strayed, Elizabeth Gilbert, and Michelle Obama. There could be more, but I’d want to keep it intimate. We’d eat something healthy but there would also be plenty of wine.

To learn more about Andrea Dunlop, visit her official website, like her Facebook page, or follow her on Twitter @Andrea_Dunlop.

The Writer's Bone Interviews Archive

Sweet Hilarity: A Conversation With Author Julia Claiborne Johnson

Julia Claiborne Johnson

By Daniel Ford

The clock read 1 a.m. Only fifty pages remained in Julia Claiborne Johnson’s mesmerizing debut Be Frank With Me. My coffee had worn out and I was tempted to put my bookmark back to work.

The novel simply wouldn’t allow it. The story would break your heart one moment and then force it to take flight the next. Structured around a reclusive author, an insecure assistant, and an eccentric and immensely lovable 9-year-old, Be Frank With Me will move anyone who has ever been labeled “different” or “outsider.” I can’t remember the last time I had time to actually re-read a novel, but I have no doubt that I’ll pick this tale up again in the near future.

Julia Claiborne Johnson was kind enough to talk to me about her secret weapon during the writing process and what inspired the wonderful characters in Be Frank With Me.

Daniel Ford: Did you grow up wanting to become a writer or did the desire to write grow organically over time?

Julia Claiborne Johnson: I was always a writer. My mother had a typewriter that she must have used in college, in the late 1940s or early 1950s. It was my main source of amusement when I was a kid. My hands must have been unusually strong for a grade-schooler because I wrote a lot of stories about my dolls on it. Sadly, lost to the sands of time.

For me, writing always came naturally. It was something I was born with, like having the naturally blonde straight hair like Alice, the narrator of my novel. I assumed that writing came easily to everybody else, too, and took it for granted. My English teacher told me when I was a freshman in high school that I’d be a writer, and I can remember thinking at the time, “Yes, yes, but will I ever be popular?” Not a chance of that for me then. But some of the girls who were the social superstars of my high school just came to my reading in Nashville, so I guess it all evens out in the end. If you’re willing to wait 40 years.

DF: Who were some of your early influences?

JCJ: The novels of P. G. Wodehouse were the first serious books I loved. By “serious” I mean “books adults read” because honestly, those novels were the antithesis of serious. For some reason they had a lot of Wodehouse in the Shelbyville Public Library. They made me snort with laughter in middle school. In high school, I went for the usual stuff, like Hemingway and Fitzgerald. More Fitzgerald because there was such an ache about him, but he was so charming and could be funny, too. Also, Fitzgerald was married to a Southern girl and I was a Southern girl. When I was fifteen I loved reading Zelda, that bio of his wife by Nancy Mitford. Not that I wanted to be Zelda. Being Zelda was interesting, but way too exhausting. In college I loved Flannery O’Connor and Walker Percy and Robert Penn Warren. William Styron.

Beyond all that, I had a father who told amazing stories. On long car trips with my family, we children would hang over the back of the front seat, listening spellbound, while my mother drove. Which was good, because my father cared more about holding his audience than staying on his side of the road. Also, he was one of those “Never let the truth get in the way of a good story” guys. That’s an excellent tradition to be raised in if you’re going to grow up to write fiction.

DF: What’s your writing process like? Do you outline, listen to music, etc.?

JCJ: I often work wearing those earmuffs the guys who use flashlights to direct airplanes into their parking spaces wear. Noise distracts me. So does music. I unplug the house phone and turn the ringer off on my cell. Chain myself to my chair. My husband started calling me “Iron Ass,” which, it seems, was Nixon’s nickname when he was in law school because he could sit in the library studying longer than his more charming and talented fellow students. So that’s my great skill—what I lack in genius I make up with in determination.

Can I tell you about what turned out to be my real secret weapon? Naps. I tried to work a 30-minute one into each work day if I could because my unconscious was great at untangling knotty story threads while I slept.

DF: I gladly lost a night of sleep finishing your utterly charming debut Be Frank With Me. What inspired this tale?

JCJ: Good, somebody else losing sleep from all the writing I did. That seems fair, since I spent so many years writing after I put my children to bed and walked around in a fog most days because of that. Really, though, that’s great to hear. I love finding books I can’t put down. I think that’s the highest compliment you can give a novel.

Here’s what got me started: When my daughter was in middle-school, she read To Kill a Mockingbird, a book I hadn’t read since I was about thirteen. So I decided to reread it then. This time around, as the middle-aged parent of children in public school in the 21st century, it struck me that Boo Radley might have fallen somewhere on the autism spectrum. And that, moreover, characters like Boo had always existed in fiction; in the old days there were no handy label to slap on them to explain their behavior. My very next thought was, “Well, it’s a lot easier to write Boo Radley than is to raise him.” And with minutes, my whole story rolled itself out, because it was a story I wanted to read. An eccentric kid; his mother, who’d written that character and was now raising him; and a girl in her twenties who thought she knew everything about raising children because she’d never really been tested by a difficult child. I made a conscious choice not to say that Frank was on the spectrum. As helpful as labels can be, I thought labeling Frank would limit him, so I didn’t. I was writing a work of fiction about individuals in a difficult situation, not a psychology textbook.

DF: You introduce readers to one of the most memorable characters I’ve read in a long time. Frank, a 9-year-old boy who enjoys dressing and acting like classic movie stars, is the beating heart of the novel and is an absolute joy to read even when he’s forcing other characters to their breaking point. How did you get into his mindset in order to develop his character? How much of yourself ended up in Frank, as well as the rest of your characters?

JCJ: I think I’m more Mimi and Alice than Frank. My daughter, in fact, says Alice is “nice me” and Mimi is “mean me.” And that, moreover, she gets Mimi while her brother gets Alice. Sigh.

When I was thinking about how Frank was going to be, I decided early on that I didn’t want him to be some meek kid in the back row of his fourth grade class, dressed in Garanimals and doing quadratic equations while the rest of the class drilled on state capitals. I wanted people to be able to look at him and know right away that he was different. In my twenties, I’d worked as a writer in fashion magazines in New York City. Up until then, I was only familiar with the kind of academic achievement that gets rewarded in school. The good students got ahead, and the bad students got jobs at the chicken plant. But once I was working in magazines, I came up against visual genius for the first time. The fashion people were brilliant and amazing to look at, and, alas, often inarticulate. So what? You could see them coming from a mile away, and you knew right away that they were singular. It wasn’t like I people who passed me on the street saw me and thought, “Look at that girl. She can write.” So I decided to make Frank visually splendid, because honestly, there isn’t enough fabulousness in the world. Unfortunately, being fabulous at Frank’s age is the equivalent of wearing a bulls-eye for bullies on your chest to school every day.

As for the whole Old Hollywood business, I’ve lived in it for the past 20 years. My house used to belong to Oscar Hammerstein’s son, and the club at the end of my block is the one Groucho Marx wouldn’t belong to if it wanted him as a member. I can walk to Paramount studios, which is where Fred and Ginger filmed their movies. I love all that stuff. Can you blame me for putting it in my book when I’m surrounded by it every day?

DF: The novel explores themes dealing with not only the relationship children have with their parents and their peers, but also issues that creative people, particularly writers, grapple with on a daily basis. Did you set out to tackle those themes or did you discover them as you were telling this story?

JCJ: This novel was about outsiders from the get-go. I was the chubby, awkward Teacher’s Pet who got picked last for every team on the playground and never got invited to parties. My husband is a comedy writer, and listen, most comedy writers aren’t prom kings, either. When you’re a kid, it can be hard to grasp that the things that make you a success as an adult are the very things that make you a loser when you’re young. Would knowing that make things any less hard when you’re in grade school? Probably not. It’s hard to be different. That’s why Mimi has the list of all the people who never finished college or high school or grade school in her bedside table drawer. She just needed to keep reassuring herself that what was unique about Frank would make him a success in the world, if it didn’t kill him first the way it killed her brother.

DF: Your writing style in the novel is so witty and well honed. How did you develop your voice? Are you able to slip into it during the writing process or is it something you find while you’re editing?

JCJ: I don’t pretend to be a brilliant prose stylist. If you’d met me, you’d know that Alice’s voice is more or less my voice. I talk the way she does. My husband always says that we’re raising our children to think it’s more important to be funny than to be good. Uh oh. He may be right about that. Just please don’t ask me if my husband helped me write my jokes. I’m always shocked when people ask me that. Surely they don’t mean to suggest that a woman can’t be funny on her own? I will say this, though: Living with a guy who is hilarious as my husband is has upped my game. Our house is a wit-friendly environment. We fell in love with each other because we crack each other up. And have, for the past twenty-five years.

DF: When you finished your first draft, did you know you had something good, or did you have to go through multiple rounds of edits to realize you had something you felt comfortable taking to readers?

JCJ: I think I felt that way after I wrote the first chapter I put to paper. It’s Chapter 8, the one where Alice spends the night alone with Frank for the first time. In it you’ll find every mother’s fears of all the ways your kid could find to kill himself and others if you look away for even a minute. I had assumed I’d be a great mother, but I was completely unprepared that level of constant vigilance. It was exhausting. After I’d finished writing Chapter 8, I thought, “Hey, this could really be something.” That’s all that got me through the thousands of pages I wrote to get to the three hundred or so I ended up with. The belief that, if I could just get it right, people would want to read it. Why? Because I never got bored with the story myself.

Here’s what was the most thrilling part of this whole experience for me. When I finished that first draft late one night after three years of sweating over it, I googled the name of my favorite author’s agent. (Bel Canto by Ann Patchett is my favorite book.) I found the agent’s name and sent an email to her fancy agency in New York. I didn’t think I’d hear from her for months, if ever. When I woke up, the agent had written me back to ask to see my manuscript. She took me on as a client a week later. I still had two years of revisions ahead of me, but I had an agent. I still can’t believe how lucky I was. The part I’d always assumed would be the hardest turned out to be the easiest of everything.

DF: Now that you have your first novel under your belt, what’s next for you?

JCJ: I hope I will start writing my next book June or thereabouts. I have a couple of ideas that seem solid to me. I’ve spent the past few months reconnecting with friends and re-familiarizing myself with the world outside my office. Once I got going on it, I was so determined to finish Be Frank With Me that I wouldn’t socialize or answer the phone or emails or do anything I didn’t have to do to keep my family together. I’m so glad it worked out in the end because if it hadn’t it would have been so depressing to miss out on so much fun for so many years.

DF: What’s your advice to aspiring authors?

JCJ: Don’t talk about the book you’re going to write. Write it.

DF: Can you please name one random fact about yourself?

JCJ: I grew up on a farm so I’ll be handy to have around when the zombies come. I know how to milk a cow and ride a horse and fish and string barbed wire. I don’t have the hand-eye coordination for a bow and arrow. I wish I did. I flunked archery at camp, despite wanting so desperately be good at it. Which is probably why I gave Frank that bow and arrow.

To learn more about Julia Claiborne Johnson, like her Facebook page or follow her on Twitter @JuliaClaiborneJ.

Full Interviews Archive

A Conversation With High Dive Author Jonathan Lee

Photo credit: Tanja Kernweiss

By Adam Vitcavage

Jonathan Lee is no stranger to the literary world. He is a senior editor at Catapult and a contributing editor to Guernica. Lee has previously published two books in Europe, but the British writer has just published his first novel in America. High Dive has already received advance praise ahead of its March release and was selected to be apart of Barnes & Noble’s Discover Great New Writers program.

His smartly written story about the 1984 assassination attempt of the British Prime Minister juggles multiple characters and threads in an inmate way. Fellow authors have proclaimed Lee’s pacing and dialogue are exceptional, which is obvious from the very beginning.

I chatted with Lee via email as he embarks on a U.S. book tour about where this book came from, his writing process, and the literary world he’s a part of.

Adam Vitcavage: Why this event? Did you already have interest in the bombing when you thought of the idea? Or did you seek an event out for the book?

Jonathan Lee: For me a book always comes out of a specific image or fact or moment. I’ve never been able to write well about broad ideas—I’m more of a micro thinker, and, therefore, a micro writer. I’m interested in small details and moments and hope that by paying an almost absurd amount of attention to those micro moments—finding the right word when a character is fusing electrical components together, or finding the right image to capture the feel of the air in a swimming pool—larger patterns will emerge on their own. So my idea for High Dive wasn’t “I must write about the conflict in Northern Ireland.” It was that I’d seen The Grand Hotel on various childhood visits to Brighton, was maybe struck by the grandeur of it—so different from the three-bedroom, viewless terraced house I grew up in—and eventually heard the small details: that this long-delay device had been planted in the hotel under the bath in room 629, and had exploded 26 days later. That 26 days, and that bath, and that room number... These were the kinds of micro things that fascinated me. I began at some point to wonder what life was like in the hotel during that 26 days of highly charged unawareness, if that makes sense. And also what life was like for the men who had planted the bomb and were back in Belfast, waiting to see its effects on a television screen.

AV: What sort of research had to go into this?

JL: Lots of reading of IRA memoirs, many of them self-published. Lots of hanging around in hotels. Lots of reading about hospitality, as a trade—books written by people who managed hotels, and also brilliantly absurd 1980s books aimed at telling travelers on how to get the most out of their hotel experience. I tried to avoid reading too many books about the time and instead focused on books written in the time—1984 and the years before it—as well as newspaper accounts from the relevant months. Those kinds of contemporaneous records have none of the lethal objectivity of hindsight, do they? I wanted to avoid deep-freezing my novel with hindsight. If a character said or thought something about Thatcher, I wanted the hot mess of what they thought or said to be there on the page. I wanted everything to be in the moment—very partial and open to revision.

AV: How did writing this book differ from other projects? How was it similar?

JL: High Dive is my third novel, and somehow the writing doesn’t get easier with each new book. The good news is it doesn’t get harder, either. I guess I worry a little less about things like plot than I used to do. I’m keener now to let the entire plot, the sequence of events—and I do like there to be events; I like my novels to offer a compelling narrative—to just emerge from the personalities, the natural decisions, of my characters. With High Dive, more than with earlier projects, I wanted to be very focused on day-to-day lives. I wanted character to be plot, and character to be language, and character to be structure. The other thing that gets very slightly easier the more books you write, I find, is that you get better at getting characters in and out of rooms, and using section breaks and chapter breaks to your advantage—leaning into the white space when you need to. There was a time when I’d send my characters on all these costly 5,000-word taxi rides. Now, more often, I just have them thinking about going to X or Y’s house, and then turning up. I can’t tell you what a relief it is to no longer be describing those taxi rides.

AV: Building off of that: how did you decide to weave these particular stories together?

JL: I just started writing a few pages from the perspectives of six or seven possible characters, and the three who are center stage in the published book seemed to be the ones that intrigued me most. I didn’t have a specific structural idea at the start, save for the fact that I wanted the story to look at things at least two ways—to have an Irish republican perspective as well as a protestant English one—and I wanted it to move back and forth in time in a manner I still think of, perhaps rather grandly, as tidal. As the book progressed it also seemed to me to make sense to pull the rope of the narrative very gradually tighter—to have the three main threads, the three characters’ stories, get closer to each other as the ending came near. So by page 300 or so you have these very short sections—sometimes just a paragraph—before the next character has his or her close third person section. The characters’ fates and thoughts become more intertwined as we approach the explosion. There’s a sort of structural empathy, maybe—purely structural.

AV: How would you describe your writer process for novels? How intricate are you outlines? For instance: do they include white boards of each chapter?

JL: No, I’m not much of a planner. I just start writing and see what comes. Worse, I’m a hypocrite about it, because when I teach students on occasional residential courses or workshop weekends, I preach the importance of planning. It’s because I know my own methods lead to so much wastage—tens of thousands of words needing to be cut away, and several novels abandoned midway through.

AV: A lot of aspiring writers don’t really get the process of selling a book. Can you take us through how this became your first American release?

JL: Well, that’s a long story. It took me a long time to find the right U.S. editor—one who could fall in love with weird novels set in England, which are the kinds of books I seem to write. For my first two books I was lucky to have publishers in Poland and Taiwan and all sorts of places, but not America. But I think sometimes aspiring writers worry about trying to please everyone, as I used to do, when in fact you just have to please one person. Publication is a process of matchmaking, I think. It is more intimate than people think, and it requires patience. At each stage before publication, you only need one person to really love your work. One agent’s assistant—the one who looks through the slush pile. Then one agent. Then one editor. In Diana Miller at Knopf, I happened to find the perfect U.S. editor, and in Jason Arthur at William Heinemann in the U.K. I’ve had for many years an essential relationship too—he was the first editor who ever saw any potential in my work. Then there’s also this issue of community-building, and that too is intimate. I sometimes get messages from writers starting out that contain a line like “I only read the classics.” That’s an infuriating thing to say. You have to support the system you want to be part of. If you want to write contemporary fiction, read some contemporary fiction. If you want to be an author reading your work at a bookstore one day, go see authors reading at bookstores today. Maybe even set up your own reading series. Build the community. Go to the library and read a story in Tin House before you think of submitting to Tin House. You don’t want to be published everywhere, and you don’t want to be edited by everyone—you just want to find the one or two key people who love the sentences you love.

AV: When you’re giving talks, how different is each appearance? Or is there a script where you always want to hit certain points for discussion? If so, what are those points?

JL: A script! If only. It depends who the audience is. I feel like a lot of readers that I’m meeting on the High Dive book tour at the moment are also aspiring writers. So I try and bear that in mind and not get too caught up in talking about this or that moment in the book when what they might be looking for is more general encouragement, or to hear me or another author talk about craft. When I went to readings in my early twenties in London, I was often attending more out of a fascination with process than through obsession with a particular book. It’s the same reason I compulsively read Paris Review interviews back then. They got into the nitty-gritty of process, the staples and paper and handwriting. And I remember writers like David Mitchell being really kind when I queued up to get a copy of an early book of his signed many years ago. He took one look at me and said, “So you write as well, then?” Not “want to write.” Not “hope to write.” He didn’t condescend. There must have been a certain desperation in my eye, and he was incredibly kind—he knew he was part of a community.

AV: You interview a lot of authors. What’s your approach to those conversations? What do you choose to focus on?