By Daniel Ford

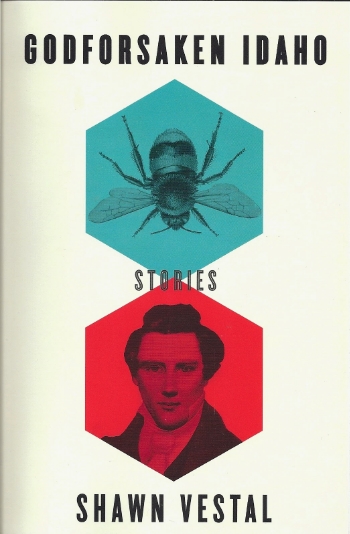

It was the title of Marie-Helene Bertino’s book that caught my eye. 2 A.M. at the Cat’s Pajamas is not something you encounter on every walk through your neighborhood Barnes & Noble. The novel’s lime green back cover did the rest of the work, pulling me in like a tractor beam.

Degenerate music club. Broken characters. Dark Philly streets. I was 10 pages deep before I remembered I had to go back to work. I was all in.

The best thing I can say about Bertino’s book (for now, I’ll have an official recommendation coming in October) is that it is a constant surprise. Sentences hit you with left hooks after you’re punch drunk from right hand jabs, multiple storylines dance nimbly to the accompanying music, and Bertino writes with a confidence typically reserved for seasoned masters. I’m less than 25 pages from the end and am reading a page at a time because I don’t want it to end.

Bertino talked to me recently about her early influences, her writing process, and the inspiration behind 2 A.M. at the Cat’s Pajamas.

Daniel Ford: When did you decide you wanted to be a writer?

Marie-Helene Bertino: I decided when I was 4 years old, and I decide again, every day.

DF: Who were some of your influences?

MHB: My brothers were my first influences. They are older than me, and I saw them writing when I was a little girl. There was such mystery and delight surrounding the activity of them scribbling into their copybooks, and I wanted in on that. In grade school, the stories of Lloyd Alexander and Madeleine L’Engle and the fantasy genre in general were huge influences. In high school and college, poets were my biggest influence. After college, I went to London to study Shakespeare. Later, irreverent surrealists like Etgar Keret, Aimee Bender, Amy Hempel, Jim Shepard, and Raymond Carver guided my first forays into fiction.

DF: What is your writing process like? Do you listen to music? Outline?

MHB: I don’t normally listen to music or outline, unless I need a jolt back into the story. When I’m “composing” a new piece if you will (will you?), it needs to be quiet in the palace. Nothing louder than my cat padding across the floor. When I’m writing non-fiction or revising, I listen to NPR all day. I do a fine impression of Lakshmi Singh if I may say so (may I?), and groove without realizing to the Brian Lehr Show theme song.

DF: You teach at NYU, The Center for Fiction, The Sackett Street Workshops, and the Emerging Writer’s Workshop for One Story. How have all of these organizations influenced your writing?

MHB: My students at NYU are brilliant and energetic, willing to fearlessly try new things. I leave class inspired and chuckling a lot. This semester I began teaching in the low-residency program at IAIA (Indian American Institute of the Arts), based in Santa Fe. IAIA’s mission is “to empower creativity and leadership in Native arts and cultures through higher education, lifelong learning, and outreach.” It is a new M.F.A. program built out of deeply ingrained tradition and feeling, and I am already learning so much from the other faculty members and students. In the workshops at IAIA, CFF, Sackett, and One Story the students are sometimes several years past college age. They normally work day jobs in unrelated fields before coming to class each night. I have a very real understanding of the sacrifices they make to be there, and their determination and talent stokes my own desire to keep writing.

DF: Your first published work was a collection of short stories titled, Safe as Houses. What drew you to short stories originally and why did you make the decision to switch to the novel format?

MHB: I like the canvas of short stories, that they are in essence a magic trick. Other magic stories compelled me to write my own. “Why Don’t You Dance” from Raymond Carver was the first one I remember giving me that gut punch—only not the story. It was produced as a short film at The Tribeca Film Festival years ago, and I liked the film so much I sought out the author. The last lines of that story still hold great alchemy for me. While I was writing the stories in Safe as Houses, I switched back and forth to 2 A.M. at The Cat’s Pajamas. The scope of the latter’s story overflowed a story container. It took a long time for it to teach me how to write it.

DF: How long did it take you to complete your first novel 2 A.M. at the Cat’s Pajamas?

MHB: That’s a tricky question to answer, because I didn’t work on it for hours every day for 12 years, though all in all, from first word to publishing, it was that long. During that time I wrote a children’s book, another novel, my short story collection, in addition to becoming the person I had to be to write the novel. So, that’s a loose figure, at best.

DF: Did you know you had something good when you finished?

MHB: I knew I had something that was exactly what I wanted to say.

DF: How did the idea for the story originate?

MHB: I was having a string of late nights in Philadelphia, hanging with friends and hearing music. Then I moved away and became homesick. I wanted to write something that felt the way I felt when I was in the city with these friends. But it took a long time to figure out how to do it. It’s not a one to one ratio. And, music is deceptively tricky to write about.

DF: How much of yourself—and the people you have daily interactions with—did you put into your main characters? How do you develop your characters in general?

MHB: I am lucky that I was raised by a woman who has an uncanny knack for understanding a broad variety of people. My mom worked for forty years for people living with severe mental disabilities. She taught me to be a people person, in the true sense of that word. This includes the world-weariness that only people who truly love other people encounter. In any case, I’ve always been interested in other people’s experiences. I’ve held two jobs that required me to interview people—in one case, musicians, in the other, people living with TBI, but I’ve been informally interviewing people my whole life.

DF: 2 A.M. at the Cat’s Pajamas has gotten great reviews. What has that experience been like and what’s one memorable moment that will stick with you?

MHB: I hesitate to admit this, but I don’t read reviews. I hesitate because sometimes this seems to invite people to tell me what they think about me not reading reviews. But I decided long ago to put to route anything that is bad for my writing. And, I can’t see how an overly positive or overly negative review could help my writing in any way. I also decided never to walk in anyone’s shadow. If I fail, if I succeed, at least I lived as I believe. No, wait. That last part was Whitney Houston.

DF: What’s next for Marie-Helene Bertino following the success of your first novel?

MHB: Oh, you know. Writing, writing, writing. I’m puttering right now, on a book and stories, the way a gardener putters in her garden. I’m doing a lot of readings—which is a lot of fun. I’d like to do more readings, visit schools, talk to emerging writers. I’d like to visit Arthur Avenue in the Bronx for the first time. And India. I’d also like to figure out how to make a flower crown, and teach my dog to turn around while standing on his hind legs. I don’t know about that last one. He just doesn’t seem interested.

DF: What advice would you give writers just starting out?

MHB: I have so much advice for new writers, but here is one specific tidbit: Ask yourself, what am I avoiding in my writing? And, force yourself to write it. Maybe it’s dialogue, sex scenes, descriptive scenes, scenes where more than two people are speaking, dialogue beats, whatever have you. Force yourself to write two pages of it. Again, and again. Work to refine that skill like you would a weak muscle. And keep doing that every so often, no matter what level you reach.

DF: Can you please name one random fact about yourself?

MHB: Besides the Lakshmi Singh thing? I am preternaturally adept at parallel parking.

To learn more about Marie-Helene Bertino, visit her official website, like her Facebook page, or follow her on Twitter @mhbertino.