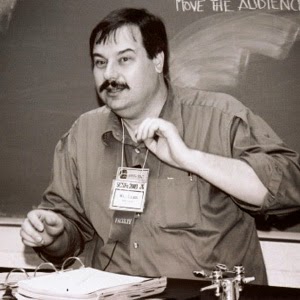

Matthew Abeler (Photos courtesy of Matthew Abeler)

By Rachel Tyner

We’ve all been there. Seemingly enjoying a nice conversation with a friend when you suddenly realize you’ve been talking to yourself for past 10 minutes while your friend has been texting, Instagram-ing, or Tinder-ing.

Matthew Abeler, a student at the University of Northwestern of St. Paul with a keen sense for observation, noticed this as well. He began thinking about how technology affects our relationships and the types of messages we send to our friends and families when we choose to use our phones instead of engaging in conversation. So, “Pass the Salt” was created.

After seeing the “Pass the Salt” video in my newsfeed I knew I wanted to get in contact with its creator. After some quick Google action, I came across a “Pass the Salt” Facebook page. I sent a quick message , not knowing who would be on the other end, or if someone would even respond. Luckily, Matthew came back with some insightful answers.

I look forward to seeing what he is going to come up next. Be sure to check out his video, his YouTube channel, and put down the phones and pass the salt!

Rachel Tyner: Give us a little bit of your own background. Who you are, what first got you interested in film, what factors contributed to turning an initial interest into a passion, etc.?

Matthew Abeler: I was born left-handed and right-brained. I grew up in rural Upsala, MN where my parents run a Christian Bible Camp (Camp Lebanon). I spent a lot of time outdoors playing sports, fishing, hiking, and climbing trees—doing anything to appease my craving for adventure. My imagination ran wild and drove my parents and older siblings crazy, but they encouraged it even further by reading an endless amount of stories to me before bed. Most of these were from the Bible, and I became fascinated with larger than life storytelling.

I was initially interested in drawing, music, and writing long before film. I enjoyed trying to copy reality in pencil sketches, particularly the features and emotion in faces. I rebelled in my piano lessons by ignoring the songs I was supposed to practice and instead writing my own. To this day I still regret not being able to sight-read well because of this “distraction.”

I never landed on one particular skill, which is what led me to film. Film is an everything art. I realized everything I created in drawing, music, and writing could belong together in one form. I began by making home videos with my older brother, and they eventually turned into larger collaborative efforts like “Pass the Salt.”

RT: Was this video inspired by a particular dinner? What sparked you to comment on this aspect of social interactions?

MA: Surprisingly, “Pass The Salt” wasn’t sparked by a traditional family dinner. It was my interactions with college students at the University of Northwestern of St. Paul (where I currently attend) during lunch and dinner that inspired it. I noticed how “normal” it was for an entire group to have their phones out at the tables, sometimes oblivious to each other. I wondered how a parent would deal with the problem. That initial quandary led to a personal commitment not to use my phone at mealtimes even in the collegiate setting. Later, I gave a speech on the subject of “Media Obesity: Technology and Relationships” for one of my classes, and decided a comedic video could engage interest in the topic. My speech professor denied the request to use an original video, but I enjoyed the script so much I decided to make the film anyway.

RT: You describe "Pass the Salt" as a "video short about technology and relationships.” I find that description really interesting, as opposed to a "video short about texting at the table.” Is this a topic that has been discussed often in class, with friends, family etc.? How do you think technology has affected our relationships?

MA: When I was researching the topic for my speech, I discovered that there were greater problems swimming beneath the surface of little things like “texting at the table.” The problem is more about value than it is about cellphones. If I am having a deep conversation with my parents, and I whip out my phone I am implicitly telling them “I value the conversations with my friends on the phone more than the conversation I’m having with you.” This can cut deep, even if its status quo behavior.

No matter what I’m doing, if something causes me to turn a deaf ear to my close friends, I hurt not only them, but also my ability to maintain long lasting, tight-knit relationships.

Behind the scenes of "Pass the Salt."

RT: I first saw this video on Facebook when my uncle posted it. The next day, I was telling my boyfriend about it when he exclaimed, "Oh yeah I saw that! Hilarious." Obviously, with more than two million views, this is reaching a wide demographic. Almost everyone can relate to this, but is it geared toward a particular audience?

MA: I love hearing stories like that. My mom has a friend who hosts exchange students in her home, and one of the woman’s previous students from Sweden discovered the video and shared it with her. The woman was shocked when she recognized my mom in the video.

Most watching the video are of the ages of 18 to 35 and 65+. Although I’d like to credit myself for knowing the audience well before creating the video, I didn't really have a particular demographic in mind other than my speech class. I can, however, explain a possible reason for the wide ranging demographic.

The average human peaks at about 150 relationships in a given community, but because of a desire to be valued by many, we’re often convinced we need more relationships to be content and/or significant.

Not surprisingly, the average number of Facebook friends per person shows that the 18 to 24 age demographic is most guilty of this tendency, and the demographic 65+ is least guilty.

- Age 65+: 102 Friends

- Age 35 to 54: 250 Friends

- Age 25 to 43: 360 Friends

- Age 18 to 24: 649 Friends

Because the problem is not mere technology or media, but our confusion with more relationships meaning better relationships, the age categories on separate ends of the totem pole relate to the video the best, even though it doesn’t explicitly deal with this subject.

RT: This video was uploaded a year ago. When did you first start to see a dramatic increase in shares and views? Do you think it correlates to anything?

MA: Five weeks ago it jumped from 3,000 views to 30,000 in a single day. This seems to have occurred as a result of a Women’s Retreat guest at Camp Lebanon who asked my mom (who also starred in the short film) if she could use the film in an online course she was teaching. From there it snowballed into more than 2,000,000 views and Ashton Kutcher even shared it on his Facebook page.

RT: Where did that typewriter come from and what is "Dad" (is that really your dad?) typing during the video?

MA: I borrowed it from a friend our school’s theater department whose house is full of vintage “stuff.” My dad (yes, he is my real father) was having trouble operating the typewriter because the keys were sticking. Most of the typing was a nonsensical ink mess, but I later found fragments of a poem about pumpkins.

RT: While you do not make an appearance in “Pass the Salt,” you have in some of your other videos. Do you have a preference—behind the scenes or in front of the camera?

MA: I enjoy both. The exercise of acting for camera helps me direct the performances of actors. However, I rarely act in a production I am directing. Collaboration is hands down my favorite aspect of film production. Immense joy comes from inviting the talents of others onto a production and I’m finally coming to terms with the fact I can’t do everything myself.

RT: In 10 years, what will the title on your business card read?

MA: “Children’s Storyteller Specialist”

RT: Name a random fact about yourself (other than a love for mom's lemon meringue pie).

MA: I have only one dimple, but I show it a lot.