By Sean Tuohy

Offerman Woodshop, located in Los Angeles and helmed by comedian and “Parks and Recreation” star Nick Offerman, has been described as “kick-ass” and is filled with extremely talented and skilled artists. With the help of RH Lee, I was lucky enough to learn more about what it takes to design an original piece of art from a slab of wood.

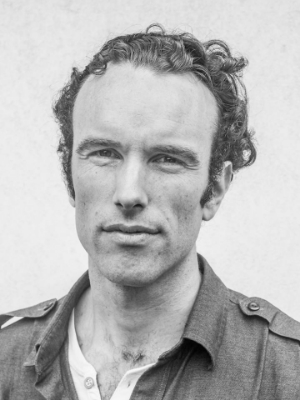

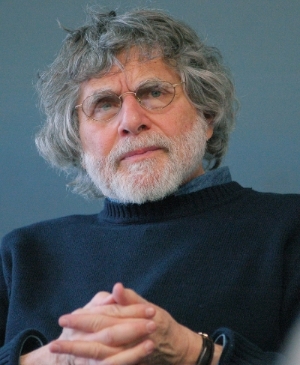

Matthew Micucci

Matthew Micucci (All photos courtesy of Drift Journal and Offerman Woodshop)

ST: How did you get into woodworking?

MM: When I lived in New York City I was lucky enough to get a job at the Public Theater as a set builder. I had no deep desire to build but the job was a welcome change after working in the service industry. I quickly discovered that there is a unique bond that forms among your co-workers when you are working physically with each other on a project. It was unlike any other job I've had (and I've had a lot!). You become a family. When I moved to Los Angeles a few years later I knew I needed to find a gig that was similar in order to find my “people” in an otherwise very strange town. So, long story short I am a woodworker simply because I wanted to live a life with people that have a physical job, work with their hands, and create things simply because I knew they'd be nice folks. My theory turned out to be true.

ST: Is woodworking a hobby or passion for you?

MM: It's not a hobby. It's my way of paying rent. It's my main social group. It's my reason for enjoying life in Los Angeles. When I'm doing it I'm certain it's not my passion. It's a job. But when I go home for the evening and I'm sitting on the couch sipping a whiskey getting excited about tomorrow's part of the project and looking forward to being with the crew again I wonder...Maybe it is a passion? Nah, can't be.

ST: What was the first item you made out of wood?

MM: The first thing I made was a birdhouse when I was little with my Uncle Pete. We eventually blew it up with fire crackers years later because a hornet’s nest started taking it over. That's how we handled things in the crazy 1990s.

ST: Do you have any pre-woodworking rituals?

MM: Coffee.

ST: What advice would you give to a first-time woodworker?

MM: Measure twice cut once. Measure three times...Just have Nick cut it.

ST: Is there a piece you have made that you are most proud of?

MM: I'm very proud of a few pieces. One that comes to mind is the Zeus Wagon Wheel, which is a seven-foot diameter circular table made from recycled wood with a mahogany Lazy Susan. We all worked as a team on that and it turned out amazing. The client was extremely gracious and excited about it, which is always icing on the cake. However, I think I'm most proud of maintaining and taking care of the shop. When the machines are clean and running smooth, the air filters are clear, materials are well stocked, and the shop floor is organized I feel a strong sense of pride. It's the little things.

ST: What is your dream item to make out of wood?

MM: Currently a dream would be to make a dining table for myself. It's hard to find the time and energy to make things for yourself when you're at the shop most days of the week working on other projects.

Thomas Wilhoit

Thomas Wilhoit

ST: How did you get into woodworking?

TW: I came to woodworking by dabbling in many related fields. I grew up on a farm and spent a bit of time logging, putting up fences, and doing barn repair and other construction projects. I was an actor, and through that got involved with set construction, having an abundance of experience using tools. Finally, in college I did some sculpture and wood, naturally, became my favorite medium. Eventually, when I moved to Los Angeles, I stumbled upon OWS, and it was unlike anything I had encountered in the city (or have since), so I decided I had better become a woodworker for real and lock that shit down. To have an opportunity to work with such an amazing collection of people is a rarity.

ST: Is woodworking a hobby or passion for you?

TW: Hm, well, those seem awfully similar to me, and I don’t think either is entirely accurate. Presumably most people are passionate about their hobbies, since they pursue them for pleasure. Woodworking is my occupation, so it certainly isn’t a hobby, by the very nature of the word. I like to think that I’m passionate about it, but there are also plenty of moments when I get frustrated flattening a slab or during a complicated glue up and just want to go collapse into a comfortable chair and drink a beer. Most people’s experience of woodworking is limited to the realm of the hobby, so it’s natural that they assume full time woodworking is just like getting to work on your hobby all week, but like any job, it has highs and lows. So, if you mean passion in a slightly archaic sense, then yes, I feel a range of strong emotions about woodworking.

ST: What was the first item you made out of wood?

TW: That’s digging deep—I used to make myself toys out of wood. I know that makes it sound like I grew up on a tenant farm in the 1870s, but I guess I was always dissatisfied with the toys that you could buy at the store. So, I would make all kinds of stuff, like wooden knives and swords, castles, boats, that sort of thing.

ST: Do you have any pre-woodworking rituals?

TW: No rituals, per se, but I like to start the day at the shop with a glass of water and some beef jerky. And, of course, I like to get pretty handsy with the wood while I plan a project.

ST: What advice would you give to a first-time woodworker?

TW: Don’t wear gloves when using tools; it’s a serious safety risk. Just accept that splinters are part of the job and toughen up.

Also, be prepared for frustrations and failures, and be flexible—you have to work with the wood, you can't just impose your will upon it.

ST: Is there a piece you have made that you are most proud of?

TW: We did a massive round table out of glulam for a client, and it was completely beyond our shop’s capabilities. They just don’t make much equipment for dealing with those dimensions. Because of that, we had to think on our feet and do a lot of creative problem solving, and that’s what I love most about woodworking. And, it turned out pretty gorgeous in the end.

ST: What is your dream item to make out of wood?

TW: I don’t have a “dream project,” but it’s hard to beat working with a beautiful slab. Frankly, if my goal was simply to make things, I wouldn’t choose wood as my medium—it has a whole host of complicating factors that make it a real pain in the ass. I’m a woodworker because I enjoy working with wood, dealing with the natural quirks that give it such unique beauty. It might sound a little cheesy, but I try and think less about some conceptual form or item that I want to produce and more about the potential in each piece of wood. So, I definitely don’t have a dream item, but I can point you toward a number of dream slabs that I want to work with.

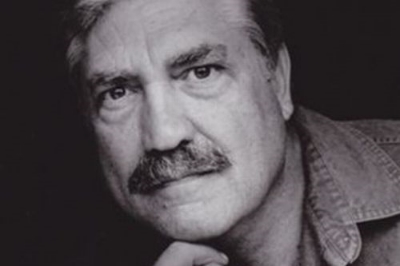

Nick Offerman

Nick Offerman

ST: Can you explain what “traditional joinery and sustainable slab rescue” is?

NO: “Traditional joinery:” Missionary position? The knee bone connected to the thigh bone, knuckling under or above, having one’s nose in or out of joint, etc.? Or you may be referring to methods of joining the discrete implements in a piece of wooden furniture to one another without fasteners such as nails or screws. For example, the four sides of a Shaker blanket chest are traditionally joined to one another by cleverly interlocking dovetail joints at the corners. Traditional “post-and-beam” or “timber-frame” construction heavily utilizes the mortise-and-tenon joint, which can be exemplified by making a “vessel” (mortise) with one hand, and inserting the index finger (tenon) of the other hand into it. Repeating this traditional action brings us full circle to the missionary position.

“Sustainable Slab Rescue” refers to the practice of re-using local trees that have been felled by storms, nature, or construction needs, by milling them into table slabs and other lumber. Many urban trees become landfill fodder, or at best, firewood, while woodworkers and homebuilders rely upon lumber companies to harvest forest products from distant locations and then expend even more fossil fuels to transport those two-by-fours to our lumberyards. By setting up a local milling service, we can give our local trees a valuable second life as furniture and home decor, while burning a hell of a lot less diesel shipping in Douglas Fir timbers from British Columbia.

ST: How did you get into woodworking?

NO: I grew up in a farming family in Minooka, Ill., learning to use tools for carpentry and mechanic work from a young age. I framed houses for a summer, then did some roofing before learning to build professional theatre scenery. I made a good half of my living in Chicago building scenery by day and acting in plays at night, which further honed my competence in working with tools in a shop. Once I moved to Los Angeles in 1997, I began to construct decks and cabins in peoples’ yards, which included teaching myself post-and-beam construction, particularly inspired by the local works of the architects Greene and Greene. One day I was chopping out a large mortise, when I realized that traditional furniture utilized the exact same joinery just on a smaller scale, and I was bewitched. A friend gave me Fine Woodworking Magazine and I devoured it, a matriculation that continues to this day.

ST: Is woodworking a hobby or passion for you?

NO: This question confuses me. It seems to presuppose that one may not be passionate about one’s hobby. To my way of thinking, a hobby can be precisely described as a productive diversion in one’s life about which said person is passionate. As in, “Fred’s probably out in the garage building one of his popsicle-stick ‘Star Wars’ vehicles. It’s his passion.” If you mean to ask if woodworking is a hobby as opposed to something more, say a vocation, then I would have to say it is a vocation. It is a discipline. A true woodworker is more than a hobbyist, if one considers “hobby” to represent a diversionary activity like repairing antique pocket-watches, or photographing and cataloging local bird species. Woodworking, I think it’s safe to say, requires a greater commitment than any mere hobby. What I mean is that woodworking is a craft that, once begun, continues to hold the woodworker in its grip, rewarding her or him with a progressive accumulation of knowledge throughout a lifetime of craft. If I were to simply enjoy building birdhouses in my spare time, with no interest in heightening my skills or tool knowledge, then I would consider myself a hobbyist who uses woodworking to make my charming product, but I would demur at being referred to as a “woodworker.”

On the other hand, if one is besotted with the tutelage of all the great woodworkers who have come before and left for us their instruction in books and periodicals, or simply in their works in homes and museums, then I would consider woodworking an obsession and a vocation. This is the case with me. I began, as many do, by building a box. Then I built a box with a lid. I chose each new project based upon some new joinery technique so that my knowledge and skills would progress equally apace. Then I built a table, then more tables. I built a small four-foot lapstrake rowboat as a cradle. I built a canoe. I built another canoe. Then I built a ukulele. I am itching to get back to my shop to build several more ukuleles so I may then graduate to acoustic guitars. Beyond that, I may build more boats or instruments—the mandolin and the violin are both calling my name from afar. In a few months it looks like I will get to take a Boston workshop in building a traditional Windsor chair, and that has me bristling with excitement, as the techniques involved are not yet ones that I wield in my personal bag of tricks, and in woodworking, every new technique becomes part of the invaluable body of knowledge that allows the woodworker to solve each unique problem as it arises.

ST: What was the first item you made out of wood?

NO: In truth, a crappy tree house down by the creek with my pal Steve Rapcan. My father and I also built a small barn at our house before I began framing houses. The first item I made once I got turned on to woodworking was a jewelry box for my wife, who was my girlfriend at the time.

ST: Do you have any pre-woodworking rituals?

NO: No specific rituals per se, although consuming a bounty of bacon and eggs doesn’t hurt. Woodworking requires a clear head and perspicacity when it comes to safety around the tools and materials.

ST: What advice would you give to a first-time woodworker?

NO: Plan to make mistakes. Practice joinery and get to be comfortable with your tools on scrap wood before you ruin some expensive walnut.

ST: Is there a piece you have made that you are most proud of?

NO: To date, I am most proud of my first canoe, Huckleberry, built with the techniques I learned from Ted Moores in his book CanoeCraft, and his plans from Bear Mountain Boats. That noble vessel, my main ride, also served as the canoe of Ron Swanson on my television show “Parks and Recreation” until the series finale in which he paddled into the sunset in my second canoe, Lucky Boy.

ST: What is your dream item to make out of wood?

NO: The next one. At the moment it’s more ukuleles.

Josh Salsbury

Josh Salsbury

ST: How did you get into woodworking?

JS: I always liked building things when I was growing up. As a kid, I played with Lego all day long. In college, I ended up studying music at the Eastman School of Music and UCLA and then had a brief professional trombone career. After feeling unsatisfied with the freelance Los Angeles music life, I enrolled in a woodworking class at Cerritos College on a whim. I was instantly hooked and dove into fine furniture making. I enjoy woodworking because like music, it still has a creative element but the end result is something that is physically tangible.

ST: What was the first item you made out of wood?

JS: My first memory of making something was taking a bunch of nails and hammering them into a scrap of wood in the shape of a happy face when I was a little kid. My father set me up in the backyard with blocks of wood, nails and a hammer and said, “Have fun!”

ST: Do you have any pre-woodworking rituals?

JS: I don’t have any rituals per se, but whenever I walk up to a tool, especially a power tool that wants to eat me, I make sure I am aware of my surroundings and that I’m in a proper state of mind to operate it. Things can go wrong in an instant if you allow your mind to wander! I always respect the tools.

ST: What advice would you give to a first-time woodworker?

JS: I would advise new woodworkers to enroll in a class. If you are in Southern California, the program at Cerritos College has semester-long courses. Or if you just want to get a taste of woodworking, check out Off the Saw in Downtown Los Angeles. Taking a class is a good way to learn how to safely use the tools and meet other like-minded creative people.

ST: Is there a piece you have made that you are most proud of?

JS: I recently completed a coffee table made out of a Bastogne walnut slab with an ebonized eastern walnut base. The slab was one of the more unique pieces of wood that I have had the opportunity to work on and had a lot of interesting figured grain. The overall design of the table was simple, but it allowed the beauty of the wood to be the focal point of the piece.

Bastogne Walnut Coffee Table

RH Lee

RH Lee

ST: How did you get into woodworking?

RL: There was an after school program at my elementary school called Kids' Carpentry. That's where I learned to employ hand tools and soft pine to make pretty much anything I wanted. My beloved grandpa Sam was an amateur woodworker (in addition to being amateur hunter, beekeeper, photographer, chemist, and psychedelics enthusiast). He was paralyzed by a stroke when I was little and so from a young age he asked me to be his woodworking proxy. I like to think he would have been proud to see me now.

ST: What was the first item you made out of wood?

RL: Hard to remember the exact chronology, though many of my “rustic” early works are still kicking around my parent's house in Berkeley.

A cutting board they still use even though its just a piece of one-by-eight pine board that I cut with a handsaw in 1984, the skateboards I built and road down to splinters, a small chair I built in our basement, and various wooden toy walky-talkies and high tech spaceship consoles with bottle caps for buttons.

ST: Do you have any pre-woodworking rituals?

RL: Unless I am making a delivery or a lumber run, I always ride my bicycle to the shop in the morning. From my house I take the Los Angeles river bike path and small neighborhood streets. I find that my best creative ideas and problem solving happens in this quiet pre-work ride between the river and the interstate.

ST: What advice would you give to a first time wood worker?

RL: Start by making things for yourself and your loved ones, and continue to do so even as you start to find paying work. When you make your own furniture, you get to figure out your own standards—you can let go of perfection and accuracy and let simple accidents guide you to your aesthetic. Then as you live with the piece, you learn what works and what doesn't over time. Since we strive to build furniture that will last for generations, the knowledge of the functionality and temporality of your work is invaluable to informing design.

ST: Is there a piece you have made that you are most proud of?

RL: I worked closely with the Outdoor Gallery at the Exploratorium Museum of Science, Art and Human Perception developing a new set of outdoor exhibits for public interaction. I'm particularly proud of the mobile museums that I built with friend and engineer Jesse Marsh. Together we engineered and crafted a mini interactive museum console mounted on a Dutch tricycle chassis. Museum educators did public science outreach by riding the museum on wheels out on the Embarcadero.

ST: What is your dream item to make out of wood?

RL: I've always wanted to build a mobile tiny house—something simple but fully tricked out with low-tech multipurpose modular components. Every square inch would be a completely economical and functional use of space.

To learn more about Offerman Woodshop, visit its official website or like its Facebook page.