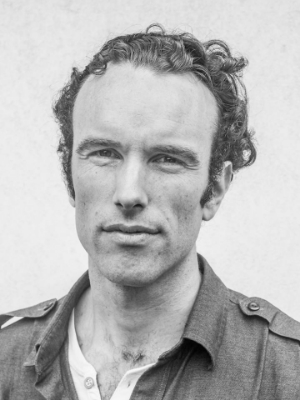

Elliot Ackerman

By Dave Pezza

I wrote in a recent Bruce, Bourbon, and Books that Eliot Ackerman’s debut novel Green on Blue “perfectly balances on the line of critiquing American ideals in a Middle Eastern society and the illuminating the struggle of the honest Afghan men and women who try only to survive in this contested land they call home.”

Ackerman recently answered some of my questions about why he wanted to be a writer and how his involvement in Afghanistan shaped the characters and events in Green on Blue.

Dave Pezza: Just wanted to say we’re passing our copy of Green on Blue around Writer’s Bone HQ, and it’s really a solid read. It’s not often you get a “war” novel that fights hard to not be preachy or jingoistic. Was this something you purposefully sought after or was it simply a product of your involvement in the conflict as a soldier during your five tours of duty?

Elliot Ackerman: Thank you, I am glad the novel resonates with the gang at Writer’s Bone. I am trying to picture your HQ. My mind projects bookcases filled with scotch, or maybe books…I am also getting a strong mahogany vibe. As to your question, the writing I admire is never didactic but generous. It shows the story instead of telling it, giving the reader room to inhabit the narrative. When I served in Afghanistan, it was exclusively as an advisor to Afghan troops. I wanted to show the war as I think they saw it. I wanted a western reader to stand in Afghan shoes.

DP: The relationship of your characters, especially between Mr. Jack (the American CIA operative) and Commander Sabir (leader of the Afghan Special Lashkar unit) reads so real, so full of dishonesty and symbiotic necessity. Based on your work as a combat advisor for an Afghan commando unit, are these relationships as strained and convoluted as dramatized in your novel?

EA: The novel is most certainly not my experience, but it is informed by my understanding of the Afghan war. My ambition with the novel was to try to render that war in miniature, an incredibly complex conflict that’s been ongoing since 1979. I wanted to show the economies which surround war, the manner in which war elevates its participants—making them commanders, contractors, informants—and show how once those structures are in place war becomes a force which feeds on itself, often being fought for every reason but its end.

DP: The Afghan population, their poverty, and their struggle to simply make a living struck me the hardest throughout Green on Blue. Has this lifestyle changed at all since American involvement or after it for that matter?

EA: It’s difficult to say whether or not life is better for Afghans before or after the American led invasion of 2001. The only fact of which I am certain is that Afghan life is worse since war came there in 1979. In the novel I wanted to show how that life, one filled with the privation and violence, brings conventional, western notions of right and wrong into question. Very little is black and white when life is lived in those extremes, morality becomes relative to circumstance.

DP: Has writing been a passion of yours? When did you know you wanted to be a writer, and how did that affect your decision, if at all, to join the military?

EA: I always knew I wanted to write. My mother is a novelist so I grew up around it. I studied literature and history at university, taking creative writing classes with Andre Dubus III at Tufts. I also always knew I wanted to join the military. I came into the service as a Marine infantryman in 2003 which, with the beginning of the Iraq War, was an interesting time to be joining. I spent eight years going in and out of Iraq and Afghanistan. I didn’t have the space to write much during this time, let alone to publish. It was only after deciding that chapter in my life was over that I was able to turn to writing full time.

DP: It seems Green on Blue has been getting some good attention, and rightfully so! Did you think that Americans would take so kindly to a war novel told from the Afghan perspective?

EA: I’m not sure what I expected. Writing a novel is a very intimate experience. You have this close relationship with the work for such time, showing it to only a few trusted people along the way. Then on a certain date it is published and out in the world—readers are engaging with it. And, if you are lucky, some of your readers will share the intimacy you had with the work, its characters and the story. If another feels that emotion, if it’s been transferred from author to reader than the book is a success. This type of emotional transference is the goal of all art, and where it has happened with Green on Blue I feel enormous satisfaction.

DP: What’s next? You’re based out of Istanbul writing about the ongoing Syrian Civil War. Can we expect an equally compelling account of that very complex conflict?

EA: In addition to the reportage I file from the region, I’ve also been working on a novel which is set on the Turkish-Syrian border. It is a love story, and won’t say much more than that.

DP: Any tips for writers and veterans who are trying to get their own work and experiences published?

EA: My father used to tell me that you don’t find a vocation by imagining the best aspects of a job and then deciding you’d like to do it—so you don’t decide to be a musician by imagining thunderous applause at Carnegie Hall, or to be an entrepreneur by imagining your billion dollar IPO in Silicon Valley. He used to say you find your vocation by imagining the worst aspects of a job, asking yourself if you still feel compelled to embark on that type of work, and then, only if you answered in the affirmative, you might have found your vocation. There are parts of writing which are wonderful—the work when it’s going well, publishing, friendships with other writers, interacting with readers—and there are parts which are miserable—the work when it’s going poorly, rejection, indifference from readers. If you see no other way than to write, then write. But success and failure will come hand in hand, so have an appetite for your failures.

DP: Can you give us one random fact about yourself?

EA: How about two truths and a lie? Maybe you can publish the lie in very tiny print at the bottom of this interview:

a) I once ran with the bulls alongside Dennis Rodman in Spain.

b) I was once lost at sea off the coast of Mexico.

c) I collect rare butterflies.

To learn more about Elliot Ackerman, visit his official website or follow him on Twitter @elliotackerman.

Answer: c is the lie.