Theresa Rebeck (Photo credit: Monique Carboni

By Daniel Ford

Theresa Rebeck has written everything from award-winning Broadway plays to hit television shows (Admit it, you had “Smash” on your DVR).

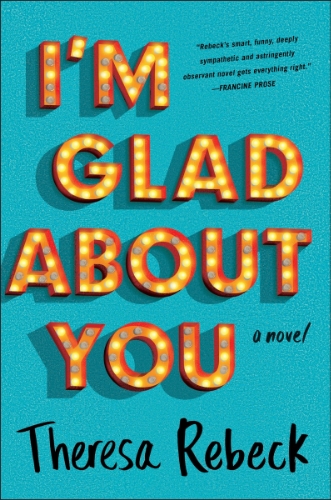

Rebeck’s recently published novel, I’m Glad About You, features star-crossed lovers, Midwestern sensibilities, New York City Millennial drama, quippy dialogue, and plenty of dark, twisted angst.

The author/screenwriter/playwright (when does the woman sleep!) graciously took some time away from her production schedule to answer my questions about her writing career, what inspired I’m Glad About You, and what aspiring authors need to do to succeed.

DF: Did you grow up knowing you were going to be a writer, or is it a passion that grew over time?

Theresa Rebeck: I thought I was going to be a writer when I was about 3 years old. That’s not to say that I fully believed it. Even when I was young and a dreamer, it felt like a very bold choice. And certainly everyone I knew in Cincinnati thought I was somewhat insane to think that someday I might be a writer.

There were a lot of other dreams in there. I dreamed of being a chemist, or a mathematician, or a doctor. I’m good at math and chemistry, improbably, so my pragmatic Midwestern roots argued in that direction. Eventually reality caught up with me, at which point that first dream looked more like what it was—determination.

DF: You’ve written critically acclaimed Broadway plays and hit television shows. Were there any disciplines you learned that you were able to transfer to writing I’m Glad About You?

TR: The novel remains a mystery and a challenge to me. One of the things you learn in the theatre and in TV is that you just have to keep working until you finish it, and then you have to finish it again. There’s a lot of forward motion, always. And that turned out to be a very useful tool to have in my toolkit when facing the complexities that arise in the writing of a novel.

DF: When you sit down at your computer to write, what’s your process like? Do you listen to music? Outline? Was your writing process for I’m Glad About You any different than your screenwriting process?

TR: I think in screenwriting and in television writing, there’s generally too much outlining. So when I’m working in fiction, I try to keep things looser. I have a general idea of where I’m going, but I don’t want to have too much settled on before I’m actually writing. I feel like the writing reveals a lot of surprises and deeper secrets when you haven’t made too many decisions ahead of time. That’s not to say you should just go blindly into something, I don’t believe that. I try to hold some tension between what I know is going to happen and what I don’t know.

DF: What inspired I’m Glad About You?

TR: I’m from Cincinnati and I live in New York. I used to think that at some point, those two aspects of my personal story were going to make more sense to each other. But, they didn’t. And I became aware over time that this is a real problem in our country—I feel like no one knows how to talk to each other anymore, and I wondered what that would look like if I had a pair of lovers who ended up in that situation.

DF: Kyle and Alison could have easily been caricatures we’ve seen in past novels, movies, and television shows, but you ground them in reality and give them honest-to-god issues to wrestle with. How did you go about developing these two, and how much of yourself landed in each one?

TR: Developing characters is something that comes to me over time. I did know when I started working on the novel that I was going to have Kyle stay in one place, and that Alison, by contrast, was someone who would rise, in visibility, in the wider world. Kyle’s journey was always going to be more and more interior, more and more isolated, more and more centered on this lonely quest for a spirituality that would often elude him. His innate decency is not enough, finally, for Kyle: He truly wants to be a good man. But what does that mean, to the soul?

Alison’s journey is more like Sister Carrie’s, in a way: as she rises as an actress, she becomes more and more of an object. But Alison surprised me. She refused to accept that destiny. She never saw herself as an object, so she never fell prey internally to what was happening to her externally.

DF: As a playwright/screenwriter by trade, did you start with the dialogue and fill in the prose or did you have the story in mind and craft the dialogue organically?

TR: I don’t do anything like that—start with the dialogue and then fill in the prose. I start at the beginning, and when I get to the end, I stop. And when I rewrite, sometimes I add things in, sometimes I take things out. Only one time in my life did I write a story in pieces, different scenes that weren’t connected, that were connected only later. If there’s anyone out there who writes the dialogue first and then fills in the prose, I’d like to talk to them. That sounds kind of interesting to me.

DF: How long did it take you to write I’m Glad About You? Did you settle on the novel’s structure during the writing or editing process?

TR: It took me a really long time—it felt like a really long time. It took me about six years. I came up with the structure during the editing process. Because there are two sides in the story, I did have a lot of material I ended up cutting. It wasn’t clear to me from the onset how the two strands of the story would sit next to each other. So that was something that emerged with greater clarity as I worked on later drafts.

DF: I’m Glad About You has garnered rave reviews from critics and readers alike. What’s next for you?

TR: Right now I’m in pre-production for a movie I wrote starring Anjelica Huston, Bill Pullman, and David Morse. I’m directing it as well. And then I have some other ideas that are starting to emerge. I’m so compelled by fiction right now but it’s a lot of work, it requires a lot of space and silence and I haven’t had that lately.

DF: What’s your advice for aspiring writers?

TR: Learn how to finish drafts. So many people get caught up in the process and don’t ever see the point where it says, “The End.” So even if you have to push through sections that aren’t working—I’m not saying force it, though sometimes you do have to force it—finish a draft. Also, I think writing a lot is a good thing. Like practicing scales on a piano. The more you write, the better you get...hopefully. Don’t be precious: learn how to cut. Learn how to edit.

DF: Can you please name one random fact about yourself?

TR: I have the best collection on Earth of tiny stone bears. I also collect Peruvian retablos. I guess that’s two facts but seriously the little bears are great and so are the retablos.

To learn more about Theresa Rebeck, visit her official website or follow her on Twitter @TheresaRebeck.